Doug Dieken is in the middle of talking about why he's happy he waited until after his playing days were done to start a family.

"You wouldn't have time to spend with them," he says slash grumbles. "You come home miserable, all beat up from the game ... It just wouldn't be fun."

He's perched sideways in the front booth at the West End Tavern, a place where he seems to know everyone from the kitchen staff to other customers by name, with his right leg up and extended on the bench, because these booths were not otherwise constructed to accommodate the frames of men like Doug Dieken, whose 6-foot-5 build — a "soda machine" as Tom Withers of the Associated Press described it — remains, against all efforts of time, decidedly athletic and imposing. The extra leg space also doesn't hurt for twin stems centered on two artificial knees.

Anyway, Doug sort of abruptly stops his familial reverie and stares at the television above the bar. If we didn't know better, the adjustment would have been a pretty clear social cue that we'd lost his attention. After all, it was just The Price is Right, and the sound was off, and closed captioning was definitely not on. But we know better, because Doug is an attentive and generous conversation companion. So we had a hunch of what was coming next.

"I'm watching Drew Carey," he says, letting a beat go.

"He used to be a waiter down at Sammy's, down in the Flats. I had to do some roast or something, and there was this girl I knew, and she said she had this friend who was pretty funny, he writes some stuff. I go, 'Oh?' I mean, sure, come on. So she gives me four pages of stuff and it's really, really good, really funny. I said, 'This is good shit. What's your friend's name?' And she says it's Drew Carey; he writes stuff for Lanigan too. Oh neat. Well, I never thought anything of it, but then he did that TV show and I'm like, 'Hey, that's the guy!'

"This one time I was down having dinner at Sammy's, and this was before the show, and he was our waiter. He screwed up our order. So anyhow, years later, someone sends me this video. It's Drew talking about being a waiter and serving me and screwing up and being embarrassed because I was one of his favorite players. He's a good Cleveland guy.

"A couple of years ago, we were out in Seattle and we weren't doing very good. [Eric] Metcalf was there. They're good buddies, he and Drew. So [during the game] I nudge him and say, 'Hey, can you call Drew and see if he has any material for the second half?'"

