That's what Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski told Scene last fall. It's the way everyone talked about Carlos Boozer, the kind of guy you want marrying your sister.

In the real world, it's not unusual to find people who are bright, well-mannered, warm, and gracious. You'll find them laying brick, coaching T-ball, behind a bar, serving spaghetti at the parish fund-raiser.

Yet nature has a way of cursing the extraordinarily gifted. Think of the eminent scientist who can't clasp the concept of bathing. The software wunderkind who can't get a date. The presidential aspirant, so brilliant in manipulating human nature, who can't throw a ceremonial first pitch without two-hopping it to the catcher.

Professional athletes are more cursed than most. When you're reminded of your greatness from an early age, and you're eventually paid millions as testimony to this truth, you needn't worry about acquiring the normal skills of human survival -- things like smarts, humility, or an intimate relationship with reality. Self-delusion is a job requirement.

It's why the Detroit Pistons' Rasheed Wallace can make $17 million and still whine about working on a plantation. It's why the NBA union decided to throw a $1,000-a-ticket all-star benefit for striking players. When the sun and moon orbit around your head, it's not hard to convince yourself that autoworkers and receptionists will seek to comfort those starving on an average salary of $4.5 million a year.

Which is what truly made Carlos Boozer unusual. He was a stand-up guy in a field where so few tread.

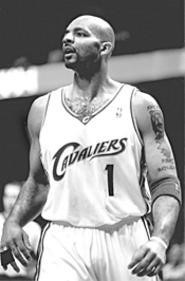

When we last left our hero ("Meet the Cavs' Best Player," November 5), Scene writer Erich Burnett was confronted with a gushfest.

General Manager Jim Paxson: "He handles himself like a 10-year veteran. If I had 12 Carlos Boozers, they probably wouldn't need me. He does all the right things."

Coach Paul Silas: "It is uncanny. Booz -- you don't think of him as a 21-year-old player. He's sound; he has toughness. If he says something, people are gonna listen."

These were happier times. By virtue of their own wretchedness, the Cavs had renewal delivered to their doorstep in the form of a phenom from Akron. Though LeBron aced his audition as The Next Big Thing, his miraculous drives and breathtaking passes always seemed chaperoned by three-point bricks and matador defense. Boozer remained the keel of this ship.

He was the perfect Cleveland star -- like Thome, Omar, Kosar, or Newsome -- the yeoman player, the guy who worked for a living. Not only could he light up a court; he could do it with modesty, a stout laugh, an omnipresent smile. Had he stayed, surely he'd reach the height of Cleveland celebrity -- doing GMC commercials with Big Chuck and Li'l John.

So it's easy to see why Paxson and owner Gordon Gund would trust such a man. When your job requires baby-sitting petulant children like Ricky Davis and Lamond Murray, you yearn to be in the company of goodness, to make a deal based on your word. And Boozer was the kind of guy you could do it with. Everyone agreed.

Yet Boozer had a deceptive quality. His grace and thoughtfulness made you forget he was only 22. It's a stage of human development largely consisting of oh-shit-I-can't-believe-I-did-that moments. You can look a guy in the eye and say all the right things, certain that your word is good. And you can regret it 10 minutes later, when something shinier comes along. Needless to say, $68 million's got a lot of shine to it.

There was also the draw of Salt Lake City. Though it might seem like a theme-park replica of purgatory, Boozer's from Juneau, Alaska (pop. 30,000). He's a teetotaler, a nature lover, a man of country ways. In his eyes, Utah was offering twice the money and a better place to live. Do you throw this away for something as antiquated as your word?

So Boozer went to the papers to plead his case. No, he didn't renege. There was never any deal. In fact, making a verbal agreement would have -- gasp! -- violated NBA bylaws.

Anytime someone invokes law to argue matters of honor, be assured he's lying.

Which is also the curse of a young man. Catch your kid stealing change from your dresser, and instinct tells him to lock into Automatic Denial Mode, no matter how naked his protests. It's a human feature that can only be disabled by repetitive use, which eventually exposes its uselessness.

Left in the wake were two assassinated characters. Whenever Boozer takes the court this winter, TV geeks with chemically encrusted hair will celebrate his drive, determination, and team playerocity. But they will also speak in cautious tones about his departure from Cleveland. It will all be very polite. Still, the message will be clear: The guy's not stand-up.

And after a brief respite last season, Bring Me the Head of Jim Paxson will resume playing to sold-out crowds. He will be ridiculed as naive, the moron who squandered the Cavs' rebirth. Calls for his resignation/firing/beheading have already become the city's anthem.

All this, and his only sin was to extend his trust, a big-time executive who took a shot at acting human. Maybe he is naive, but it's a far better fate than playing the shrewd businessman who has to lawyer up just to make a lunch date.

As for Boozer, he committed the sin of being 22. Time will be his cure.