To describe what he does for a living would be akin to listing a dozen other people's r*sum*s. He is curator and detective, scholar and archivist, teacher and cheerleader, salesman and bodyguard. For nearly 20 years, he has gone in movie studios' vaults and dug up cinema's detritus, polishing off the dust until discarded junk becomes priceless artifact. Becker rescues movies for a living -- from the studios' graveyards and, on occasion, from the filmmakers themselves. Without him, our knowledge and understanding of classic and contemporary cinema would be deficient, if not nonexistent.

There are no major awards for the kind of work Peter Becker and his partner Jonathan Turrell engage in, so the two will likely remain in the dark, where all good movie fans are at their most happy anyway. But without them, it's very possible Jean Renoir's Grand Illusion might have been lost to the ruin of old age. Without them, we might have had no idea that hours upon hours of footage were left out of Rob Reiner's This is Spinal Tap. Without them, we might have missed out on the pleasures of painter-turned-director Seijun Suzuki, whose 1966 pop-noir crime story Tokyo Drifter is less a movie than a cartoon-as-dream. And without them, we might have been spared the expansive director's cut of Armageddon, which is still awful no matter how pretty you dress it up.

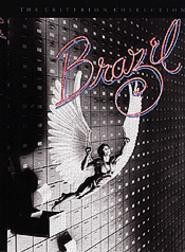

Becker and Turrell deserve so much credit for changing the way we watch movies...OK, and a little bit of the blame. The two are partners in the Criterion Collection: Becker is the company's director; Turrell, its CEO. In the early 1980s, both men carried on the work begun by their fathers, who founded the legendary Janus Films in the 1950s as a way to bring the best overseas filmmakers -- among them, Akira Kurosawa, Federico Fellini, Francois Truffaut, and Renoir -- into American theaters. The only difference is, Peter Becker and Jonathan Turrell bring the best of cinema into American homes, and allow anyone with access to a DVD player the opportunity to turn their living rooms into the world's greatest art-house theaters. Showing tonight and every night: Grand Illusion, The 400 Blows, The Third Man, M, and Rushmore, all presented in prints so immaculate they radiate off the television screen like three-dimensional holograms.

And you will have company beside you on the couch as you watch these movies. Writer-director Wes Anderson and his writing partner Owen Wilson will join you and explain every scene and storyboard for Rushmore. Martin Scorsese and Willem Dafoe will guide you through The Last Temptation of Christ. The Monty Python troupe, including John Cleese and Michael Palin, will dissect every laugh in Life of Brian. Then, they'll break out the coming-attraction trailers and shooting screenplays, after which they will load up the documentaries and screen tests. They will elucidate and energize their films in such a way you will feel as though you could go out tomorrow and make your own film.

"Criterion has made it possible to go to film school," says Owen Wilson. "Without the tuition."

Peter Becker has changed the way we watch movies, because his company has changed the way in which they are presented to the home audience, a far larger crowd than the theatrical one. He has wrung the mystery out of moviemaking; he has pulled back the curtain to reveal a dozen wizards holding cameras and boom mikes and screenplays. He has unearthed a good chunk of filmdom's history and given it to us for less than 30 bucks a disc. He has turned our home shelves into archives, our television sets into time capsules.

"We just try to leave movies better than we found them," says Becker, who co-founded Criterion just as the laserdisc format was appearing in the early 1980s.

Originally, the company existed only to preserve films as they slowly deteriorated. At the very most, the company -- which essentially leases films from studios -- existed as a sort of scholarly clearing house where critics would come and talk about movies they loved and explain to the viewer (ostensibly a fetishist or a fanatic) why the glowing images on their television screens remained important. But by the mid-'80s, directors such as Martin Scorsese and Michael Powell began laying down commentary tracks about their own films. It began a small, quiet revolution whose effects are only now being felt as movie studios scramble to release cleaned-up, dolled-up versions of their movies as special-edition DVDs loaded down with trailers, making-of documentaries, and director's commentaries.

"Criterion set out in the beginning to do something that no one else was doing at the time, which was employing the laserdisc medium in an innovative way, trying to make use of all the capacities of that media," Becker says. "I think fairly quickly our mission evolved from just making films available to trying to create a film archive, a film school for the home viewer. The theatrical experience is about total absorption: Either you give over to the magic of the film, or you don't, and afterward, you walk out and talk about it with your friends. When you have a film on your shelf at home, the idea was to start out with movies that would stand up to repeated viewing, that would stand up to more intensive discussion than the kind of discussion you have over a bite of dinner after the movie."