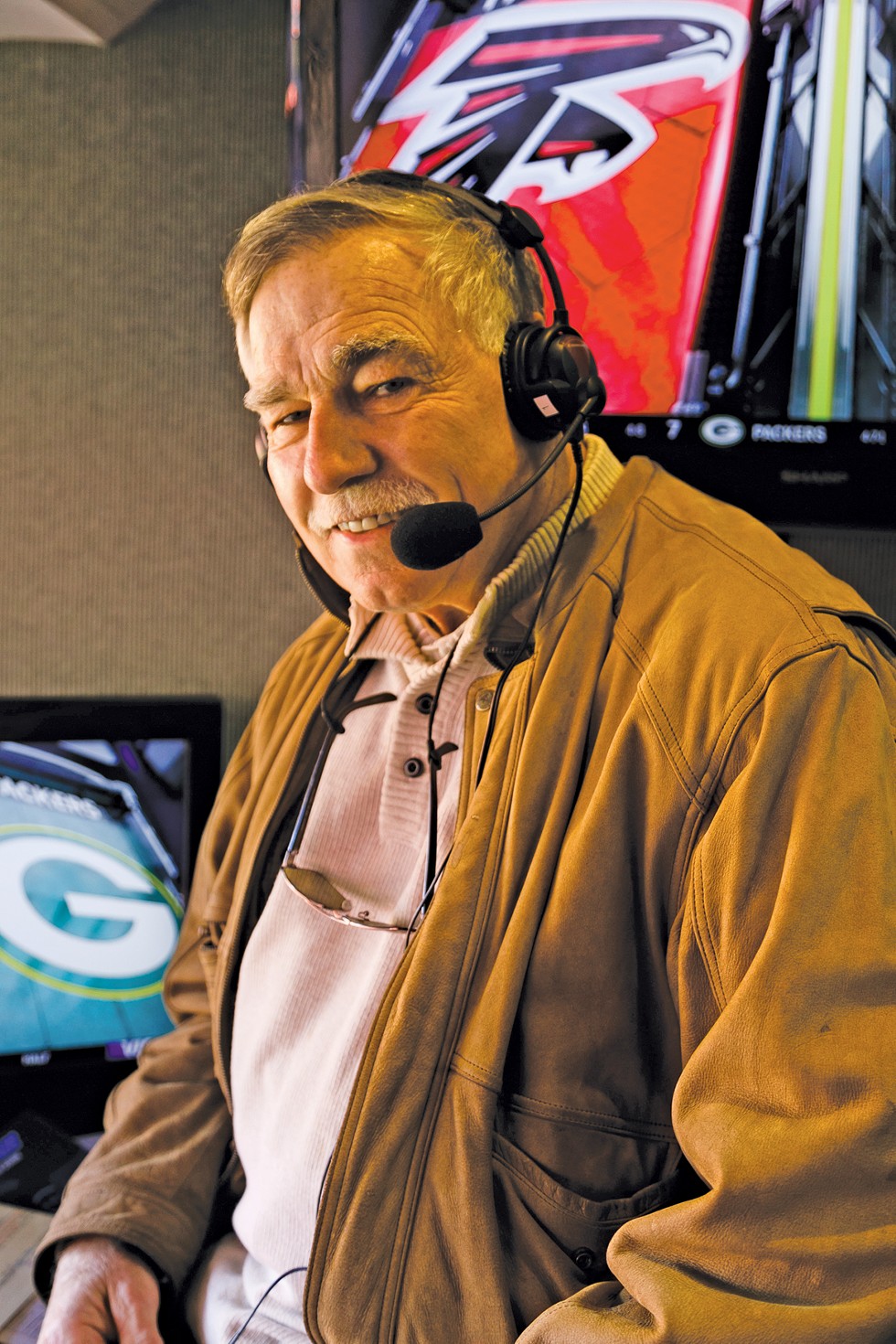

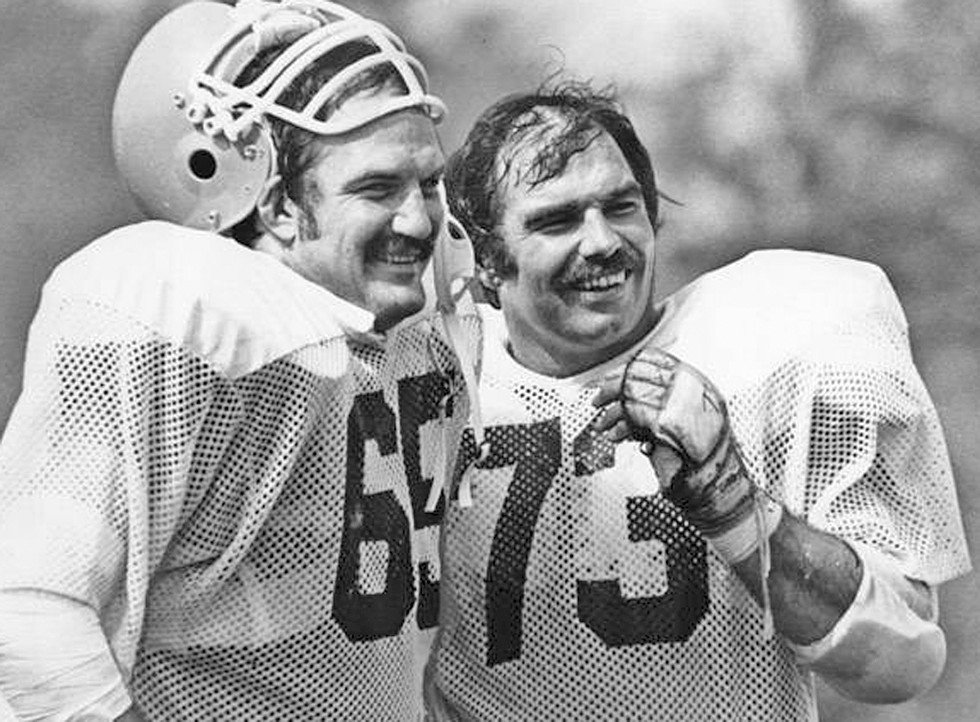

This is sort of how it goes with Doug Dieken, the Iron Man of Orange and Brown Iron Men, on not one but two fronts. After playing 14 seasons for the Browns (1971 to 1984), a stretch during which he played every single regular season game (203 consecutive games with 194 consecutive starts), he immediately stepped into the Browns' radio broadcast, where he remains to this day. During that stretch, which now stands at 31 years, he's only missed two games — one in 1989 after his mother died (incredibly, he lost his father 10 days later but worked the game after that) and one when the Browns visited London and a doctor recommended he skip the lengthy road trip due to a health issue. And those three seasons when the Browns were in limbo in the post-Modell pre-expansion years? He spent those working as an ambassador for the Cleveland Browns Trust. All told, Doug Dieken has spent 48 of his 69 years on this earth working, in one of three capacities, with honest effort every day, for one franchise. There are Browns players in recent memory who didn't spend 48 of 69 days doing something positive for the team.

But here's Diek, beloved Diek, steadfast Iron Man Diek, a man who one beat reporter described as the "A-list Celebrity" at a training camp, even when that training camp included No. 1 draft pick Baker Mayfield; the man who has almost definitely seen more Cleveland Browns games live than any other human being; the voice that, with a grunt and a grin, enters tens of thousands of homes and cars and offices and garages sixteen Sundays a year to bring you the action of your favorite football team.

And, somehow, possibly out of narrative necessity or a gap in Scene's cover story schedule, there's a sense that Doug Dieken has not gotten his due. At least not for his second career and, in the larger picture, not for his very existence and lasting legacy as one of the most/best/quintessential Cleveland people of all time despite not being from here.

Part of that can be ascribed to the modern consumption of football — on social media, on NFL Red Zone, on phones and on online streams pulled from Reddit — that has naturally displaced radio. Part of that can be attributed to the fact that Doug has stuck around, which is usually a reason for people to pay attention, but in the case of the Browns might have been overshadowed by a near hourly breaking news cycle featuring some calamitous off-field incident, trade, front office move, coaching decision, horrible draft pick, baffling draft pick, motorcycle accident, domestic stabbing incident, insane trade, staph infection, team lawsuit, suspension, executive vice president dismissal, interest by the Feds in the owners' other business, gradients of orange, wordmarks, stadium renovation talks, field-adjacent vulgar chastisement of a female ref by a team employee, 0-16, 1-31 ...

