Hunter Toth is excited. "I've got to tell you, I'm so happy you're writing this story because it's a struggle to get these points across to people who don't understand what goes into the cost of a menu item," says the chef and owner of Hook and Hoof restaurant in Willoughby. "I don't think a lot of people realize that they're paying for so much more than just the food."

It's easy to stare a meatball in the eye and decry its cost. After all, what is a meatball other than a handful of ground beef, and we all know what ground beef goes for down at the Piggly Wiggly. What should be (but oddly is not) obvious is that the cost of ingredients is only a fraction of where the money collected for a dish ends up. There's labor, rent, build-out, property taxes, insurance, utilities, linen service, glassware, cleaning supplies, payroll taxes, credit card fees ... you get the idea.

"When we wrote our business plan, we knew that we'd be servicing Willoughby in a finer-dining setting with good wine service, good cocktails and all the things that come with it," Toth explains. "That means you have to buy good glassware, certain ice cubes, nicer uniforms for the staff to wear. You pay for all these things to create a comfortable, more high-end experience for your guests."

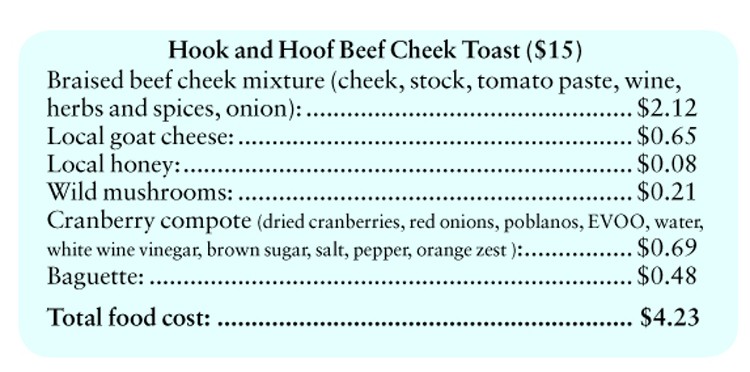

One of the most popular starters at Hook and Hoof is the braised beef-cheek toasts, a delightful dish consisting of toasted baguettes capped with supple shredded beef set atop a thin schmear of tangy goat cheese and gilded with poblano and cranberry compote. At first blush, $15 might sound like a lot of dough for beef cheeks, a so-called "off cut."

"Most people know that filet, caviar and truffles are expensive, but people look at beef cheeks as cheap peasant food," the chef explains. "What they don't understand is that to make that meat tender and delicious requires a six- to eight-hour braise and results in 25-percent loss in fat, sinew and other trimmings."

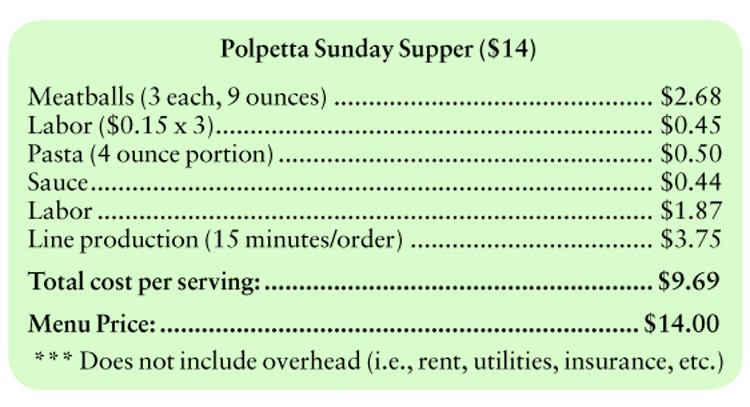

Chef Brian Okin fields similar lamentations about the price of food over at his Rocky River meatball emporium Polpetta. A popular gripe on Yelp goes something like, "$14 for three little meatballs?!"

"I think it's a perception issue," he says. "Because the Sunday Supper is something they can make at home, people assume that it should be less expensive. What they don't realize is that we're buying quality meats from independent local farmers. This is not boxed meat coming off the back of a Sysco truck."

Those "three little meatballs" add up to more than a half pound of fresh, local beef. They also come atop a bed of spaghetti topped with pomodoro sauce. By way of comparison, a similarly sized hamburger and fries at Cheesecake Factory costs $13.

In addition to the cost of ingredients, that $14 gets spread across all of the aforementioned costs of doing business, as well as to cover losses from waste, comps, mistakes, theft, broken glassware, inefficient labor and spoilage.

"This is a very unpredictable business," Okin notes. "If we have big dips in business, we could lose product to spoilage."

