There is a certain regularity to Mayor Frank Jackson's schedule. On Monday mornings he has a legislative review with Valarie McCall, the city's chief of government and international affairs, and then, usually, a school district briefing in the afternoon. He meets with his cabinet and the board of control on Wednesdays. On Thursdays he receives a public safety briefing. Fridays, there's a meeting with his COO, his chief of staff, and the chief of regional development, along with a briefing from the law director.

There are monthly meetings with county executive Armond Budish, quarterly meetings with the Port of Cleveland, and regular sit-downs with the federal-appointed monitor and city-appointed coordinator for the city's consent decree with the Department of Justice. Jackson also enjoys semi-frequent get-togethers with the moneyed, corporate consiglieres representing the backbone of his support in the business community — Beth Mooney, Albert Ratner, Joe Roman, David Larue, Sam Miller, etc.

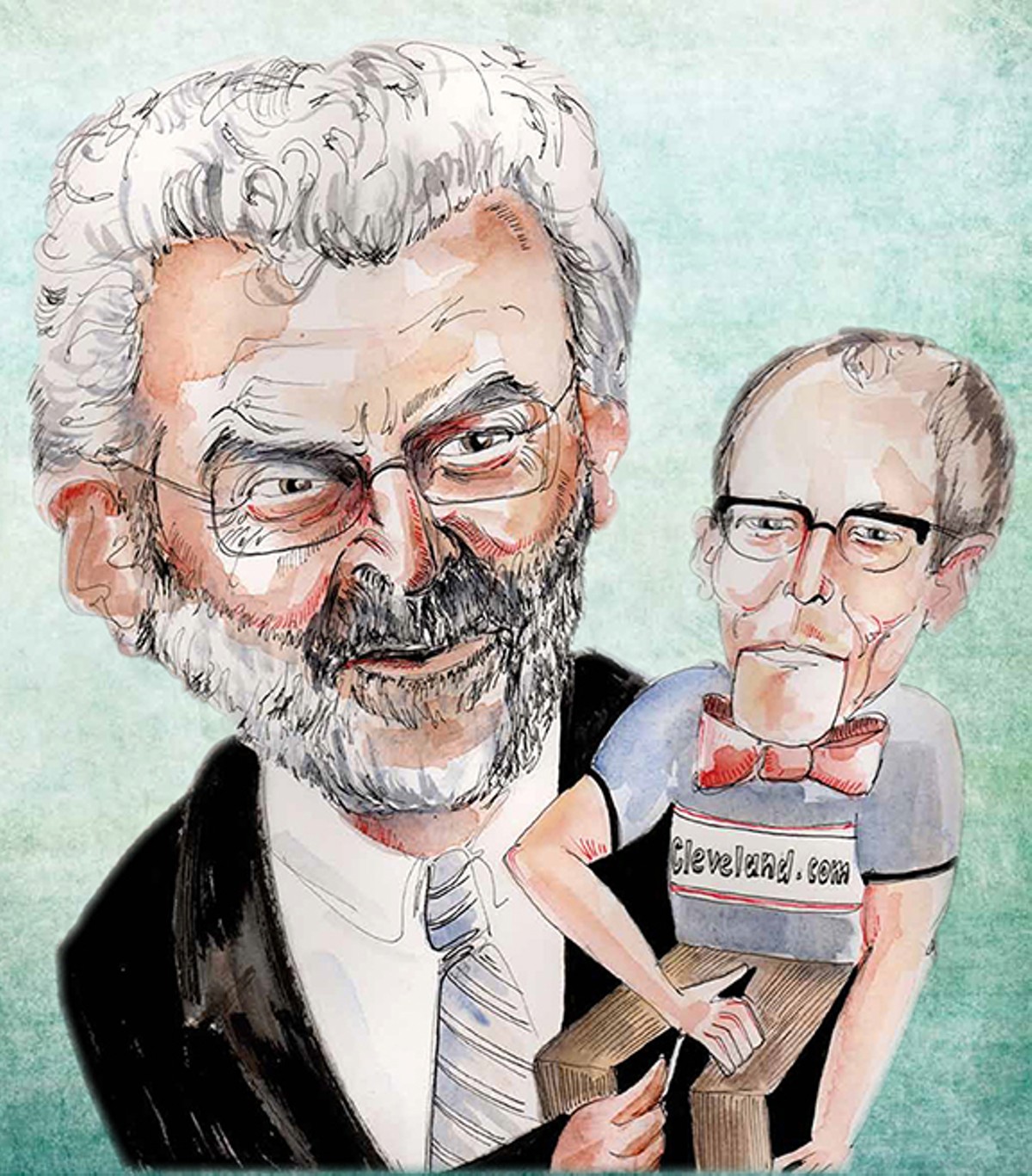

But one name stands out in a review of a full year of the mayor's calendar, November 2015 to November 2016: Chris Quinn, the editor of Advance Ohio, better known as Cleveland.com. Outside of government officials, Quinn got more face time with Frank Jackson than anyone: 11 individual one-on-one meetings in addition to at least six trips by the mayor to 1801 Superior Ave. to visit the Cleveland.com/Plain Dealer editorial board.

This professional bromance hasn't gone unnoticed inside or outside of City Hall. Sources within the city's journalism and political communities feel, and worry, that the frequency of the get-togethers, and Cleveland.com's coverage of Jackson, show that Jackson is the partner more firmly in control.

"They definitely have a close relationship," a City Hall source who requested anonymity as to speak freely told Scene. "It seems as if there is ever an issue specifically involving the mayor, he calls Chris and things are fixed. I don't know if it is just out of respect for each other but it happens frequently — if he's misquoted or his position isn't firmly stated or he just feels a piece is lacking something in general. He also pitches Chris on a lot of stories."

"Reading Cleveland.com you get a really good sense of what the mayor's thinking," says one local newsroom leader, "but not much else."

Chris Quinn has been with the PD for more than 17 years now. Back at the beginning of his Northeast Ohio tenure, when he arrived from the Orlando Sentinel, he covered City Hall. And by all accounts he was a sharp and tenacious reporter.

This was the Mike White era, when Jackson was a councilman, and the mayor-cum-alpaca farmer actively shitlisted the Plain Dealer for what he felt was unfair coverage. White's petty, vindictive crusade included releasing public records requested by the paper directly to competitors and tossing a PD reporter from a bombshell announcement, at a public elementary school, that he wouldn't be seeking a fourth term.

