If it seems you've seen a lot of plays and movies about soldiers and the frequently invisible destruction that combat has imposed upon their psyches, you're not mistaken. From the former warrior in The Best Years of Our Lives in 1946 to the PTSD-infected soldiers in Stop-Loss in 2008, and from Sophocles (Ajax) to local playwright George Brant (Grounded), many writers have explored the well-trod territory of war trauma.

The ancient Greeks called it "divine madness," while troubled soldiers from World War I were said to suffer from "shell shock." In these enlightened 21st-century times, when America is in a constant state of war with someone somewhere, some of our combatants come back tormented by "post-traumatic stress disorder." That antiseptic term, usually shortened to PTSD, attempts to make the horrific and unspeakable just banal and clinical.

In Boogieban by D.C. Fidler, now having its world premiere presentation at None Too Fragile theater in Akron, there is banality present. But while it starts slowly, this two-hander builds inexorably to a climactic scene that is so emotionally wrenching you feel it in your bones.

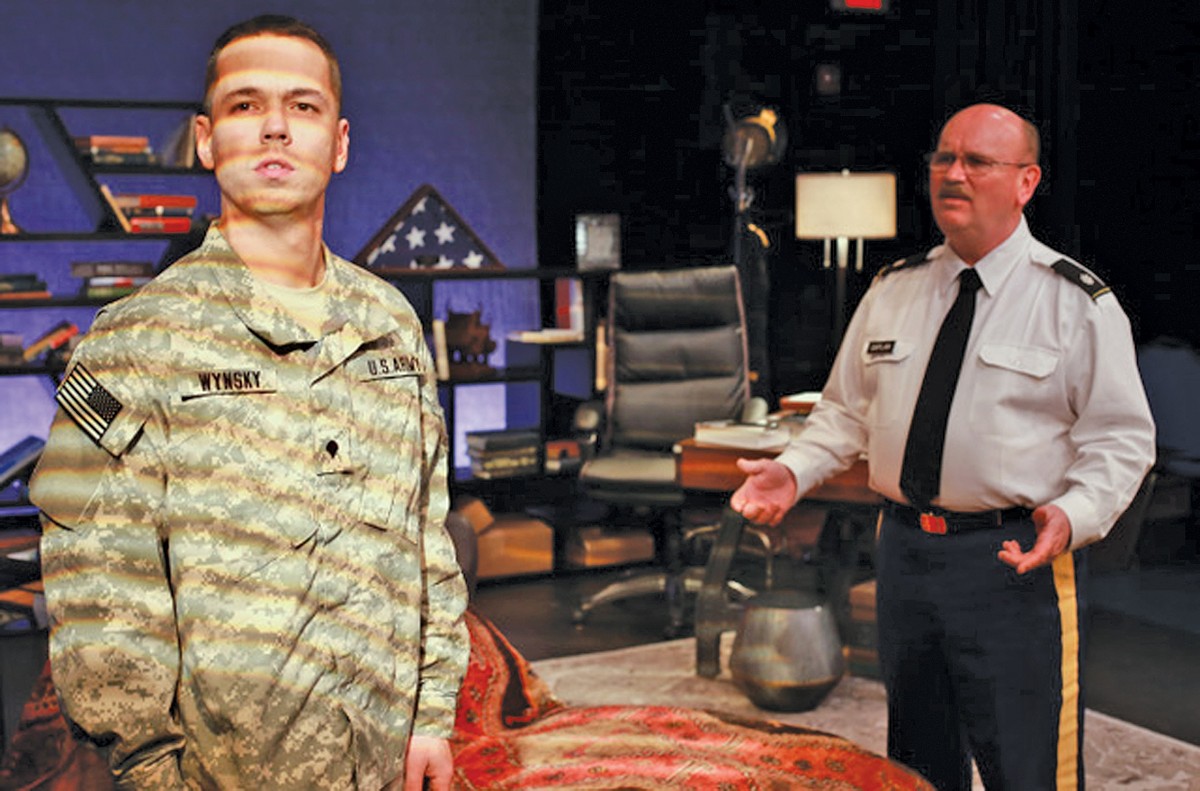

We are in the office of a military psychiatrist, Lt. Col. Lawrence Caplan, who is packing boxes and getting ready to begin his retirement. But he has agreed to see one more patient, Spc. Jason Wynsky, who suffered from PTSD from his posting in Afghanistan but now seeks a clearance to return to his unit. Once they start talking, the shrink gets intrigued and wants to conduct further interviews with this young man who clearly has demons in hiding.

For the first hour or so these two fence with their words, as Wynsky —who always wears the dogtag of one of his buddies, Josh — tries to ruffle the doctor's professionally placid demeanor. Clearly, Caplan has seen all these defense mechanisms in his long tenure, and he bats them all back like Rafael Nadal volleying tennis balls with a high school kid.

The playwright of Boogieban, referred to as Dr. Donald Fidler in the program, taught cultural and clinical psychiatry for many years at the University of North Carolina. And his expertise in the field of psychiatry shows, at times a bit too much, as his two characters vie for dominance in the confines of Caplan's book-riddled office.

At least, the office is supposed to be stuffed to the gills with various scholarly and other volumes. Unfortunately, director Sean Derry, doubling as set designer, has not found a way to capture that aspect of Caplan's environment. The shelves on two walls of the small space display a rather artful scattering of only a few books. This look seems more appropriate to an Architectural Digest photo spread than the book-hoarding, military man-cave where an officer might be hiding his own problems in the camouflage of other people's case histories.

While Derry's scenic design may slightly miss the mark, his management of these performances is right on target. Indeed, as the play progresses and we learn more about Caplan's life — his shocking experience in the Vietnam War as well as his own son's death in battle — the juxtaposition of these soldiers from different generations adds psychic heft to the proceedings.

It all comes to a devastating head when Caplan intentionally triggers a flashback in his patient, and Jason relives every moment of the tragic, life-changing event in Afghanistan that has tormented him ever since. Lighting designer Marcus Dana and sound designer Brian Kenneth Armour combine forces to make this segment of the play land with enormous power, when we learn what Jason did during a fierce firefight.

But most of the credit goes to the actors, Travis Teffner as Wynsky and David Peacock as Caplan. They exhibit a bracing focus on what their characters do and not how they feel. Or, in the words of the acting coach Mark Westbrook, they decline the temptation to "disappear up their own emotional sphincters." As a result, the sometimes desultory conversation early on pays huge dividends when the real shit hits the fan.

In particular, Teffner shows the youthful, brazen confidence of a man who is trying to fit himself with a mask of artificial assurance. Peacock matches that by showing him how an older man, quite accustomed to the wearing of masks, can manipulate his own surroundings. Up to a point.

As is often said about warfare, it's months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror. Those are the moments that can distort the lives of those who serve, in ways that the rest of us can only imagine. And that is where this play reaches us, at its most visceral level.

At the end, playwright Fidler crafts a lovely denouement expressing the eternal bond of all soldiers: I'm there for you, you're there for me. Even now, when our Commander in Chief is a person who has said his efforts to avoid acquiring STDs was his "personal Vietnam," this is meaningful.