This, if you know Doug Dieken or listened to a broadcast or interview, is where he would groan. And then he'd probably tell a joke, and then he'd bring up some story whose undercurrents brim with optimism and humor.

Doug has a locker full of them, and they serve as a road map of a life lived, and a life lived well. They come out of nowhere sometimes. Like in natural pauses in our conversation, the points when an interview subject would normally quietly wait for whatever dumbass question was coming next or pull the string a little further on something that was already on the table. Doug has the greatest hits pulled up and ready to go though, and when pauses arrive you can see him punching B-13 on the jukebox — that's one the folks always love — and once that one's over we're on to D-5 and then A-12. And it all feels random and part of a performance, but it's not. It's just Diek, and these stories are about people or moments that he loves, and he's sharing them with you. And through the one-liners and Glory Days tales there emerges a central worldview and pattern that go a long way toward explaining who he is as a person. And, if that doesn't turn out to be the case, no one ever got hurt hearing more Diek stories.

***

"One of my teammates [at the University of Illinois] and best friends was this guy who was a walk-on," Dieken says. "Never played football in his life, but he ended up earning a scholarship, which kind of tells you where we were as a program at that time, but it also tells you something about this guy.

"Well, one day, I'm over working out in the off-season and I get in my car to go to lunch, and on the radio they say President Reagan has been shot. I go to Bucci's in Berea and I'm watching and they're showing the video and, holy shit, that's McCarthy. Tim McCarthy. The walk-on, my friend. He was a Secret Service agent and he was the guy that jumped in front of Reagan and got shot. You think, oh Christ. You wait to hear the news. Well, he's gonna be okay. I wait, he recovers. Then I get this T-shirt made. It said Tim McCarthy Fan Club and it had a big bull's-eye in the middle. So I send it to him. President Reagan transferred Tim to Chicago, and then he got transferred back to Nancy's detail, and one day he's on this ranch with the President who's wearing some generic T-shirt. Reagan says he feels stupid wearing this thing. Tim says, 'You think that's bad?' And he pulls up his shirt and underneath he's got the fan club shirt. 'Where'd you get that?' Reagan says. Tim says a college buddy got it for him and Reagan says, 'You got some sick friends.'"

