Wealthy Ohio State Lawmakers to Gain From Income Tax Cuts in Budget, Average Ohioan Will Save $75

Some of the wealthiest state lawmakers stand to save thousands of dollars annually on their taxes thanks to changes they enacted in the state budget.

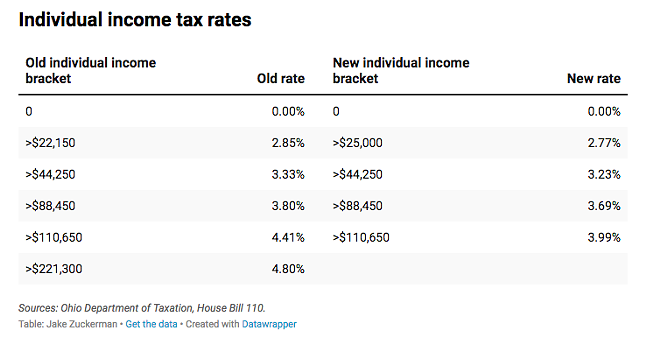

Lawmakers lowered tax rates for all income earners and raised the minimum threshold at which Ohioans pay taxes on their income.

They also eliminated the top bracket (previously $221,300 and up), which allows those earners to pay a lower rate that was previously reserved for more modest earners.

The cuts will cost $1.85 billion over the next two years, according to analysis from the Legislative Service Commission. Take Sen. Bill Reineke, a Republican from Tiffin whose family operates a chain of car dealerships. In 2020, Reineke earned at least $684,000 from 42 revenue sources, not to mention his salary as a then-member of the House of Representatives.

Factoring in his current Senate salary of about $70,000 and his reported income last year, Reineke will save about $4,900 on his taxes this year compared to last thanks to the tax cut.

Sen. Jerry Cirino, R-Kirtland, earned at least $361,000 last year between serving as a county commissioner (a post he no longer holds), drawing retirement benefits, serving on boards, and receiving at least $150,000 from a family trust.

Using his current salary and last year’s earnings, Cirino will save about $2,300 thanks to the new cuts.

The average Ohioan earns about $51,500 annually, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This yields a tax cut of about $75 under the new policy.

The Ohio Capital Journal coupled 2021 legislative salary data, set in state law, with data from 2020 financial disclosure statements lawmakers file annually with the Joint Legislative Ethics Committee. The JLEC data only provides a range of each separate stream of income, so low-end estimates are used in this report.

Some income estimates are likely lowballs — state ethics rules require disclosure of all income streams, but the top tier spans all income $100,000 and up. Some lawmakers have multiple revenue sources in this category. The income doesn’t reflect potential gains from ownership in stocks, which is not considered income for tax purposes until the shares are sold.

Economics of tax cuts

Income tax cuts make states more competitive to attract both new jobs and people to fill them, said Ulrik Boesen, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, an economic think tank. By reducing the income tax rate, the state allows taxpayers to keep more money in their pockets and increases the chances of companies investing in the state.

“What they've done is simplify by eliminating a bracket. They're given some tax relief to people who make the least by raising the bar level, and then they've cut taxes across the board,” Boesen said. “The main goal of this kind of thing is to provide relief to taxpayers, and then make sure that Ohio remains a competitive state that people want to move to, want to stay and want to have careers.”

Others, however, have criticized the rate reduction and shrinking of the income tax bracket as being relief for the wealthy, with only modest benefits for the average Ohioan.

Citing an Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy analysis, Policy Matters Ohio, another think tank, noted that the elimination of the top bracket and the lowered 3.99% income tax rate account for almost half the total $2 billion tax cut, or more than $400 million a year, going exclusively to affluent taxpayers.

“It took Ohio's already unfair tax system and made it much more unfair. It increased the inequity of our tax system,” Wendy Patton, senior project director at Policy Matters Ohio, said. “It used $2 billion in public resources that were desperately needed to ensure a great public school in every neighborhood, help rebuild our communities after the recession and provide public services that benefit all Ohioans, not just the wealthiest Ohioans.”

