About halfway through the Pro Football Hall of Fame's layout — just after the exhibit that pays homage to the first century of the game and just before the solemn, reverential space that houses the inductees' bronze busts — there's a room. It contains no memorabilia, and it's a little antiseptic compared to every other room in the HOF. In fact, it feels a little like a classroom: white walls, rows of chairs facing the front, a long table.

Functionally, that's exactly what it is: a classroom.

Once an hour, two older men with white hair and white gloves unlock a trunk and haul out a handful of the hall's most unusual objects. Between their appearance and generally jovial nature, the guys come off like a pair of pigskin-obsessed Santa Clauses.

Today, they bring out a heating coil that was once buried beneath the turf at Lambeau Field. They explain that it was condensation from the overheated and busted coils — not precipitation — that caused the perilous conditions of the 1967 championship game, commonly known as the Ice Bowl. The Santas retrieve a copy of one of the earliest contracts signed by a professional football coach (Ben E. Clark in 1910) and share his meager compensation: $2 a week plus a jersey. There's a T-joint of an old goalpost from Municipal Stadium, back when they were on the goal line and any pass from inside the end zone that hit one and fell incomplete resulted in a safety.

There are shoes from the movie Leatherheads, an elevator panel from Three Rivers Stadium (as the story goes, Steelers owner Art Rooney was in the elevator on his way down to the locker room to comfort his players on losing a 1972 playoff game and missed the Immaculate Reception), a lucite face mask, a piece of the Silverdome's roof and a very primitive nose guard. Each item has a story.

You're probably wondering why these gems are locked away in a docent's trunk and not on permanent display. In fact, these relics represent a very small sample of the HOF's 10,000-item collection — 95 percent of which, the jolly volunteers will tell you, resides in the basement.

In 1963, when the HOF first opened in Canton, two buildings boasted 19,000 square feet of display space. In 1971, a third building was added, bringing the total to 34,000 square feet. By 1978, it climbed to 50,500, thanks to more expansion. Today, the Hall of Fame has about 83,000 square feet to work with.

It takes every inch of that acreage to effectively and artistically display the treasured tradition of the game through exhibits and video and audio displays. That's 83,000 square feet for approximately 500 objects. Even if you're not very good in math, you can probably figure out that this leaves about 9,500 objects, not to mention millions of pieces of paper, in storage in the basement.

*****

I'm not exactly sure what I expected to see before I entered the HOF's basement to check out the archives. Images of Indiana Jones-style labyrinths and boxes danced in my head. I imagined elaborate tunnels running under the length of the hall, branching off into dozens of rooms. Maybe there'd be one for just jerseys — thousands upon thousands of jerseys from every era and every team hanging neatly in a sprawling makeshift closet. And another room for shoes. Another for jock straps. And so on.In reality, the basement where the HOF stores its collection looks exactly like what it is: a storage room. To my surprise, it's less than 1,000 square feet — an astonishing fact considering the number of objects it houses.

There are rows of shelves, file cabinets, tables and some spacesavers like the ones you see in a library. Piled in between and on top of them is anything and everything related to football — which makes the room look like a cross between an attic and a garage sale. I half-expected to turn around and stumble over a box marked "Christmas lights" or a stack of Stephen King paperbacks marked down to five for a dollar.

In a word, it's a mélange, much like the history of the game itself. And when you're in the business of documenting and preserving everything that has to do with the cultural history of the sport, you're bound to have some bizarre items. With the exception of a safe in a corner, there's little rhyme or reason to the collection's arrangement. Priceless sits next to worthless, timeless next to dated, game-used next to commercial, historic next to knickknack, straight-from-the-field next to straight-from-someone's-attic, fan gear next to players'.

"Anything that relates to the game, we're going to collect," says Jason Aikens, who has served as the HOF's collections curator since 1997. He tells me this minutes after we browse through a small section of a shelf that contains an empty tub of Buffalo Bills Brownie Blitz ice cream. There are also some empty Pepsi cans — in a box, presumably so they're not tossed into the recycling bin.

"We try to get a sampling of things," says Aikens. "The things we really target, though, are game-used items. I get calls [from] people [who] say they have a collection, and they want to give us their autographed football. I tell them that 5 percent of our collection is on display and of that, 90 percent is game-used memorabilia. I mean, we'll collect it, but the chances that your football [will be] displayed is small."

