These paintings of ancient Greek vases and the magically endowed miniature people who populate them are part of In The Details, a show now on display at the Cleveland Play House Gallery that includes work by two other local artists. Ken Coon searches Cleveland, with intermittent success, not for maidens, but for eerie nooks and crannies that lend a film-noirish edge to the commonplace. Kathy Crowther's nature watercolors serve as a foil for Boyle's sophistication and Coon's mystifications. Unfortunately, her work is hobbled by an impersonal precision that speaks volumes about commitment to craft, but lacks an expressive goal, which would make all that craftsmanship worthwhile.

Coon, a Perry, Ohio, artist, is fascinated with the poetic qualities of ordinary objects. Gas stations, delicatessen storefronts bearing Coca-Cola ads and methodical announcements about every scrap of food available within--these are his raw materials, just as they were Edward Hopper's. Throughout the '30s and '40s, Hopper painted lonely usherettes and rural gas stations at dusk. In a 1940 oil called simply "Gas," Hopper contrasted a series of orange gas pumps with a road lined by an expanse of dark trees, the gas station suggesting an island of certainty where people could refuel and hinting at the dark undercurrent running through Mayberry.

Hopper was like a chemist, knowing exactly what to include in his paintings and in what quantities. Coon, by contrast, grounds his images in a multitude of random specifics. For example, the older artist rarely called attention to the specifics in storefront ads. But for Coon, this seems to be essential. Nevertheless, either by serendipity or a flash of insight, he sometimes hits the mark.

Because there are only about a dozen of Coon's works here, it's hard to tell how representative the fine acrylic called "Dairy Dock" is. But by any measure, it's his most striking work among those shown and the most interesting piece in the entire Play House exhibit. The real-life Dairy Dock seems to be a Cleveland Mom and Pop version of Dairy Queen that specializes in soft-serve treats. But Coon, by distilling atmo-sphere with a sure touch, suggests the melancholy of a summer evening during which nothing seems to happen, but is nevertheless teeming with disturbing little details that seem not to make sense.

Coon achieves this sense of mystery and foreboding through an inventive use of both color and design. The composition is arranged geometrically. The diagonals of the garish dairy cone that forms part of the store's logo, the American flag that juts from the concession stand roof, and the trees across the street are intersected by a series of verticals--a massive post which supports the roof, the figure of a girl who stands at the counter, the windows of the stand. Furthermore, the golden color of the sandwich menu board is echoed in the color of the post as well as in the various bags of snack items that hang in the window. By methodically leading the viewer's eye around the canvas, Coon calls attention to the too-blue sky, the lone car on the road, and the forest across the street--the darkest portion of which coincides with the American flag. Something isn't right in Cleveland, but Coon isn't saying exactly what. This is a fine example of effective poetic suggestion and, though Hopper is an obvious model, Coon builds his own momentum in this work.

Other works by Coon are not nearly as effective. Images of used-car dealerships and delicatessen storefronts seem more about documenting specific spots in Cleveland, with little of the Dairy Dock poetic undertow. Details pile up, but in the absence of a larger vision to support, they merely fill up space. An example of this problem is Coon's "At Sharies," in which a Hopperesque debutante in jeans sits on the front steps of a deli restaurant. A series of ads blares out the availability of Coke, Pepsi, and pizza. These are contrasted with a "Sorry, We're Closed" sign and announcements about new hours.

The point, modest to the point of banality, seems to be that the lone human figure is dwarfed by all these ads. If, on the other hand, Coon is encouraging the viewer to make a connection between the woman's psychological state and the elliptical phrases in the ads, he is doing it without subtlety. Such a crude symbolic modus operandi can work when an artist wants to paint in broad satirical strokes (as in Stanley Kubrick's film Dr. Strangelove, where a battle on an Air Force base between people on the same side takes place, incongruously, in front of a huge "Peace Is Our Profession" sign). But it's not good for communicating small psychological insights. Coon needs to hint more then he proclaims.

Kathy Crowther's watercolors are of birds at rest. The Chagrin Falls resident encloses the birds in ornamental designs that reflect her interest in rug borders. By employing a dry paper technique that allows her to control the thickness of each stroke, Crowther eschews the large washes often associated with the watercolor medium. Instead, the interplay in many of these works between large simple forms and minute swirling design elements strongly suggests textile art.

