Today the field is overgrown with leafy weeds that crawl over fences and onto the surrounding sidewalk. The swing sets have no swings, the basketball courts no hoops. Weeds sprout from asphalt, carving the parking lot into myriad continents.

"This was the front entrance," says Kenya Gray, a 29-year-old computer analyst who lives in the Mt. Pleasant neighborhood surrounding the school. "Now look what it is: rubble."

Once the pride of the neighborhood at Signet Avenue and East 123rd Street, Lafayette, after eight years of abandonment, has turned into a deadweight on the community's spirits and property values. In that time, pastors from two churches purchased rights to the school, each promising renovations that would bolster the area. Yet the property continues to crumble.

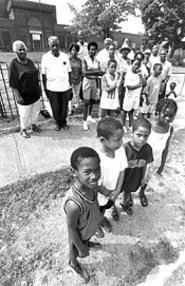

Mt. Pleasant is one of Cleveland's most venerable black neighborhoods, dating back to the early 1900s. It's said that, in 1893, a contractor who was unable to pay wages compensated black workers with vacant lots here. By 1975, the neighborhood was 95 percent black. Residents kept their lawns watered and their gardens brimming with flowers.

Lafayette Elementary was the community's crown jewel. Built around 1920, the sprawling, one-story brick building is a prime example of Classical Revival architecture, employing motifs from Roman and Renaissance buildings. But by 1995, the school had crumbled like an ancient artifact. Rain dripped through the ceiling. Electrical outlets were so deteriorated that plugging in cords brought the risk of shock. A federal court ordered the school closed.

The decline of Lafayette mirrored that of the neighborhood. Mt. Pleasant lost one-quarter of its population from 1970 to 1990 as middle-income families fled in droves. Broken-down properties and storefront vacancies drove down the median house value to just $37,450 in 1990.

Residents say the dilapidated school became a crime magnet. Sara Jackson, an elderly woman with bottle-red hair, sees drug deals from her porch and children playing on the school's roof. Grandparents say they are afraid to let children out because they could be snatched from the lot's four acres of tangled brush. And the school has become a dumping ground for old tires. Classical Revival has evolved into a classic eyesore.

"Would you want to open your blinds every morning and see something like that?" asks Jackson.

Residents want to know why the school was left to lapse for so many years. "It's the first thing we look at in the morning and the last thing at night," says Lou Owens, a 52-year-old former steelworker. "We're tired. We want something done."

The school district auctioned off Lafayette for $40,000 in 1996. The sole bidder was Reverend Arthur Rucker of the Highway and Hedges Outreach Ministry, who later earned a reputation for buying property on God's advice ("Religious Eviction," May 2, 2002).

Rucker says he planned to turn Lafayette into a charter school, but the district never transferred the deed. Worse, nobody secured the school against vandals. "People pulled semi trucks up to there and stole all the oak wood that was in the building, stole the copper piping, stole the flush [toilets] out of the school," he says. (The district professes not to know what happened, since the school closed before CEO Barbara Byrd-Bennett's administration.)

A year after the auction, Rucker sold his purchase rights to Reverend Larry Harris of the Mt. Olive Baptist Church for $20,000; Harris would still have to pay the school district for the property. In June 1997, he agreed to buy Lafayette from the district for $30,000; the deal was finally completed in January 2001.

It seemed a promising event, since Harris knew a bit about schools and buildings. Mayor Michael White appointed him to a panel to choose a new school board in 1998. He also served on a commission to study how to improve district buildings. But the reverend apparently hasn't applied what he learned to his own property. (Harris did not respond to repeated requests for interviews.)

Residents say they've had similar luck trying to wring information from the pastor. When Owens asked to see a feasibility study completed July 15, the church agreed, but has yet to produce a copy. And one church member says Harris lectured her for making noise about the abandoned school. "My pastor tried to say something to me about it, that I was with the wrong group, that I was against the church," says the woman, who asked not to be named. "I'm not against the church. I'm for the community. That really hurt me."

None of which has helped Mt. Olive's relations in the neighborhood. Councilman Zachary Reed recently admonished the church, saying, "The people who live in that community want to know what's going on, and to keep them in the dark is not helping."

Inez Killingsworth, who serves on the church's development board, deflects blame toward the school district. "I understand the complaints that the community has, and the community had those complaints with the board of education," she says. "The board of education should not have allowed it to happen like that. But it did."

Mt. Olive says it plans to demolish Lafayette and build in its place a 2,000-seat church, which is projected to take two years. The idea rankles residents. "This is a historical landmark to this community," says Owens. "We want it preserved and we want it restored. We do not want demolition."

The Cleveland Restoration Society agrees. It added Lafayette to its list of endangered historic properties. "[The residents] live in a neighborhood that is -- I don't want to offend anybody, but it's not an up-and-coming neighborhood," says spokeswoman Julie Langan. "This is, for them, one of their best buildings."

But Mt. Olive may not have much choice. The feasibility study says retrofitting the structure would be too time consuming and costly. Lafayette is said to be riddled with asbestos; the study put the cost of abatement during demolition at $250,000.

Whatever the church decides to do, it will have to act fast or it could find itself lighter in the collection plate. Before Mt. Olive bought Lafayette, a city inspector cited it for numerous building code violations. Housing Court Judge Raymond Pianca has ordered Mt. Olive to fix the problems within a year or pay a $50,000 fine.

And that's not the only financial threat the church is facing because of Reverend Harris's real estate deals. Harris also bought from Reverend Rucker the only house that shares the block with Lafayette. Now Rucker is suing Harris for breach of contract, claiming he never paid the $29,189 purchase price nor took over the outstanding $41,323 mortgage.

The church has cleaned up the tires and cut down the tallest weeds at Lafayette, but the heavy lifting will take longer. Residents like Sigler, who once watched children play baseball at Lafayette, wonder if they'll live long enough to see the property's rebirth. "This neighborhood was so beautiful," she says. "So beautiful."