Art at the End of the Millennium: Contemporary Art From the Milwaukee Art Museum seems designed to encourage reflection on a question stated in an accompanying exhibit pamphlet: "Will art express doubt and cynicism in the 21st century, or will a new holistic, optimistic view emerge? Only time will tell." Fittingly, the inquiry is open-ended, but it also assumes that current art, en masse, is all about doubt and cynicism. Certainly, many of the works here are saturated with a sense of anxiety, and some even seem preoccupied with death. However, attempting to fit 29 stylistically heterogeneous works under a broad thematic umbrella is to risk the possibility of blunting the impact of individual pieces.

Although some of these artists hint that art might have therapeutic power, some believe that art is simply a part of the life process (Gerhard Richter's enormous psychedelic oil called "Breath" seems to celebrate the expressive potential of paint by lending quirky immediacy to torrents of thickly applied layers of borderless pink, orange, and blue forms that dissolve into one another and thereby blur any distinction between background and foreground). Some artists have a political agenda. Others deny art any social function and insist on its autonomy. In other words, this exhibit is really about spending time with individual creations which, with their single-minded intensity, seem to deny the existence of everything except the immediate work.

Anselm Kiefer's enormous canvas titled "Midgard" is one of the highlights of the exhibit. It has all the hallmarks of this famous German artist's style — aggressive handling of oil, emulsion, and acrylic, a doom-laden subject (here, the mythical serpent called Midgard which, in Norwegian legend, killed the god of thunder and precipitated the end of the world), and a disregard for the niceties of long-term preservation (it's quite a coup for the Akron Art Museum to have been given the privilege of displaying this fragile piece).

One sign of an artwork's power is the range of associations it calls forth. This work manages to simultaneously evoke the apocalyptic musical dramas of Richard Wagner, the chilling photographs of Hiroshima taken after it was bombed, and, finally, Berlin at the end of the war, when Albert Speer's massive neoclassical buildings were being reduced to rubble by Allied air attacks. Even the piece's passages of vigorous splotches of white and pointillistic daubs of gray offer no respite from the blackened landscape. This painting, aside from giving us a fair glimpse into the mind and working methods of a grimly determined artist, is a compelling example of a modern work which, in no-holds-barred fashion, seems convinced that the existence of the world is not a comfortable fact but a tenuous victory that is always under attack.

Philip Guston became famous in the early '50s as one of the second wave of New York abstract expressionists, but by the time he painted "Table Top" in 1979 he had switched to vaguely unsettling paintings of recognizable subject matter. The motifs in this work are familiar everyday objects — a salami sandwich, some cigarette butts, a pair of eyeglasses, a book, and some patterns that resemble the soles of shoes. Executed with thick brushstrokes and with a color scheme dominated by blood-reds, sludge-like browns, and sickly light purples, the effect is anything but familiar.

A work like this, unfortunately, seems more about the thickly brushed paint and grotesque color combinations than any desire to explore the implications of everyday objects. These objects may have had an ominous private significance for the artist, hence the bold and disturbing colors, but there is little going on compositionally that would lead the viewer to rethink the relationship between a salami sandwich and the sole of a shoe. (Although the speckled surface of the rye bread is echoed in the dotted shapes at the center, which resemble shoe soles, there seems to be no reason for this formal parallel.) This work is a riddle perhaps solvable only by Guston himself.

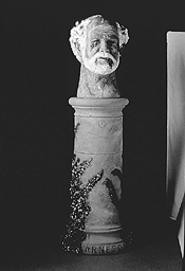

More successful at giving form to intensely private subject matter is Robert Arneson, whose ceramic self-portrait is as poignant as it is humorous. "Desolatus" is a funerary monument that the California sculptor created for himself. In it, the artist portrays himself as an ancient Greek or Roman philosopher who, unaccountably, has bits of green vine coming out of his mouth and nostrils. The vine, furthermore, is repeated at the base of the pedestal, which supports the massive head. The artist thus sees himself as an anachronism who will soon be pushing daisies and also as a distinguished member of his profession who is worthy of being remembered, as were ancient artists and thinkers in their own day. Arneson, who was influential in the development of ceramics as a major medium for sculpture, was not unjustified in thinking himself worthy of memorializing. "Desolatus" is autobiographical art that works: It's therapeutic on one level (Arneson executed it while recovering from a serious illness), and yet the subject matter — the reality of aging and the desire to be remembered — is universal.

Although conceptual artists like Jenny Holzer and Haim Steinbach create works that are as cool-blooded as those of neo-expressionists like Kiefer and Richter are hot-blooded, and though they are not crisply allusive in the manner of the Robert Arneson bust, they certainly do not lack ambition. Steinbach's specialty is taking trivial supermarket-style goods and carefully arranging them as in a shop window. The objects — anything from colored oil lava lamps (Austin Powers would approve) to chrome trash receptacles (the example in the Akron show) — are usually displayed on laminated wood shelves or stands veneered with chromium. The point is to elevate (literally as well as figuratively) everyday objects to the dignity of art. The polished chromium surfaces and the repeated patterns are not arresting in the art-gallery context, though. Presumably meant to simultaneously evoke a supermarket and a place of worship, Steinbach's installation never moves beyond its shiny chromium-plated surface appeal. Ravel in his Bolero created a monothematic masterpiece, but he didn't spend the rest of his career going down that road: Once was enough. Steinbach and others have mined this territory before, but they continue to hope that they can find significance in dross if only they package it correctly.

Jenny Holzer's work uses the structures of the mass media to sneak messages into the public arena. Her forte is in enlarging her one-liners and then placing them in spots where average viewers can see them and think about them. An example of her work: the huge electronic sign she set up in Times Square that boldly announced "Protect Me From What I Want." At Akron, Holzer is represented by a sign with yellow diodes that mimics the rapid-fire style of stock and bond reports at the Stock Exchange. Among the pearls of wisdom offered: "The Beginning of the War Will Be Secret" and "Outer Space Is Where You Discover Wonder."

Although Holzer attempts to courageously walk a tightrope between directness and superficiality, her experiments with in-your-face dramatics tend to fall on the side of superficiality. Her use of language is not special (short declarative sentences that are dry-eyed about the existence of pain in the world have been legion in French films since the beginning of the sound era), and the content recalls Saturday Night Live's "Deep Thoughts by Jack Handy."

Twentieth-century German artist and theorist Joseph Beuys had this to say of that gloomy Scandinavian Edvard Munch, whose downbeat oil painting "The Scream" has been admired for its throat-grabbing intensity ever since it was executed in 1893: "His symbols of dying can be understood as references to the end of an epoch and the beginning of a new one." Similarly, more than a hundred years later, the Akron Art Museum is attempting to define the contemporary world through these 29 works. The viewer, however, will best be served by appreciating the works on an individual basis.