This subject is dealt with from a somewhat surreal perspective in José Rivera's References to Salvador Dali Make Me Hot, now being presented by Convergence-Continuum. At times dense with beautifully poetic imagery, this production dissects a fairly run-of-the-mill couple and finds moments of genuine truth.

Interestingly, the play itself is not as avant-garde as the title might suggest. Though the beginning and ending scenes involve talking animals and a libidinous, mandolin-strumming moon, those vignettes bracket much longer middle scenes that are a rather straightforward delineation of a young couple experiencing an emotional crisis.

Gabriela has been married for 11 years to career soldier Benito, who has only nine more years till he can cash in his military pension and kick back. But the past decade has taken its toll on the couple because they were stationed in Germany, and then Benito was sent to serve in the Persian Gulf war. Sure, they boff their brains out when he comes home on leave, but Gabriela is looking for something more.

Stuck in a small house in the desert of Barstow, California, she feels deprived of imagination and wonder, so we share her dream life as her cat and a horny coyote negotiate their own love tryst, while at night, the ever-present desert moon tries to seduce her in ways far more than metaphoric. There's even a 14-year-old neighbor boy, Martin, who is disturbingly intent on "seeing a girl's thing" before too many more days pass.

Playwright Rivera's command of language in these dream sequences is both playful (the coyote tells the cat that when he does her, "Your ancestors will hear you . . . all nine of your lives will have orgasms") and lyrical, with the moon murmuring to Gaby, "I'm the only one who lies next to you in bed every night."

The words become more prosaic when Benito and his wife are discussing their difficulties, but the lines still captivate. Gabriela kvetches about the bigoted, small-minded soldiers' wives she's forced to associate with, and Benito eventually reveals the carnage he visited upon a village in Iraq. Unfortunately, these interchanges -- which take up the bulk of both acts -- include too many tonal swerves and cutbacks to build natural momentum.

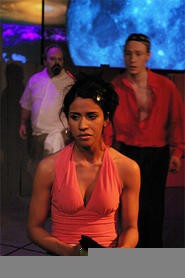

Director Clyde Simon brings effective performances out of the cast, particularly in the two lead roles. Jennifer Turpeau is thoroughly believable as Gabriela, the wife who longs for the spontaneous spark that first attracted her to her husband. Possessed of a gorgeous face and a body as hard as a sunbaked mesa, Turpeau smolders with anger and swoons under the ministrations of both Benito and the moon man. Tom Kondilas plays Benito with understatement, throwing away many lines to clear space for his character's strength to show through. His defense of his military life is compelling: "You think I'm common, but I'm not," he tells his wife. "I can survive in the middle of nowhere with a shoestring and a mirror. I defended an oppressed country. I was in history."

As the cat and coyote, Amy Bistok and Geoffrey Hoffman capture a quadrupedal authenticity as they tease about devouring each other, sexually and otherwise. And Wes Shofner, a most tumescent, er, full moon, gets off some good gibes, complaining about Shakespeare calling him "inconstant" and being referred to in the wrong gender. (It is his titillating tango and an allusion to Dalí's melting masterpiece "The Persistence of Memory" that inspires Gabriela to utter the title line.)

The side story of callow Martin (Robert Walter) trying to get into Gabriela's pants might seem a humorous diversion, but his single-minded fixation, at first harmless, turns darker toward the end. The playwright leaves that thread hanging, since it would have taken at least another act to work through those complications. But there is plenty to chew on in this production, which is enhanced by colorful screen graphics, designed by Eric Wahl, of an ever-so-slightly-changing desert and moon. Salvador, we're guessing, would approve.