Pranks, ball-busting, one-liners — it's how Doug Dieken brings you into his world and shows that he likes you. If he's not having a laugh with you, it's a pretty clear indication of where you fall in his regard. If you mention someone and he calls them a "beauty," that's Diekenese for someone who is a worthy ball-busting opponent. If you mention someone and he says they're a good guy, oftentimes that'll be followed with a note that said person is also easy to make fun of, which is a high compliment, because Dieken himself is easy to make fun of and he's just looking for someone to join him on his level. It's affectionate ribbing, not hazing, and it comes from the sweetest part of his heart. "You're not going to waste time on some jerk you don't like," he says.

It shows up privately, and publicly. Like the time in 2007 when the Browns were in St. Louis.

"Diek would tape a little introduction for the official broadcast and he'd write out what he was going to say on a legal pad. Old-school as it gets," said Zac Jackson of The Athletic Cleveland, who worked for the Browns at the time along with his podcast partner and Fox Sports Ohio Indians in-game reporter Andre Knott. "So this one, Diek gets on the air and says, 'Welcome to St. Louis, where Andre Knott saw the arch and ordered a Big Mac.'"

His quick wit is also aimed straight at himself, his self-deprecating sense of humor part and parcel of his personality on and off air, a key component of his longevity and success as a broadcaster and a main reason he was and remains in demand on the banquet and Browns Backer circuit. In earlier years, those events were both something Dieken didn't mind doing as well as a source of supplemental income, at a time when player salaries meant off-season jobs and basically any local commercial offer that came their way, especially during the Kardiac Kids era when anyone associated with the team was sought after to endorse anything and everything.

(Dieken spent one early off-season substitute teaching back in his hometown of Streator, Illinois, a place where "meeting up to fight with the guys from the town 16 miles away" qualified as having fun on a weekend. He was largely assigned the "knuckleheads" and spent one class making a kid do pushups and situps as punishment and one other subbing in for the German teacher despite knowing little German. "At the beginning of training camp they asked what you did during the off-season and I thought I'd be funny so I said I taught German," Dieken says. "They put it on my bubblegum card.")

Why show up and bore the people though? They know who you are and what you've done. And why, if you're a ball-buster and could-be amateur comedian like Dieken, wouldn't you turn something as simple and straightforward as the Our Lady of the Wayside benefit into a late-night roast?