Criterion has made us smarter filmgoers and created better filmmakers: Kevin Smith (Chasing Amy, Clerks), Wes Anderson, and the Hughes brothers (Menace II Society) insist that a great deal of their film-school education came from repeated viewings of Criterion's treasure-chest laserdiscs. Now, we almost take for granted such "added value" bonuses; we expect them on our DVDs and are disappointed when a studio cheaps out and fails to include a director's commentary or deleted scenes. Criterion has not only reinvented the home-video industry; it has also spoiled us. Now, studios scramble to play catch-up, replacing their shoddy product with fancy extras. On May 16, Fox will release a special-edition Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, complete with documentary and interviews and commentary tracks, that renders the earlier, cheaper version a moot point.

The cutting-room floor is a thing of the past; it now serves as a repository. Steven Spielberg, who has so far been reluctant to release his best films on DVD, announced last week that Jaws will surface July 11 with myriad deleted scenes. Ridley Scott's two-and-a-half-hour bloody, beautiful spectacle Gladiator opens this week, and already Scott has sent notice that the DVD version will contain at least an hour's worth of deleted footage. And during an interview last September, Three Kings director David O. Russell explained that trimming his "favorite scenes" from his film wasn't quite so painful, since he knew he could include them on the DVD.

But if those lost scenes had been included in the theatrical Three Kings, it would have been an inferior film. They slow the action, explain too much, and leave little to the imagination. Such is the case with so many deleted scenes: They were cut for a reason, and more often than not, audiences wince when they show up on DVD. For every The Sixth Sense, whose deleted scenes explain previously unanswered questions, there's something like Ghostbusters, which contains a dozen humorless outtakes that appear to have been lifted from a Bergman film.

DVDs have become their own kind of art form -- a "meta art form," to use Becker's phrase. The industry also has created immediate revisionist history: Films that open today will look completely different when they arrive in stores tomorrow. DVDs offer not only "master-quality" versions of films (thus rendering the videotape as necessary and reliable as the eight-track tape), but they also allow filmmakers the opportunity to reshape a film for home release. They're no longer bound to the versions studios and test audiences "approved." Directors may not have free rein in the theater, but they can wreak havoc once allowed in our homes.

Only last week, Richard Donner announced he was finally releasing Superman: The Movie on DVD with an additional 15 minutes of previously unseen footage woven into the film. Of course, that begs the question: Can a film ever be "finished" in the digital age? George Lucas not only went in and added computer-generated effects to the Star Wars trilogy; he also excised scenes of violence, gutting the first film of its initial resonance. Directors who are unhappy with the theatrical releases of their films can now go in and add all their gold and garbage. They can tinker ad infinitum. Last month, Fox Home Video released James Cameron's The Abyss with 28 minutes of footage that were deleted when the film tested poorly. The version of Cameron's Aliens available on DVD is 15 minutes longer than its theatrical release, meaning there are whole generations out there who think the film always contained the subplot about Ripley's daughter.

DVDs explain how a director cut a woman in half; they take the mystery out of the how-they-done-it. To that end, fully loaded special-edition discs could very well ruin our enjoyment of our favorite movies. They threaten to fill in too many blanks, shoving aside the audience in the filmmaker's rush to explain every scene and unveil every storyboard. Movies are about getting lost in the dark, and DVDs, with their documentaries and production stills and video tours of production sites, threaten to shine too much light on the subject. They can be like books about books; they can destroy the illusion, ruin the fun. At their best, the movies belong to the audience. Perhaps our ability to interpret them and enjoy them will be ruined with the filmmaker leaning over our shoulders, breathing in our ears. Some filmmakers, among them Brian De Palma and Peter Weir, know this, which is why they refuse to record commentaries for their DVDs.

"On the This is Spinal Tap DVD, Rob Reiner talks about why he declined to do A Few Good Men Criterion edition," says Becker. "He says he declined because filmmakers are like magicians, and it's their job to get out there and do the trick and wow the audience and leave them wondering how they do that. He said, "By coming out here and telling you how I do the trick, I am going to decrease your enjoyment of this film. I may increase your understanding, but I am going to decrease your enjoyment.' I think that's a very valid perspective, but that's what it is, that's what we do. We unravel the magic of the movies."