Quinn, for his part, once sent a letter requesting an interview with White after the mayor had surgery for hammertoe and scribbled, "a common cause of it is the wearing of high heels ... . Is it possible he used lifts under his heels?" White released the letter publicly.

The evolution from a no-nonsense reporter who fearlessly and nastily (and maybe regrettably) asked about the mayor wearing high heels to an editor who seems to have rather relished his ascension into Cleveland's comfy and comingling elite is strange, especially given his resume.

The Plain Dealer itself, of course, has mellowed and shrunk — through attrition, through advertising declines, and through its owner's unique brand of ineptitude. In 2013, Advance Publications, in a transparent union-busting schism scheme, stunned employees by unveiling a "digital-first" company called Northeast Ohio Media Group (non-union) from the Plain Dealer proper (union) and pared home-delivery of the paper back to three days a week. The clunky Northeast Ohio Media Group moniker was eventually dropped in favor of Cleveland.com. Further, the parent "digital marketing and advertising company" formerly known as NEOMG was renamed Advance Ohio in mid-2016.

If you're an outsider unfamiliar with Cleveland's media past and are a little confused at what it means, know that you're not alone. The mad-libs rebranding was not only hard to follow but also did exactly zero in service of the readers who saw, and see, Cleveland.com reporting in the print version of the Plain Dealer and Plain Dealer reporting on Cleveland.com.

It was Chris Quinn who Advance Publications tapped to lead the newsroom of whatever it is you want to call Cleveland.com after the split. It was a sensible choice: After covering City Hall for the PD, Quinn had risen in the ranks to deputy metro editor and then metro editor. In both cases, those familiar with his direction say, Quinn maintained a healthy but energetic adversarial bent on City Hall.

He seemed to carry that over after his promotion too, despite the internal organizational upheaval. Cleveland.com went aggressively after Jackson on patronage hires, unfulfilled campaign promises, and his relationship with city council.

The man who led that charge is unrecognizable to those who know him and who have followed the PD and Cleveland.com's once robust City Hall beat and the desiccated husk it has become. Multiple people have described a burgeoning ego that's ridden shotgun with his rise in rank (Quinn was recently again promoted, to editor and president of Advance Ohio). The reporter slinging rocks at the powered elite has now become one of them, and a stubborn one at that.