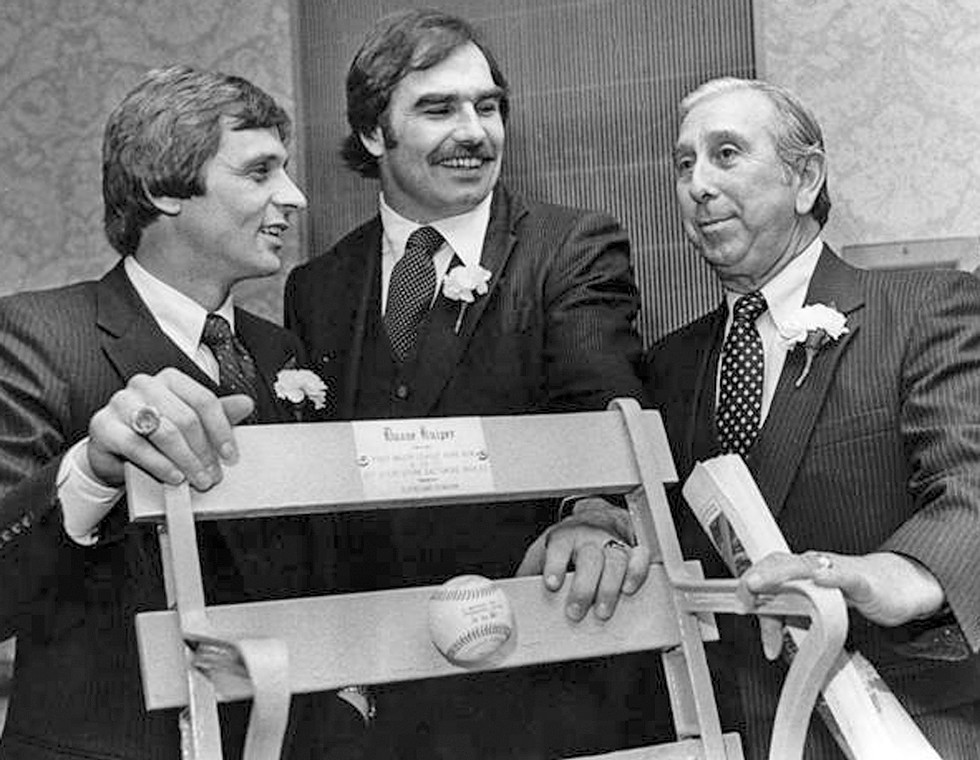

"I'd rather laugh and have fun than just sit there. The first year I did it [Duane] Kuiper was there," Dieken says. Kuiper was a pal and a lockermate at the old stadium — Dieken says he could pick their locker out from any other, despite no nameplates on the wooden frames, because of the ashtray they shared — and a cosmically perfect foil for the left tackle: Kuiper had just one home run in his career and Dieken had one touchdown reception. "So I get up and start taking shots at Kuiper. The next year he got the message and came back at me."

The Doug Dieken and Duane Kuiper show became a fixture at the event until Kuiper was dealt from the Indians to the San Francisco Giants in 1981. The last Dieken-Kuiper affair, memorialized by the late great Hal Lebovitz, includes zingers from Mike Hargrove, Joe Charboneau — "The only thing Doug Dieken can't hold is an audience" — and the two stars. Dieken: "Salute to Duane Kuiper, baseball's first designated fielder." Kuiper: "Now let's make Doug Dieken feel at home. Would you please throw your dinner napkins to the ground and move your chairs back 10 yards."

(Dieken's propensity to hold was later celebrated by a friend at the Bay Village service department when Dieken retired, with a yellow line painted from his house down four or five blocks of Lake Road, totaling the number of holding penalty yards he incurred during his career.)

Though the banquet circuit has slowed, he still does plenty of speaking engagements and not much, as you might imagine, has changed.

ESPN Browns reporter Pat McManamon remembers an event they did together in Brunswick one year.

"It was a pretty big crowd and as is his custom, Diek taps the mic and goes, 'Testing, one, two, three," McManamon said. "So I open and I say, 'Thanks to whoever in the front row helped Diek get to three. Then I hear him in the background, 'Oh, okay, that's how it's going to be.' For the rest of the talk he didn't get through 12 words without insulting me. He pounded me into the ground. He doesn't retaliate; he escalates."

Like when, way back in the day, Dan Coughlin wrote one of his many Plain Dealer columns about Dieken. This one centered on the oh-so-lonely life of the poor bachelor living out on the lake by his lonely self with no friends. Dieken, whose number was listed in the phone book, was deluged with calls from strangers.

"Okay, Danny, that's how you want to play this," Dieken says. "So I change my answering machine to say, hey everyone, me and Danny are still friends and, to show you we're still friends, you should know he's having a party on such-and-such day at his house, and I gave out his address and said Danny is a big collector of empty beer cans, so if you have any laying around make sure to bring him to his house."

When Coughlin got married, Dieken, who knew where the key to his house was hidden, installed mirrors on the bedroom ceiling and filled his bathtub with goldfish to toast the nuptials.

"I didn't know it leaked though," he says. "So when he got back from his honeymoon it wasn't real pretty."

"Part of it is the game will burn you out," Dieken says, "if you don't have fun with it. So you have fun at the expense of your teammates and friends; you see who you can pull a practical joke on. Some of those stories, we can't really tell them here, even though it's Scene. They'd fit in real well there, though. There were a few of them that were classics ... Eh, we'll just leave those out."

His friends and colleagues have some, of both the on- and off-the-record variety, and they're hilarious and charming — but without fail, what they're more interested in sharing are anecdotes and testimonials about Doug Dieken, the absolute class act and friend. The visits to the hospital, the helping hand, the calls to check up, the overwhelming kindnesses.

Pat Dailey, one of Diek's neighbors and a longtime singer who performed at the islands and down in Key West, has a physical reminder of both sides.

"I had to fly to Put-in-Bay one winter," he said. "And while I was gone, he had a gravestone with a real bad poem on it — he's not a writer — and it had something to do with Jimmy Buffet being the real king of Key West. Anyway, it was in my flower garden when I got home, which was the same day that Buddy Holly's plane went down, and here's my gravestone at my house with me on a flight. Anyway, every time we came home from a night of drinking, he'd go out back and take a piss on my gravestone. But he's got a big heart, about as big as his head. He's warm and generous, he just doesn't let people see that too often."