"It can join the wall," I say, motioning to an entire wall lined with small boxes that contain about 800 signed footballs.

"Exactly," says Aikens. "That discourages a lot of people. We try to set a rule with a lot of this stuff. We'll only collect three or four copies of something, because people will send 20 copies of a poster. Museums run into this all the time. People have a collection of, say, wood planes, and they've got 20, and you really only need a couple. [They] can really jam up your storage capacity."

Currently jamming up the hall's storage capacity: Vince Lombardi's hand-drawn plays, a Hogettes dress, a drawer filled with worthless football cards (along with some incredibly valuable cards too), a small shard of wood from some defunct stadium and Madden videogames through the years. You can't turn around without exclaiming "Is that really what I think it is?" Or "Why in the world would you guys keep that?"

*****

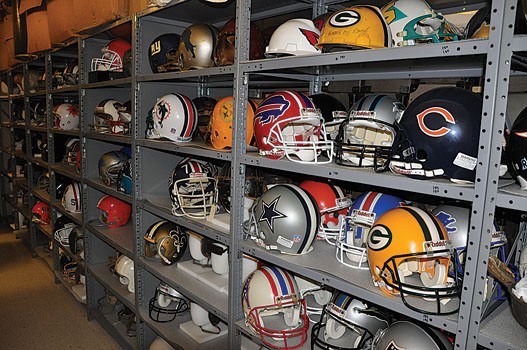

It may look a lot like your uncle's junk room, but there's some sort of organization to the HOF's basement collection. I think. There's a whole aisle devoted to helmets — from some of the earliest incarnations of head protection to relics from the World League to Mark Kelso's "pro cap" anti-concussion helmet.

Jerseys are packed into boxes to maximize space. Gloves are sorted together. So are whistles, shoes, penalty flags, consumer products, plaques, game film, ticket stubs and patches.

Most of these items can be arranged so that they don't take up too much space — except for the art. There are two massive filing cabinets, eight to ten drawers each, containing panoramic team shots from the early half of the 20th century. These are the original drawings that serve as each inductee's HOF mural.

Then there's the framed art — rows and rows of it. "We try to hang up as much as we can, because we really don't have the best art storage system," admits Aikens. So HOF employees don't have cat posters on their office walls; they have original artwork from the hall's collection hanging on them.

Not everything in the basement started there or will stay there forever. As new items are collected and space is made available, the collection is rotated. The Lamar Hunt Super Bowl Gallery will open on August 8, the same day as the induction ceremonies, so a ton of Super Bowl-related items that had languished on the shelves next to a box of Flutie Flakes cereal will now be available for everyone to see.

*****

Most of the galleries have been updated since Aikens took over in 1997, thanks to expansions and renovations. But the rotunda gallery hasn't been touched since 1994, and it still features many of the same artifacts that first appeared there in 1963. "A lot of the cases need to be updated," says Aikens. "But people really seem to enjoy it, and it could be years before plans are finally approved."

The hall is also planning more traveling exhibits that will allow some of its collection to be displayed in other museums. The Pro Football and the American Spirit exhibit, which celebrates the sport's response and role during times of crisis like WWII, is now on tour. The African American Experience in Football will be moving through the country this winter.

"It's another way we can get our collection out of storage and in front of the public," says Aikens. "We have always loaned our pieces out to other museums and institutions, so it's not like it's locked away."

On the day of my visit, there's a large cardboard box holding some shoulder pads and other equipment waiting to be itemized and inputted into the hall's computer database. It was sent by Randall McDaniel, who will be inducted into the HOF this year along with Rod Woodson, Derrick Thomas, Ralph Wilson Jr., Bob Hayes and Bruce Smith. Helmets have already been delivered. Boxes similar to McDaniel's will soon arrive containing donated items from the other enshrines.