Roldo Bartimole is the closest thing Cleveland has to a media watchdog. He has persistently and passionately kept tabs on the PD/Cleveland.com for decades. And while almost everyone interviewed for this story asked to remain anonymous — they were talking about two of the most powerful men in Cleveland, after all — Bartimole has no such qualms.

"The coverage of the mayor himself has been soft. There's plenty on the record going back years to be critical about. It doesn't seem to be of interest at the PD," says Bartimole. "Quinn was a dogged reporter during Mayor Michael White's final years. His animosity toward White is a complete contrast with his attitude toward Jackson. He has totally failed to have his staff meet that standard in coverage of Jackson. There just have been too many missed opportunities to point out Jackson's faults."

Jackson's faults are indeed fertile and necessary ground. But while Cleveland.com has delved into some of his missteps — the city's inept maintenance and deployment of snow plows, the perpetual mess at Hopkins, Cleveland Public Power levying hidden fees upon customers, Cleveland's expensive and yet futile efforts at road repair — it devotes far more effort and space to his defense than to his prosecution. That's especially true of the editorial board, of which Quinn is a member and influential force, and for Quinn's appearances on WCPN's reporter's roundtable, where he can regularly be heard carrying Jackson's water on issues from Public Square to the consent decree.

The result? A feeling in City Hall that Quinn is receptive to pushback when it comes to coverage the mayor finds negative. (Since the mayor is filo-dough thin-skinned, it happens often.) And there's newsroom concern that pieces poised to land square punches on Jackson are pulled short, that leashes are kept on, that criticism is neutered.

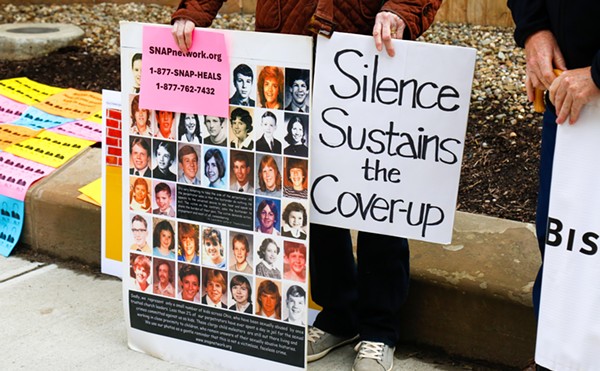

The problems, some sources say, began in January 2015. Cleveland.com had just launched a series called "Forcing Change," written by Cleveland.com's Leila Atassi (then the City Hall beat reporter) and Plain Dealer reporter Rachel Dissell in a rare example of reporters from the two organizations being allowed to work together. The multi-part series unfurled over two weeks, examining 60 lawsuits against the city of Cleveland and the police department over the previous decade alleging violent force. In all, the city dished out some $8 million in settlements or judgments in the cases.

Jackson wasn't pleased with the series. He, chief of staff Ken Silliman and others were incensed. They felt City Hall's side of the story hadn't been adequately represented. Someone in the mayor's circle suggested opening a line of communication with Cleveland.com, one that hadn't really existed then, at least not to that degree. "They just keep beating you up," one person told the mayor.

Meetings were arranged. By the end, according to a source familiar with the conversation, Quinn had "apologized to Frank for the tenor of the story."

You'd forgive any growing unease among reporters after that, especially when those meetings began to happen on a monthly basis.

Quinn, for his part, had no interest in speaking to Scene for this story. "Given your publication's penchant for publishing fiction about cleveland.com and its staff in your lowbrow quest to harm our reputation, I don't consider yours to be a responsible news organization. As such, I decline to speak with you."

***

It is natural, and in fact necessary, for the mayor to have a working relationship with the leader of the largest media outlet in town. Cleveland.com and the Plain Dealer are the largest conduit to the public's general understanding of the city and its issues. They set the tone and largely decide what is and what isn't news. Various outlets, including the TV stations, follow in their wake. It makes sense for Jackson and his staff to want to talk to the biggest megaphone around. As one City Hall staffer noted, "I think everyone feels that it's important for the city's message that the Plain Dealer get things right, so they take more time with them."

But while City Hall has good reason to schmooze the daily, the paper has squandered its access on rah-rah cheerleading that fails to raise the big questions, much less answer them.

The coverage of the Q Transformation deal is a good example.

We've known for two years now that the Cavs approached Cuyahoga County with a plan for a $140 million makeover and upgrade on Quicken Loans arena, splitting the cost with public and private money.