Dieken's broadcast partner, while without any urine-tinged sagas to share, feels the same way.

"He's incredibly vigilant and caring about what's happening in my life," said Jim Donovan. "I had a real health scare awhile ago, and he was incredible to me, almost like a father to me, and he's a great dad. When Casey Coleman had cancer and was away from us, every Sunday we were in the broadcast booth, he made sure to dial up Casey and ask how he was feeling and doing. That's the kind of guy he is. When we went to Baltimore, there'd be this very quiet message from the Ravens organization and it would filter to Doug and he would go see [Art] Modell in his declining health days. They had their differences, and the move wasn't easy on Doug, but he maintained a relationship."

(They certainly did have their differences, especially in the days when Dieken was negotiating his own contract, but "I got along with Art; he was just a millionaire in a billionaire's game," Dieken says. "One of the last times I was out there and he was alive, I went at halftime to his loge to say hi. David, his son, was there, who has since passed. And I ask where his dad is. In the bathroom. I only have so much time, and the clock's ticking and I gotta get back. So I knock on the door and say, 'Art, it's Doug Dieken. You don't owe me any money, you could have come out.'")

The humor is always inextricably linked to the relationships, and Dieken has a million of them, as a teammate, colleague, friend and as a man who most clearly represents what it means to be a Brown. Forget whatever marketing campaign is in vogue in any given year under any given newly minted Vice President. They could scrap it all and just throw a picture of Dieken's face up and everyone would understand.

"This is just a guy who's been great for Cleveland, it's his home and his heart," said McManamon. "One day the city will look back and appreciate what they had for so long as a player and broadcaster."

"He's ingrained in Cleveland," said Withers. "He's more than a color guy, more than a former player."

"I can assure you, when the Browns have training camp or some event, everyone gravitates to him," said Jackson. "And whether they need him to take a sick kid around, or meet one of the big corporate spenders, or some coach's wife's dad's high-school pal wants to talk, he's there and an ambassador. You can't teach that stuff, and you can't fake that stuff. People rely on him. He's an absolute treasure and my friends and family think it's the coolest thing that I know him. Of course, the other day in Cincinnati I walked in and he was talking to a friend in the press box and I go by and he says, 'Well, good morning, bitch.' That's Diek."

***

"You're just there to laugh or fill in the blanks," Dieken says. "It's like doing one of those paint-by-numbers. [The play-by-play guy] does all the work and you just fill in some paint. I've been very fortunate to work with great guys, and Jimmy [Donovan] ... Jimmy's an immense talent. He's a fanatic about it. We used to go to Youngstown to get fireworks. So we're driving and he's listening to Wimbledon on the radio. You ever listen to tennis on the radio? You know how exciting that is? Forehand. Backhand. Forehand. Backhand. But he's a student of everything. I have so much respect for him. It's his show. I'm just window dressing."

This is Doug Dieken's answer, at least the beginning of it, to a query about his role on the broadcast and his career behind the mic. This is also how it goes with Dieken. It's always about someone else.

Jim Donovan is the reason the broadcast succeeds. Before that, it was Nev Chandler and Jim Mueller and Casey Coleman who made the broadcast sing. It was Joe Tait, who called up Dieken one day to review one of his early broadcasts to give him pointers, who made him better at his job. The fact that he landed the gig at all the year after he retired? "The timing was right. Sometimes skill has nothing to do with it," he says.

His kids, a son and a daughter, are wonderfully talented and amazing people because they have good values, they did the work, and they grew up without ever making Dieken raise his voice to them. Great ambassadors for the Cleveland Browns? Oh, the two greatest are Lou Groza and Dino Lucarelli, not him. His sense of humor? Even that he won't take credit for. That's thanks to a guy he knew in college named Paul who was the king of all ball busters.

But Dieken deserves credit for the broadcast, which is among the best you'll find in the NFL. The pairing just works, and has from the start, even though Dieken and Donovan never even auditioned together as the team was creating its broadcast roster when the Browns returned in 1999.

