Between May 31 and June 24, Cleveland police received well over a thousand calls reporting nuisances and disturbances.

They handled approximately 100 calls about robberies, and 50 reporting sexual assault.

That’s not unusual for major metropolitan police departments, according to an analysis the New York Times ran on June 15.

In New Orleans, Sacramento, and Montgomery County, Md., the Times found about 4% of the officers’ time is spent on “violent crimes,” defined as rape, homicide, felony assault and robbery. For other major metropolitan departments like Baltimore, Phoenix and Seattle, they found between 0.5% and 1.8% of the calls logged in their dispatch systems fell into the “violent crime” category.

Cleveland, which posts the past seven days worth of dispatch calls on an online map, falls roughly in line.

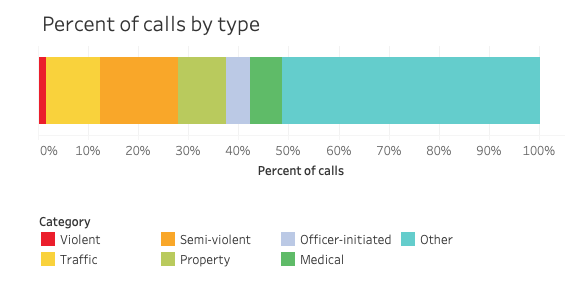

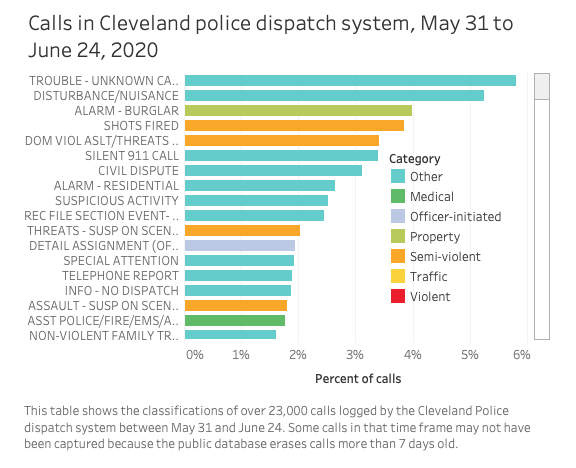

Four weeks’ worth of call data collected included over 23,000 calls. (Some calls may not have been captured due to rolling erasure of data from the public map.) Dispatch calls include calls made to 911, as well as reports from police.

Of those 23,000 calls, 1.75% of calls fell into the “violent crime” category.

Some advocates for “defunding the police” have pointed to the small percentage of police work that deals with violent felonies as an argument for shifting resources away from departments.

“[Police are] not out chasing bank robbers or serial killers. The vast majority of police officers make one felony arrest a year,” Alex Vitale, author of The End of Policing, told Jacobin. “If they make two, they’re cop of the month.”

But it’s important to note that the “violent crime” definition used in the Times’ analysis (and here, for the sake of comparison) is extremely limited. Their definition is based on the one used by the FBI for its Unified Crime Report, which gathers data from police departments around the country.

It doesn’t include crimes that most people would consider violent or potentially violent, like simple assault, domestic violence, or threatening someone with a weapon.

Domestic violence, for example, was one of the most common types of calls handled by the police, accounting for 3.4% of calls through the dispatch system. There were almost 900 reports of shots fired, which made up 3.9% of calls.

The rest of the dispatch calls are a hodgepodge of irrelevant chatter and life-threatening crises. Police are called to deal with illegal parking, suicide threats, drug overdoses, home security alarms, fistfights and fireworks. The dispatch system also includes police-initiated reports of arrests, warrants served, “park, walk and talk” community relations activities, lunch breaks and shift changes.

Some activists in favor of “defunding the police” – a nebulous slogan that encompasses anything from decreasing police funding incrementally to abolishing departments completely – have advocated “unbundling” police activities. That means armed police officers would only respond to certain crimes, while other people, including social workers, would respond to the many other types of calls police now handle.

Proponents of this approach see police continuing to respond to violent crimes. But semi-violent situations, or situations that don’t rise to the UCR definition of violent crime, complicate that idea.

Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza mentioned domestic violence in an NBC interview as the kind of issue where a social worker should respond instead of a police officer.

“What we’re saying is, invest in the resources communities need. So much of policing right now is generated and directed toward quality of life issues: homelessness, drug addiction, domestic violence and conflict,” she said.

But while some domestic violence calls may involve minor incidents, some can turn into murders, not only of domestic violence victims, but also of the people responding. One study estimated that six officers are killed on average every year while responding to domestic violence calls, and over 4,000 are assaulted.

“Domestic violence is an awfully broad category, so I think there are certainly instances where I would think you would want an individual who is well trained in tactics,” said Avidan Cover, a law professor at Case Western University who specializes in civil and human rights. While social workers could create better outcomes than police in less volatile incidents, “How you make determination, say, at the dispatch level is a very difficult [question].”

Cleveland’s dispatch system also contains codes that offer clues to what happened when police responded to those calls – in many cases, not much. (The police department hadn’t answered our request for information about the CAD system or disposition codes by press time.)

When police responded to calls labeled as domestic violence, the most common code was “ADV” – which, in the Cincinnati dispatch system, is translated as “Advised.” That accounted for 14% of domestic violence calls. The second most common was “NC,” which probably means “noise complaint.”

Only 2.4% of those calls are labeled as ending in “ARR,” or arrest.

That’s far lower, for comparison, than the percentage of Cincinnati domestic violence calls that end in arrest. For the same time period, nearly 14% of domestic violence dispatch calls there ended with an arrest. The most likely outcome label was “offense report,” which accounted for a third of cases.

Police responses to “shots fired” calls were even less likely to yield results. In a third of cases, police labeled those calls as “UTL,” or “unable to locate,” likely meaning the shooter didn’t stick around until the cops arrived. Another 7% are labeled “GOA,” or “gone on arrival.”

Less than half a percent of shots-fired calls ended in an arrest.

Cover noted that in a best-case scenario, outcomes other than arrest indicate officers successfully mediated a conflict or de-escalated a situation, or at least made the community member who called them feel heard and supported. In a worst-case scenario, it can mean officers failed to take a report seriously.

There’s no shortage, in Cleveland or nationally, of media stories about police failing to help victims. Last year, a Plain Dealer project focused on a woman who reported her violent rape to the Cleveland police. After months of waiting for an arrest, she learned the detectives initially assigned to her case hadn’t made a single phone call to find out her rapist’s identity.

As the #defundpolice argument has picked up steam, survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault have posted countless stories on social media about police failing to act when called.

One time I escaped an abusive boyfriend and I moved into a new place and then a letter showed up at my new address for him letting me know he'd found me so I called the cops being like he found me he's gonna kill me and they were like 🤷♂️ okay well let us know if you die

— Kivan (@KivanBay) June 9, 2020

When crime victims can’t count on cops to protect them, Cover said it adds a second element to the “defund the police” argument.

“One [element] is, calling the police results in violence to people: unnecessary, state-sanctioned violent death; and the other is, why even bother calling [if] the work they’re doing is ineffectual. If that’s the proposition...maybe you shouldn’t call the police,” he said.

Cover said that he doesn’t support defunding the police, and believes that effective, safe policing may require even greater police funding. But he also pointed to Cleveland’s 2019 budget, a third of which went to policing. Meanwhile, public health, economic development and housing each got two percent or less.

“Those priorities seem out of whack to me,” he added.