On the morning of Dec. 13, 2016, announcements went out that all the major players would be holding a press conference at 2 p.m. to announce the deal. Just as Len Komoroski, Armond Budish and Frank Jackson publicly unveiled the plan, Cleveland.com published an entire special package on the deal. To the minute, actually, which made sentences like this, "The plan to fund a $140-million renovation of Quicken Loans Arena was announced Tuesday to much fanfare and celebration," published as the announcement was being made, sound very weird. Who was celebrating? Where was the fanfare?

Budish and the Cavs, at the coordination of Eliza Wing, the county's chief communications officer, had earlier visited Cleveland.com and walked through the details. In an internal email that morning, Quinn boasted to staff, "We've spent weeks arranging for exclusive early access to everything involved in this story. We have it covered."

Which makes the resulting product even more disappointing. Then and now Cleveland.com's coverage remains so buoyantly boostertastic as to resemble an armada of pom-poms floating down the Cuyahoga River, right past where Dan Gilbert has long promised and failed to build phase two of the casino.

The original series aimed to be both digestible in format (lists, naturally) and language. "We love our sports teams — but man, do we hate the notion of using taxpayer dollars to pay for arenas and stadiums to further enrich players and team owners," went one folksy riff.

Yet despite that, and despite the fact that the project had been, by their own account, under scrutiny for the better part of a year, the paper parroted the talking points of Budish and the Cavs, many of which have since been proven untrue.

For example, the paper initially trumpeted that funding would be a 50-50 split. It's not; with interest on the bonds, the price tag comes to some $282 million. The public's portion of that bill: $160 million. They also regurgitated data from a report commissioned by the Cavs by Conventions, Sports & Leisure International in Texas, a company whose whole business depends on justifying stadiums and convention centers, which is reason enough to be skeptical of the data.

Worse still, headlines covering the report, including "The Q averages 2 million guests, $245 million in direct spending a year," are simply false. The report is very clear that the $245 million figure is for 2016 and includes $45 million directly connected to the RNC. Twenty-five percent of that total figure is substitute spending — money people would spend somewhere else locally, if not for the Gateway district.

The content itself is no better, littered with tidbits that sound directly like Quicken Loans talking points left unchecked. For instance: "Less than 25 percent of the events at the Q are related to the Cavs. Yet, the Cavs point out, Gilbert is willing to invest millions of his own money in a facility that he not only doesn't own, but that would become a public liability if his team were to leave."

Yes, Cleveland.com was on the bleeding edge of stoking the (unfounded and unchallenged) fear that the Cavs would leave town without a deal. The piece also never explains that not only does Gilbert own the Monsters and Gladiators, which play at the arena, but that Quicken Loans runs and profits from every other private event at the arena. The Cavs were taken at their word, no questions asked.

In short, Cleveland.com published at least nine stories out of the gate before the press conference was even over, all culled from access to the likes of Budish and Cavs' executives, filled with little but rubber-stamp admiration. It didn't feel so much that the site scored a scoop but rather that they were partners in the roll out.

That support hasn't waned. The editorial board has since twice opined, breathlessly, of the glorious plan, calling it a "sharply crafted deal" before county council could even finish public comment and deliberations on the topic. And, after opposition arose, they chimed in again. "Despite attempts at revisionist history" the public should "leave aside the small-minded grousing," never mind the "second-guessing intended to distract attention from the plain and obvious benefits" and remember that "none of the 11th-hour finger-pointing can devalue the facts."

The condescending tone was bad enough. Worse yet was how the board threw their own colleague under the bus.

In March of this year, reporter Karen Farkas had written a story after talking to former county exec Ed FitzGerald. He'd been approached by the Cavs with the same offer while in office and turned it down. He reiterated why he'd been against the deal, which was interesting because by most accounts it was the same deal on the table now, a $140 million renovation split "50-50."

Budish, while stoking fears that Dan Gilbert would tear away the Cavs from LeBron's backyard, had insisted that he'd negotiated the most important part of the deal, by his estimation: a lease extension by the Cavs. Farkas' reporting showed otherwise. The Cavs had brought a lease extension to the table as part of the original deal, FitzGerald said.

It was no small tidbit. As the county and the city prepare to hand over hundreds of millions of dollars to a billionaire, it's only right that citizens ask what exactly has been negotiated on their behalf.

The editorial board was having none of it and could barely hide their contempt. Instead of recognizing or even mentioning that, by their own coverage's account, Budish had lied to their reporter and the taxpayers, they took a potshot at Ed FitzGerald's personal life and failed gubernatorial campaign.

