On certain nights, at certain times, on certain blocks, Detroit Avenue between West 28th and 32nd is a smorgasbord of vice. The Second Police District's Vice Squad keeps tabs on the area, suppressing drug sales and prostitution as best it can. But weekends are busy, and with more than 25 burned-out streetlights and an after-midnight influx of folks seeking their own ideas of fun, Ohio City becomes the kind of playground where someone can get hurt. Earlier this month, someone did.

The stretch between 28th and 29th streets is home to three popular nightclubs. On the north side of Detroit sit the Bop Stop and Bounce/Union Station, two clubs with well-lit parking areas and buzzing security and valet details. On the south side, a seedy brown box of a complex houses a half-dozen businesses, including a diner, a rib joint, an upscale gay boutique called Dean Rufus House of Fun and a three-club combo called A Man's World/Crossover/the Shed - the former Ohio City Oasis, until 2002. More recently, the club cluster has become a multipurpose bar that hosts cheap lunches, straight country nights, blue-collar happy hours, a few thugs looking to unwind or get wound up and a base of the gay clientele who built the bar.

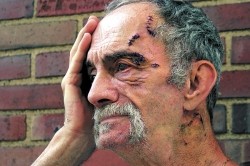

On Saturday, August 2, the latter included Jon Brittain, a noted activist in the gay community. At 64, he's seen the scene come, go and come back. That night, around 11 p.m., he stopped at the Shed bars, made the rounds, then cut across the rear courtyard that connects the block's businesses and visited his friends at the House of Fun. He left - and came back a few minutes later, gushing blood from his head and neck.

"He looked like someone had just thrown him through a glass window," says Greg Erickson, a friend of the House of Fun's owners who was there after the attack. "He was beat to hell."

Too often, the area surrounding gay clubs is a good place to be beaten and robbed: Not all the customers are openly gay - or gay at all - so a drinker who's been rolled for his wallet is less likely to report the crime. After leaving the House of Fun, Brittain had approached his car at the dark intersection of West 29th and Church streets. Two white males assaulted him and tried to steal his car. Brittain fought back but suffered a severe pistol-whipping in the process, then staggered to the House of Fun. Inside, Erickson and proprietors Dean Rufus and Tom Bayne took turns calling 911. Brittain says that at Lutheran Hospital's emergency room, the nurse on duty said that if his neck wound had been any deeper, he'd likely have bled to death. The Bop Stop, an upscale jazz club, has valet parking before shows and an off-duty policeman in its lot nightly. Owner Ron Busch says the single armed guard costs him "a couple thousand [dollars] a month. It's a cost that brings nothing to the business. [But people] expect security when they go someplace."

Down the block on the same side, the monthly security tag is higher at Bounce/Union Station, which has three or four roaming security staff inside the building, a private firm's security guard in the parking lot and two off-duty police at the door on weekends.

The night of Brittain's attack, back at the Shed - which has four bars in its three clubs - security was spread thin. Over the years, owner Richard Husarick has hired armed guards from Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority to patrol outside, with mixed results. That night, he says, the two scheduled guards never showed up, so he made some last-minute calls and got an off-duty police officer, a five-foot-something woman who's good with people and carries a gun. But any single guard would be hard-pressed to simultaneously cover the Crossover bar and the corner of West 29th Street, a block away.

And that was the point that Rufus and Bayne were loudly making to Husarick, their landlord, in a highly adrenalized, somewhat unfocused argument that took place over pools of their friend's blood.

"[Rufus and Bayne] can't talk to people," says Husarick. "They scream and get nasty."

It wasn't the first time the subject had come up. On one side of the complex are the renters and their clientele, who want a shiny, well-lit scene that's like something you'd see in downtown Miami. And on the other side, a patio and two back doors away, are the clubs' more recent patrons, many of whom just want a cheap, dark place to get their drink on.

Rufus and Bayne had complained about security before. In previous conversations, Husarick had suggested they pitch in for some extra manpower; they declined, arguing that security should be included in their monthly rent. So as Brittain's blood coagulated on the ground, the House of Fun owners and their landlord decided they'd had enough of each other.

Husarick scribbled an eviction note. Bayne and Rufus plotted their next move. The next afternoon, Erickson sent an e-mail encouraging members of the LGBT community to boycott the Shed until the landlord is forced to sell it to someone who will create a more safe, upscale atmosphere.

"I was trying to get more [security] people," says Husarick. "And [Bayne and Rufus] wouldn't pay $25 on Fridays and Saturdays. People are quick to point the finger, but there's nobody to help."

Even after the heightened circumstances surrounding Brittain's attack, all the parties involved agree: He wasn't targeted because he was gay; it was a crime of opportunity. But to Bayne, Erickson and Rufus, it felt like discrimination. The straight jazz club across the street had proper lighting and security. Why didn't their block?

"All we're saying [to Husarick] is step up and partner with people and take responsibility," says Erickson, who since has become the spokesman for the boycott. "Instead of catering to lowball street rats." Tempers cooled over the next week. The leaders of the boycott made the rounds to local politicians and activists, like the Near West Development Corporation's Bob Shores and Councilman Jay Westbrook, who agreed to fast-track streetlight repairs. Brittain, healing, carried himself with admirable vigor. Husarick rescinded the eviction notice.

Brittain and friends organized a candlelight vigil for Saturday, August 9, to let people know he was alive and relatively well. The Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender Center of Greater Cleveland visited, passing out emergency whistles and flyers with safety tips. Husarick had two off-duty police on guard outside, with two volunteers to walk customers to their cars. Rain and an early start squashed the vigil, but nobody took a beating that night.

Erickson acknowledges the increased security but expresses concern about whether it's a permanent fix or a temporary public-relations measure. Husarick says his business wasn't down for the first weekend of the proposed boycott. He says the House of Fun proprietors have offered to buy the building in the past; from one perspective, the hasty call for a boycott could be seen as a land-grab.

Regardless, Erickson says the most important point to learn from Brittain's attack is that it's no longer 1950, and even if gay bars are never in strip malls next to Applebees, they don't have to be in dimly lit back alleys either.

"It's 2008," says Erickson. "The gay and lesbian community has come a long way. We don't have to go to the worst areas in the worst neighborhoods. It's time for business owners to step up to the plate."

[email protected] In the August 6 issue, we promised a follow-up to "Waste Not," about recycled energy technology, in this issue. Unfortunately, that story had to be delayed. Look for it next week.