"This is an old-time song by Hambone-Willy Johnson," Downchild says, in his English accent. He wishes he could play bars like this more often. It gives him the chance to rock out more than his usual coffeehouse gigs do. But Downchild is a traditional solo blues artist in a town where blues means blues-rock and traditional means dead-and-buried.

"It's the whole blues scene," he says a week later at Coventry's Caribou Coffee, as he sips on a hot chocolate. "And I think that's due to the style of music that's played today. I mean, if you listen to country, it's not real country; it's a bit like rock. If you listen to blues, it's almost the same. Basically, what you're talking about is McDonald's and Wendy's and Burger King music here. It's become generic. It all sounds goddamn the same."

All of which is a far cry from the music of his youth in England, where a generation starved for vitality and emotion ate up American blues.

"I got into the blues in the mid-'60s, when I saw Sonny Boy Williamson on the TV; that's when I really wanted to play the harmonica," Downchild says.

Taking his name from a Williamson tune, Downchild (a.k.a. Steve Brazier) formed his first band in '65, while still in school. The blues scene in England in the mid-'60s was vibrant, but hard to break into.

"The big record companies controlled most of it," Downchild says, a hint of bitterness in his voice. So, he spent the years playing in bars at night while working as a plasterer during the day. At the time, Downchild had some friends in England who were from Cleveland.

"They asked me to come and visit," Downchild says of his emigration to the U.S. in 1985. "So I came and visited. I met a lady. A year later, I got married."

In the States, Downchild fronted several now-defunct bands, singing and playing guitar and harmonica. And while the usual money and personality conflicts surely played a part in the eventual demise of these groups, Downchild's decision to forgo the band route in favor of a solo career was based on artistic choice.

"You're talking about music, and when the music ceases to sound to you like it should, or you feel the need for something else, you have to follow it," Downchild says. Otherwise, "you get a sense of shame and guilt that you're going out and playing these gigs, and you don't want to do it, but you need the money. That's a sad thing to do."

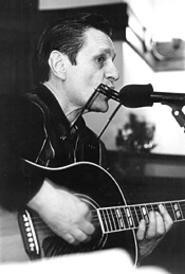

Playing solo best suits Downchild's earthy, distinctive style. While the tracks on his first album, They Call Me Mr. Downchild -- where he was backed by Robert Lockwood Jr., among others -- swung hard, the real gems were those that simply featured Downchild, a guitar, a harmonica, and a microphone. His second and most recent album, the far superior Behind the Sun, is devoted entirely to solo pieces: some acoustic, others electrified, but all originals.

And while Downchild's voice isn't the strongest, he makes up for it with his formidable harp playing and clear, almost delicate guitar work. On many songs, his guitar and harmonica lines practically sing to each other -- the call-and-response is so expressive, it's hard to believe that both sounds are coming from the same source.

But though going solo has been artistically gratifying for Downchild, it has left him with fewer opportunities to play out live.

"I don't fit in the blues clubs anymore, because I'm a solo act," he sighs. "They all want bands. I get people saying to me, 'Would you bring someone else with you?'"

So he plays the bookstores, the coffeehouses, the wine bars. And of course, there are limitations to what you can do while your audience eats scones and comes up with top-10 lists of poet suicides. Mainly, it's the electric side of Downchild's repertoire that suffers.

"I don't just play acoustic blues, so part of my act doesn't fit in the bookstores and coffeehouses, because I'm too loud," he explains. "I don't play my electric stuff very much, because I've got nowhere to do it."

These difficulties, however, haven't moved him to go down the more lucrative blues-rock path.

"I play traditional because it's deep. It's got deep feelings," Downchild says. "When these guys sing a line, it's like there's something there, you know. There are just some things that you can't talk about. Some things just get to you so bad, you just don't want to talk about it. But those things have to come out. They come out in music."