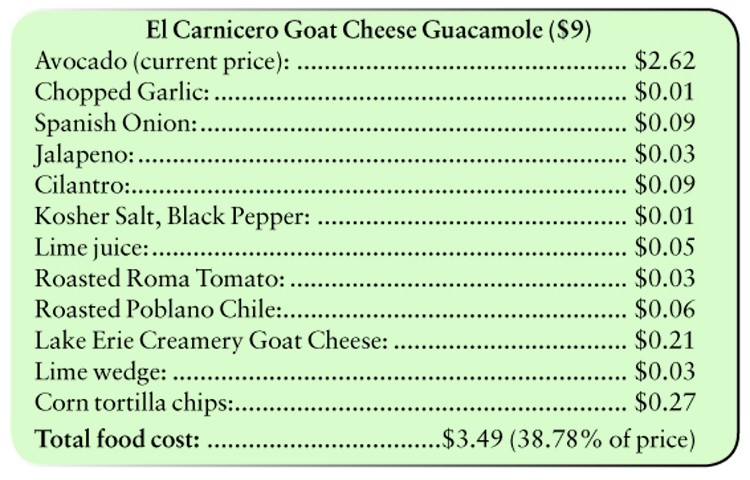

Combined, the restaurants of Momocho and El Carnicero fly through approximately 2,500 avocados per week, which is not at all surprising if you've ever dined at either restaurant. Even the casual observer can see that nearly every diner begins his or her meal with one or more of the guacamole dishes.

"By far our guacamoles are the best sellers on the menu," says owner Eric Williams. "We built the entire dynamic of the restaurant around our atmosphere, craft margaritas and gourmet, unique guacamoles."

Depending on the price of avocados, the popularity of guacamole can be very good news to Williams' bottom line or not so good news. That dish's food cost percentage (cost of ingredients divided by the menu price) generally fluctuates between 40 percent, when perfect-but-pricey avocados from Northern California are in season, down to 29 percent in peak Mexican Hass season. But external factors can send that percentage soaring to as high as 50 percent, reports the chef.

"As a matter of fact, I just received notice today that avocado prices will rise and possibly become out-of-stock as a result of a labor strike and cartels in Mexico causing big problems," he says.

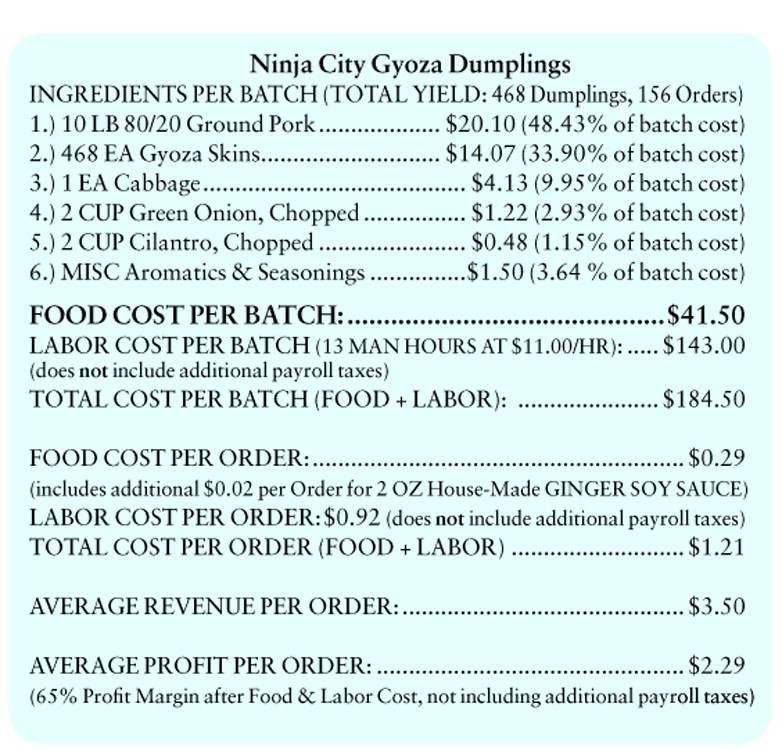

Ninja City in Gordon Square is Bac Nguyen's third bite at the restaurant apple, so he fully grasps the importance of scrutinizing every penny that goes to food costs, labor costs and every other expenditure. Given that the most popular item on the appetizer section is the gyoza, one would expect him to try and boost his profit margins by trimming his labor costs. One of the simplest ways to accomplish that is by utilizing a pre-made product.

"Labor is the bigger cost," he says. "Plenty of restaurants sell pre-made dumplings, which cost a little more but will save you money on labor. There's a fine line between efficiency and taking shortcuts. You try to do things as efficiently as you can, but I think people can taste the difference. I have not found a pre-made product out there that tastes the way I want it to."

Instead, Nguyen's prep cooks fill hundreds of wrappers by hand with ground pork, minced vegetables and aromatics before steaming and searing them.

"The gyoza dumplings are now our top sellers among the 'little bites' at Ninja City," Nguyen reports. "They recently surpassed the spring rolls as the most popular."

Most diners know that the easiest way for a restaurant to boost razor-thin profit margins is by selling booze. Every beer, wine and cocktail that is ordered goes a long way toward making a restaurant successful. But even those places that seem, by all outward appearances, to be thriving financially are very likely simply affording a modest living for the principals.

"I think that when we're busy, people assume we're killing it," says Toth. "We're probably driving Mercedes and have huge homes in high-class areas, when it's literally the opposite. We're not a sinking ship by any means, but there is such a perpetual loss of money that you have to keep guests coming in, know the costs of goods, and charge people properly."