(Dieken had to re-audition for the job that he had held before the team left. "I did my audition with Jeff Phelps. They told you the game you'd be calling — they put it up on a TV and you'd do the game — so you could get familiar with the personnel," says Dieken. "This was before they had NFL Game Pass and stuff, but I had friends who were still coaching, and since they told me what game we'd be doing, I told a friend, 'Hey, get me a copy of that game on tape.' So, I went in to do my thing and I had a pretty good idea what every play was going to be. I looked like a genius.")

"From the very first game we did together," said Donovan, "the Hall of Fame Game in Canton, it was just two guys sitting around talking football like we had tickets to the game. It's just kind of continued that way. He takes some of the emotion out of it. I can be very emotional. He can clinically say why a play did or didn't work, or why he's throwing the ball here and not there."

Indeed, while Donovan is Chubba Wubba Hubb-ing or bellowing, "RUN WILLIAM RUN," Dieken is a counterbalance. The pair are polar opposites in the booth — Donovan seemingly running every step with Nick Chubb as he broke free on the 92-yard run, rhythmically punching Dieken in the shoulder like his arm was a video game button; and Dieken on his stool, rarely moving. And in between emotional exaltations, Diek is in the background using every bit of information he has — his 14 years on the offensive line, his hours spent talking to players in the locker room about game plans and schemes — to do exactly what a great color guy should do — explain the nuts and bolts of the game. And he does so with an economy of language and assortment of groans, grunts, chortles and laughs that qualify as an entire separate dialect.

"You always know when a bad play is going to happen, because he can see it developing," said 92.3 The Fan's Ken Carman. "That's the nuance of it. If you listen closely, you can hear him in the middle of Jim's call. He'll either exclaim a little bit if something looks good or groan. You hear that, you know."

Carman and the morning show crew at 92.3 so dearly enjoyed Dieken's guttural reactions last season that they created Game of Moans, wherein they'd play three clips of Dieken's noises to him and have him guess to which plays they corresponded. Fun, games, etc., but for Carman and Donovan, the understanding of the game behind those primal utterances is invaluable.

It's why Dieken can tell Carman the host's initial read on Joe Schobert was off-base and the linebacker was poised for big things, and he'd see it too if he paid attention to this and this and this. It's why he can direct Donovan's attention to the back corner of the facility during training camp, back where the scrubs were all gathered, and tell him to watch rookie undrafted free agent Desmond Harrison's footwork and he could really put it together and be a starting tackle in the league. It's why he can look anyone in the eye who at one point was excited that the Browns signed Dwayne Bowe and tell them it was going to end up a failure. ("You can add Kenny Britt's name there too," Dieken says.)

He's also privy to information that the rest of the media isn't, not that Dieken enjoys being called a member of the media. It's harder for him, he says, if a player he's talking to in the locker room doesn't know that he played. Not that he takes it as a personal affront — hey, you don't know what I did for this franchise — but because if they know and trust him as a former player, they're more inclined to be honest. By his estimation, maybe 75 percent of the players probably don't know he played. That number feels high. Donovan noted Dieken commands immediate respect because of his playing days. "He walks the line really well," Donovan said. "He's a friend to them, but in the right way. He's not a groupie. He can be an advisor, he can be anything they need him to be."

Joe Thomas agreed. While not every player knows, and while not every player takes the time to get to know him, the ones who do are rewarded.

"The guys love his sense of humor, his surliness," Thomas said. "They love hearing old stories. He doesn't want the cliche media answer. He's not looking for a whole lot. He just wants a flavor of what the players are thinking, some insight that might be beneficial to the broadcast. Normally you see someone from the media and you go into cliche mode, protect the team. But with Diek, he wants to develop relationships. I used to tease him, because he's in the locker room during media time, that I think in my 11 years I never once saw him ask a question."

"I would say of the information I run across, I probably eat 40 percent of it," Dieken says. "Because it's none of my business. Some of it helps me understand the big picture, so when I'm making a comment I'm giving it with some background to it. But I don't want to be a gossip columnist."

Which is a shame, because he would make a damn great one, at least for anyone interested in the unreported inner workings and palace intrigue of a place as rich with fabulous yarns of personal and professional malfeasance as Berea, Ohio. The sum total of Browns' secrets Dieken must know at this point would be enough to stop a Myles Garrett blitz dead in its tracks.