Lowbrow efforts to damage reputations, indeed.

The deal did and does beg for scrutiny, and Cleveland.com seems either uninterested in or incapable of providing it for their readers.

***

Last year, Mayor Jackson began earnestly working on a project that would spend $2.3 million to build an eastside, inner-city dirt bike track and park. There's a fascinating and headline-grabbing subculture of mostly black, mostly urban men who ride dirt bikes on city streets. (Scene, in fact, covered them in a May 2015 cover story.) They pop wheelies and course through the streets breaking a small litany of laws — bikes are largely not registered, and they blow through stoplights and disobey other traffic codes. There have been accidents, some gravely serious.

Jackson's idea was to build a park for the riders — to help get them off city streets, to show the city is listening to their needs. The plan would eventually, and contentiously, be approved by a divided city council in January of this year.

In October, months prior to the vote, Cleveland.com launched a special series, including five stories and video accompaniments called "Bike Life," that heartily endorsed the idea. It was largely bereft of any criticism — of spending $2.3 million when the city had other needs, of spending the money on a dirt bike track when the city's recreation centers are badly in need of repairs. It asked that readers ignore the mayor's personal connection — his grandson is part of the group, and has been arrested twice for riding illegally — and brush aside the other concerns.

In a vacuum, the series wouldn't be troublesome. But enterprising takeouts with that amount of resources are something that Cleveland.com rarely does. And it had Quinn's fingerprints all over it.

One writer defends the idea, arguing that the motorbike culture and park produced intersections with crime and violence and neighborhoods that were worth exploring. But, with its quivering support and probable City Hall origins, the lack of any substantive voice opposing the idea (and there was no shortage of those voices) seemed odd. "I wonder if it was verboten," notes one writer on the lack of critical questions in the package.

As one person familiar with Quinn's management style points out, "He doesn't just assign stories; he assigns angles. You know what you're supposed to get when you walk out the door."

Perspective like that might make a reader think differently of, or at least be more skeptical about, some of the paper's coverage, including a recent look at Jackson's "comprehensive plan" for youth violence.

A recent look at Jackson's three terms, published on Jan. 31, gave equal weight to criticism of the mayor and his side of the story. The downsides, soft-pedaled as they were, nevertheless drew the ire of Jackson. And he let Cleveland.com know it the next day when he visited the editorial board to, as is his tradition, unveil the proposed city budget.

The resulting article was titled "Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson's 2017 budget improves city services with new income tax." Not "spends more money on city services," or, "hopes to improve city services," because never before has Cleveland dumped millions of dollars into something only to screw it up.

Two weeks later, they followed it with a fawning, long feature, "Here's how mayor Frank Jackson plans to quell violence, improve lives of inner-city youth."

"This year, Jackson has launched a comprehensive plan to address the youth violence epidemic facing the city. It draws together violence intervention, street outreach, social programming, workforce development and community policing, under the coordination of Duane Deskins, the city's new chief of Prevention, Intervention and Opportunity for Youth," the article began — and continued in that vein for 1,400 words.

But for all its length, there was little examination of Jackson's failed efforts in the past, nor dissenting views.

Nor did it mention that Jackson's appointee, Deskins, was recently in headlines for performance at his previous job at the prosecutor's office: There, the Juvenile Division, under his leadership, failed to follow up on dozens of sexual assault cases that sat dormant for years, according to newly elected county prosecutor Mike O'Malley.

***

Mayor Jackson is a reluctant politician who eschews publicity and remains privately guarded, if not outwardly unenthusiastic. He's a 180-degree turn from politicians like Jeff Johnson and Zack Reed, who seem most comfortable when a mic or TV camera is in front of them. A recent press day where he sat down with WCPN's Rick Jackson and WKYC for extended interviews are anomalies: It's campaign season and even a relative media hermit like Frank knows he needs some play on the local airwaves.

Outside of re-election efforts, though, everyone but Cleveland.com is left to chase the story and pick up on Jackson's message through them.

In keeping, repeated requests to interview the mayor on this and other topics were declined through a city spokesperson. Specific questions regarding the mayor's general views of his relationship with the media and how his administration has been covered went unanswered. A spokesperson did at one point in January call to offer an off-the-record meeting with Jackson, only to call back 10 minutes later with the message, "The mayor says thanks but no thanks." (The same spokesperson attempted to defend the allocation of the mayor's time with media by saying Jackson spoke to plenty of local reporters in the leadup to the RNC last summer.)