In addition to the birds, which are the dramatis personae in these seven works, Crowther employs a series of decorative motifs that include flowers, berries, and checkered design elements. Although the birds are carefully rendered--Crowther differentiates their shapes and their colors--they seem less a part of nature than an accompaniment to her complex borders. The problem, in short, is that Crowther recognizes no distinction between expressive main material and decorative accompaniment. The birds become servants of all the filigree. Consequently, the result is less an homage to the wonderful varieties in nature than an evocation of the decorative strategies found on Christmas wrapping paper or on the cover of Hallmark Christmas cards.

Martin Boyle's postmodern take on ancient Greece reminds one of Keats by way of the Twilight Zone episode about the department store mannequins who, each weekend, took turns circulating among the real people. Keats and Serling, unfortunately, go together about as well as asparagus and caramel sauce. Boyle's work in this vein is faintly amusing, but it would be a mistake to demand of it anything more than a couple of chuckles. For example, in "Put the Cork in the Bottle," an oil on linen, the little black figures jump free from their vase and celebrate. One guy dances on a wine bottle, while nearby, an archaic couple flirt.

Boyle, who hails from Kent, is the illusionist who makes it happen by placing these shenanigans in canvases that fool the eye. Their encapsulated world simulates those half-moon-shaped concrete niches carved into the walls of Mediterranean restaurants that typically do double duty as ethnic figurine stands and display pedestals for the house wine. Perhaps that's the point. Greek pottery from the fourth century B.C. dispensed wine to tipsy celebrants in religious rituals. Newly liberated and dunked into the twentieth century, all these archaic people can hope for is a dance on an empty wine bottle from a Mediterranean restaurant that reeks of oil and garlic. Submitted for your approval: the decline of Western Civilization a la Boyle.

Moving into headier territory is Boyle's "I Can't Tell a Lie," which seems to be about the artistic process. The notion that artists are in the business of lying is hardly new. Picasso once suggested as much when he said that "all art is a lie, but we believe it by the might of its right." Boyle's variation on this theme has little might, but does provide some food for thought.

For one thing, the work is linen on wood--but the artist has painted the outer borders of the linen so that they resemble a veined piece of wood. Next, Boyle set up a still life that consists of three cherries, a pitcher filled with flowers, a George Washington penny bank, and a jar that contains cherries submerged in a clear liquid. The cherries undergo a curious transformation if the image is read from left to right. At first they are bare, the way they appear when freshly picked from a tree. They end up in a closed container submerged in what could be sugar syrup, water, or, more ominously, formaldehyde.

Although the precise meaning of these steps is up for grabs, the main point in all this is clear: Artists take what is found in nature and subject it to all kinds of changes. The impulse in art is always to transform, just as a lie transforms the truth.

Keats's urn dwellers were ardent and avidly pursued an ideal. Boyle's are, by contrast, satiated and don't have a clue about how to spend their time now that they are free from their confining ceramic existence. Hopper was poetic and left out as much as he put in. Coon, with the exception of the fine Dairy Dock, puts in so much that fact-stacking verisimilitude cancels out any fleeting chance for poetry. Much of the work in this exhibit runs in this vein: precise in a negative way. Attention to detail, when such detail doesn't support a broader conception, is the enemy of poetry. And when, as in most of this exhibit, detail is not accompanied by discrimination, craft becomes king and artistry gets short shrift.

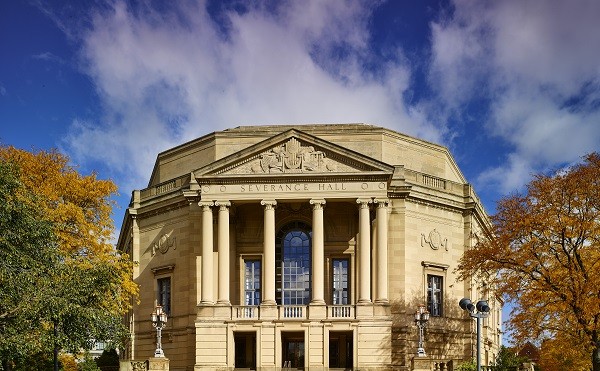

In The Details, through June 6 at the Cleveland Play House Art Gallery, Bolton Theater Lobby, 8500 Euclid Avenue, 216-795-7000.