"I can't say he knows where all the bodies are buried," said Zac Jackson, "but he knows the directions and certainly has the relevant cell phone numbers."

But, as Dieken says, you don't last this long by sharing everything you know, and at every turn, when prompted to dish on this coach or that GM, Dieken chooses to take the high road. But trust that he knows, and has a good sense of whether something is going to work out or not, even if he doesn't share the information or opinion with anyone else because he's a professional, and, either way, the Browns couldn't possibly be dumb enough to really do that thing he heard about.

"I had heard about Sashi [Brown] prior to it happening," Dieken says, "but I never told anyone because I didn't think it would actually happen. I mean, I was thinking, no, they wouldn't ... "

***

"You know, I might be the only guy that took a college team out on strike," Dieken says. "We had a slush fund, but it was the previous coach's, and we were on probation all four years I was there. We were really bad (8-32). There's some 500-page book on the history of Illinois athletics and I opened it and looked for our years and it was two pages and it was titled, 'The Lean Years.'

"Anyway, the new coach got stuck with a bad time. My senior year, we were getting ready to play Ohio State, and the assistant comes up to me and says they fired the coach, Jim Valek. Well, he said he was going to be fired after the game. The boosters wanted him fired. My team isn't the boosters. So we drew up a letter to the athletic board and told them they made a mistake. I stood up and said, if he's not here on Monday, I'm not here on Monday. Anyone else with me? Thankfully, everyone raised their hands. So they had to rehire him, and the next week we were playing Purdue in their homecoming game, which would have been real ugly if we didn't show up. After the game, I gave coach the game ball and I was listening to the radio that night and I hear, 'In West Lafayette, they gave a coach the game ball.' And it was Howard Cosell. Of all the things I've done in sports, that's probably the thing I'm most proud of, because there's no loyalty anymore."

There is with Doug Dieken, and not in the conditional and temporary way most people claim to be loyal. It's not something that's convenient or easy or self-serving. It's unwavering and it's real.

It's why he was now telling a story about John Dorsey gathering all the new draftees and free agent signings for a big dinner at the stadium before training camp. Dorsey had invited eight Browns' alumni, including Dieken, to join the affair and talk to the new players. It seemed pretty unremarkable. Doesn't this sort of thing happen all the time?

"Yeah, well, not really," Dieken says. "When Holmgren was here, not that he would care, he had a guy that ran the alumni and cared about the alumni and he wanted them to be treated with respect. But then when he left, it kind of faded away. The only other time I remember doing something like that was when Bill Belichick was here. Whether you liked him or not, you knew he had a respect for tradition and the history of the game and team."

That history is intrinsic to Dieken's tandem roles as announcer and broadcaster — as Tom Withers said, "That connection between the fans and the radio booth ... people want to hear from a Browns player's perspective, especially an offensive lineman who's hit Joe Greene in the balls" — and it's something he fiercely believes when asked about who might replace him one day.

"Yeah, I'm protective," Dieken says. "There was a point in time when I had someone I kind of wanted to hand it off to if I could when the time came, but they kind of got away from the Browns."

That would be Aaron Shea, who played for the Browns and worked for the organization as a player liaison during Randy Lerner's tenure. Shea was unfortunately jettisoned by Ray Farmer.

"Aaron can talk," Dieken says. He also has high compliments for Joe Thomas, of course, who is endeavoring into media after his retirement, and Tim Couch, who Dieken recommended to do a Browns' preseason game, and Dustin Fox, who did a long stint as a fill-in sideline reporter this year after Nathan Zegura's suspension. "You got to have someone doing the job that understands the mentality of a football player, guys who can talk to the whole locker room, guys who don't see black and white, and Shea was that. I guess I just have a loyalty to guys that have played for the Browns."

Dieken, if you're wondering, is not actively pondering retirement, though, "After 1-31, it was not getting to be that fun, that's for sure.

"You want to quit on your own terms. It's like when you're a player. You want to continue to play, but you don't want to be a negative to the team. You have to be honest with yourself. Much like up there, you're seeing what you're seeing, and you're trying to talk about it, but if it gets to the point where it starts getting gargled, I hope I'm smart enough to say it's time to go. It would be neat, I've thought, if I could quit when I was 73. But I still get an offseason, so who knows."

He waits a beat.

"Although, as a friend told me, who can tell the difference?"