In a floor speech, Sen. Kristina Roegner, R-Hudson, said tax cuts are a precursor to reining in state spending.

“The only way we can cut spending is to starve the beast,” she said. “To starve the beast, we have to cut taxes. And that’s what this budget does, and we do a really good job of that in this budget.”

Rep. Brigid Kelly, D-Cincinnati, said that rather than using the budget as an opportunity to assist working class Ohioans, lawmakers have created new obstacles. She called the income tax cut “the same old song: cut taxes for the wealthy and everyone will benefit” and voted against it.

“We cannot continue to look out for the people at the top at the expense — literally — of everyone at the bottom and in the middle. If this was truly a people-focused budget, we would be making different choices,” she said. “Too many people in our state are still struggling, and even if we don’t want to help them up, we cannot continue to hold them down.”

The Ohio Capital Journal reached out to the 18 of the wealthiest lawmakers to discuss the tax cuts. Most did not respond to inquiries.

Rep. David Leland, D-Columbus, is among the wealthier members in the General Assembly and one of few who voted against the state budget. He said state coffers are flush now with federal stimulus funds, and criticized lawmakers who passed cuts for the wealthy that will outlast the one-time federal funds.

“What we’re doing is helping people that don’t need our help,” he said. “We’re helping people that have a ton of money and they’re not going to even notice the extra $5,000 or $5,400 that goes in their pocket.”

Senate Minority Leader Kenny Yuko, D-Richmond Heights, voted for the budget given its reworking of how Ohio funds public schools but noted in a statement he asked Gov. Mike DeWine to veto the income tax cuts.

He said he has “consistently opposed tax cuts that disproportionately benefit wealthy Ohioans and deprive our state of the revenue we need to invest in education, childcare and economic development.”

Ohio Senate Republican spokesman John Fortney called comparisons of the cuts’ effects between wealthy and poorer people the “class warfare agenda of the political left.” He emphasized that the budget also raises from $21,000 per year to $25,000 per year the minimum a person must earn before paying any income tax.

“Regardless of what someone earns, we believe it is their money first, not the government's money,” he said.

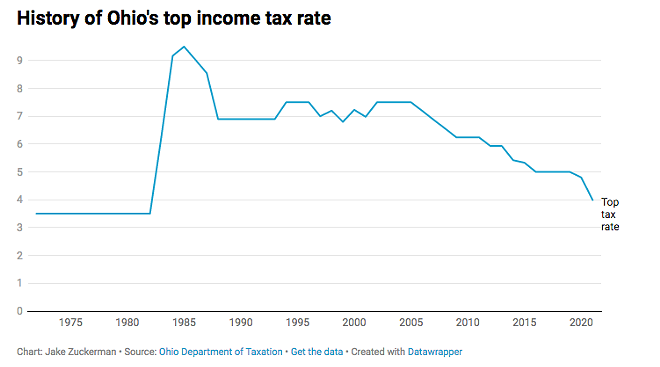

Ohio first levied an income tax in 1972, taking 3.5% of all earnings over $40,000.

The rate stayed there until hikes in 1982-1984 lifted this top bracket rate to 9.5% of all income over $100,000. From there, the rate has fallen to its new low of 3.99% of all income over $111,000.

During this time frame, lawmakers scrapped several other taxes aimed at the wealthy. In 2011, Gov. John Kasich signed a law eliminating the estate tax, which imposes a levy on estates worth more than $338,000.

In 2013, they exempted owners of limited-liability companies, “S corporations,” partnerships and other pass-through entities from income taxes on their first $250,000. This costs the state more than $1 billion annually in revenue. The Columbus Dispatch reported in 2017 that nearly half the General Assembly benefits from the deduction.

In this context, Leland said, the latest income tax cuts are the latest iteration of a failed notion of Ronald Reagan-inspired trickle down economics.

“This has been the history of this administration and this party for a long time,” he said. “There’s really nothing new here. It’s a race to the bottom.”

Originally published by the Ohio Capital Journal. Republished here with permission.