It's not just Scene getting cut out. TV stations are fuming.

The Public Square/RTA battle is a good example. Jackson, as Clevelanders well know, closed the square to public transit and petulantly stood firm and defended his reasoning (safety concerns, naturally) for weeks and months in the face of a $12 million penalty by the Federal Transit Administration. On Feb. 7, the RTA released the results of a traffic study that said the square should be reopened to buses.

Later that day, as it became clear this ran contrary to the mayor's opinion, a press conference was organized. Reporters at City Hall were welcomed by the city's chief operating officer Darnell Brown and police chief Calvin Williams.

The mayor was nowhere to be found. But as it turned out, Jackson had already had his say on the matter.

Earlier that day, the mayor talked to Quinn, who along with the editorial board had defended Jackson on the topic through the duration of the spectacle, and some reporters, including the Plain Dealer's transportation writer. The resulting PD article was tough on Jackson. But that didn't assuage the feelings of reporters at every other outlet in town who expected the chance to ask Jackson questions directly.

Andrew Horansky of WKYC tweeted, "Mayor Jackson not present at this news conference. His Chief of Operations, asked twice, hasn't explained where he is."

It was more than one-time sour grapes. Jackson's sheltered personality and Quinn's unique access have become a source of frustration for reporters who feel that Quinn's not doing his job and Jackson is preventing them from doing theirs.

"If he wins a fourth term," said one competing reporter, "he simply can't keep operating this way."

***

There is sympathy to be had for Chris Quinn. Like others in his position around the country, he's leading a newsroom that looks much different than the one he cut his teeth in. In addition to City Hall and cops and courts and politics and sports, he's now in charge of an operation that also pumps out 12-part slideshows on the cutest cats of Cleveland, articles on "5 sexy outfits for Valentine's Day," and a near-endless feed of headlines like "50 movie comedies that made Millennials LOL" and "Brief history of Nicki Minaj's obsession with LeBron James." He's navigating that landscape with a bastion of young reporters in a "digital-first" operation that somehow still feels like it's always playing digital catch-up.

He's also navigating what is still a strange and bitter split between Cleveland.com and the Plain Dealer, each with their own fiefdoms and beats, and little cooperation between the two. At one point last year, for example, Cleveland.com and the PD both sent a reporter to a conference in Baltimore without knowing the other had planned on sending a writer there.

Still, it's distressing to watch the crumbling of a once-great journalistic institution. It's been eons since the publication has been a finalist for, let alone won, a major award. And staffing decisions continue to show wanton disregard for reporting the people's business. Atassi, for instance — whose sourcing and in-depth knowledge of City Hall Quinn championed in an editorial last year, noting, "Without analysis, perspective and context, what we do is just stenography" —recently departed from the City Hall beat. Surely Bob Higgs, who took over the gig, will do a fine job. But with the mayoral election this fall, it's an odd decision that sacrifices serious institutional knowledge. (Atassi, who declined to comment for this story, says that she's working on a longterm project for the foreseeable future.)

The "stenography" gloat is even emptier when you talk about the county. Cleveland.com has assigned Karen Farkas to cover not just Cuyahoga County, but also higher education and gambling. In the land of Dimora, the county beat is now considered one-third of a job.

If you'll forgive the staffing exegesis, there is a point: Maybe, in the face of dwindling resources and a reshaped editorial newsroom and focus, Quinn sees access to Jackson as something worth nurturing and holding onto. Maybe the battle scars of the Plain Dealer vs. Mike White era have informed his view of the subject/editor relationship.

"Why would I talk to a media outlet that purposefully distorts the truth?" White told the paper back in the day. "The decision to phase out the Plain Dealer was made after years of attempting to obtain fairness and balance in its coverage of my administration. Clearly, we were unsuccessful."

At the time, the PD's editor in chief Doug Clifton — Quinn's boss — bristled. "Every politician would like to be able to write the stories about his or her administration and have them be filled with admiration."

That's not what's happening now, to be clear. But some fifteen years later, Cleveland's biggest media outlet showers mostly admiration on Jackson's administration. The chilly détente between City Hall and 1801 Superior has thawed to a warm, rolling river with Jackson and Quinn in a canoe enjoying the scenery. Who's got the oars?

The question's importance is summed up no better than by Quinn himself. "Without analysis, perspective and context, what we do is just stenography."