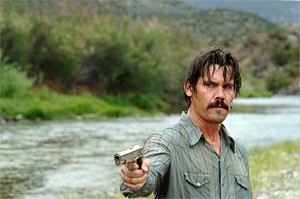

"Hold still." The first time we hear these two words in the Coen Brothers' new film, it's Vietnam vet Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), perched on a West Texas ridge and whispering to an antelope he spies through the sight of his rifle. Later, "hold still" is the phrase used by steely assassin Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), as he talks to a terrified motorist to whose skull Chigurh has pressed a cattle gun. By that point, not very far into the film, we already know that anyone who stands in Chigurh's way is in immediate peril. There are regular movie psychos, and then there are those, like Anton Chigurh, who lower the temperature in the theater whenever they appear onscreen.

"Hold still" is also what the Coen Brothers seem to be saying to the audience throughout No Country for Old Men, which is the most measured and classical film of their 23-year career — and maybe the best. There are echoes of earlier Coen films here — in the Texas setting (Blood Simple) and the idea of simple, small-town folk caught up in criminal business (Fargo). But unlike the eccentrics at the center of most of their movies, the characters in No Country for Old Men are stoic, solitary figures who feel most at home in desolate landscapes. We see and hear things as they do — subtle sounds in the atmosphere and terrain, like the faint jangling of keys in an abandoned vehicle resting in a desert clearing, where bad men have recently done bad business. It's to this grisly scene — a drug deal gone awry — that Chigurh journeys in search of a briefcase piled high with cash (two million 1980 dollars). But Moss, the hunter, has been there first and has left just enough of a scent for Chigurh to track.

Based on the novel by Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men is a cleverly triangulated cat-and-mouse pursuit in which Chigurh stays a few short paces behind Moss, while the sheriff, Ed Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), closes in on them both. If Chigurh is the movie's phantom bogeyman, Bell is its moral compass, albeit one with its needle pointing straight to hell. A onetime believer in the forces of law and order, he has been worn down by what he sees on his beat and reads in the newspapers. Whether the good old days Bell pines for ever existed is another matter entirely, one that No Country for Old Men doesn't endeavor to resolve.

The movie recalls vintage film noir, and as such it is destined to be studied in film schools for generations to come. Students will spend evenings engrossed in the threatening beauty of cinematographer Roger Deakins' O'Keeffe-like images as well as what is surely the most pulse-raising motel-room scene since Marion Crane took her fateful shower in Psycho. There isn't a moment here that feels false, less than fully considered, or outside of the Coens' control. Nor does the movie ever feel studied and inert in the way movies so carefully planned and executed sometimes can. And then there is Javier Bardem, whose Chigurh is so fully realized psychologically and physically that his every gesture bristles with creepy fascination.

It's easy to imagine how the Coens, whose Achilles heel has always been their tendency toward smug irony and caricature, might have turned McCarthy's Texans into simple western archetypes: the amoral criminal, the righteous peacekeeper, and the naive but basically good-hearted rube who's in over his head. Instead, they've made a film in which words like "hero" and "villain" carry less and less weight as the plot unfolds. Like McCarthy, the Coens are less interested in who gets away with the loot than in the primal forces that urge the characters on. "They slaughter cattle a lot different these days," a weary Bell sighs late in the film. But they slaughter them nonetheless, and in the end, everyone in No Country for Old Men is both hunter and hunted, members of some endangered species trying to forestall their extinction. Even Anton Chigurh, it turns out, bleeds when wounded.