Between 500 and 600 objects turn up at the HOF every year. Some are more important than others, but they all arrive via the same avenues. Players send stuff to the hall — uniforms, gloves, shoes, socks and other equipment — after a record-breaking performance or after they retire. The NFL and its teams pass along mementoes when stadiums open or are torn down. Relatives who inherit items from family members who were involved in the game send things (Anne Marie Bratton recently donated dad Pete Rozelle's typewriter). And fans and collectors — lots of them — call the hall, offering everything from empty pop cans and ice-cream cartons to priceless, one-of-a-kind artifacts.

But there's been a marked shift in the HOF's curatorial vision since the mid-'90s. With the exception of things like books and magazines, the nonprofit doesn't purchase items for the collection. But over the past decade, it's been more active in seeking out desirable and valuable pieces.

"When we first opened, there really wasn't a market for this stuff," says Aikens. "We always actively sought out programs, newspaper clippings, books, magazines and media guides. But the staff would just wait for the phone to ring to get artifacts. As the collectors market opened, and as these things became really valuable and the prices started going up, we started seeking out different things."

The hall got a call during its first year or so from a woman in Pennsylvania who said she had Jim Thorpe's college sweater and asked if the new museum wanted it. Of course they did. They asked if they could pick it up. Sure, the woman said, but her dog was laying on it right now. Turns out the dog used the sweater as both a bed and chew toy. (The sweater — which is ratty, faded, torn and shredded down the center where the buttons should be — still greets visitors from a glass case in the rotunda gallery.)

Not every acquisition has such a happy ending. There's a whole section of boxes containing only jerseys. Name a football great, and the HOF probably has his jersey among its collection of 600. When the Browns left town in 1996, the team sent over everything they could possibly find. Everything. "We were looking at these players and their names, and we had never heard of them," says Aiken. "We had to go look up who these guys were. Turns out, they were practice players. They never made the team."

The jerseys, like the players who wore them, are probably destined to the same fate: part of history, part of the collection and given equal status down in the basement with the Montanas and Unitases. But they'll probably never make the trip upstairs.

*****

During Pro Football Hall of Fame tours, volunteers will brief you on a handful of the hall’s favorite objects from its massive collection that aren’t on display. Here are a few of my favorite finds now gathering dust in the basement.

-- There’s a leather mask — an early attempt at facial protection in a football helmet — that comes from a semi-pro team called the Cleveland Skeletons from the 1930s. The donor told the Pro Football Hall of Fame that the eyeholes were circled with glow-in-the-dark paint, presumably to intimidate opponents. One of the few photos of the entire uniform shows that the Skeletons took their name to the extreme, wearing outfits bearing a skeletal bone-structure design. The team eventually quit wearing the mask, probably because it became cumbersome and uncomfortable after players started sweating.-- When Three Rivers Stadium was torn down, all the AstroTurf was being tossed. Franco Harris asked the workers if he could have the swath of green where he caught the Immaculate Reception. They happily obliged. Harris donated a chunk to the Hall of Fame and used most of the rest to carpet the inside of his front porch. Puts that fake-grass stuff you bought at Home Depot to shame, doesn’t it?

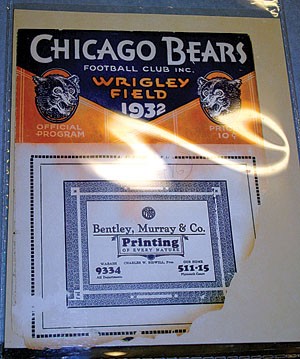

-- A complete collection of programs from every NFL championship game is rare — but not super rare. One private collection sold for a good chunk of cash, so the HOF moved its collection into a safe. But theirs is different. As far as they know, they own the only program from the first, albeit unofficial, playoff game. In 1932, the Chicago Bears — who donated the program to the hall — and the Portsmouth Spartans wound up tied at the end of the regular season. The solution to break the tie was simple: Play another game. The program contains burn marks from a fire at the Bears’ facility.

-- Look in the corners of the end zone and you’ll see a remarkably simple yet important object. Orange pylons are now taken for granted, but back in 1962, they were making their first appearance in the game. The original prototype — used in the 1962 Hall of Fame game between the New York Giants and St. Louis Cardinals — was designed by Bud Shopbell. That prototype looks very much like the ones used today, except for some cracking near the base. Periodically on display, it now sits on a bottom shelf in the basement awaiting restoration after too many visitors bent it.