- Doug Brown, Cleveland Scene

The interior occupancy signage beneath the bathroom knobs in the Coast Guard station’s hangar-type annex say “Secure” and “Unsecure.” I’m in here, disrobing and then promptly re-robing in sweatsuit-style long johns the color of dried mud. I put on booties, size L, over my socks, and reflect idly that “Insecure” would be more appropriate for more reasons than one.

It’s now two days after my out-and-back with the Morro Bay — chronicled in this week’s cover story — and I’m alarmed to see the ice breaking tug still in port when I arrive at the station for what has been described, in press materials, as an ice-rescue demonstration. Before I commence what I anticipate will be a terrifying ordeal, I flag down Colby Bradford, a machinery technician, who’s smoking a cigarette on deck.

He says the Neah Bay (the other tug moored in Cleveland) had a part they needed for a repair but nary the expertise to install it. They’d called a contractor to come do the job and he's supposed to arrive later this afternoon, after which, Bradford says, the Morro Bay will get underway once again. Their first stop now is a Canadian freighter up North which has been frozen stuck for at least 48 hours. (As of 2/18, the Morro Bay was still in Cleveland, the repairs way more involved than everybody thought).

I salute Bradford, and feel stupid immediately for doing so, but then head back to the ice rescue stuff, where a couple of TV crews have assembled for what’s looking more and more like an event designed expressly for TV media types, you know, to get some funny b-roll. If nothing else, I figure, I’ll suit up and see what the water’s really like.

By the time I'm in my long johns, there hasn’t been any real safety instruction beyond common-sense reminders on the order of “pay attention” and “if you get water in your suit, let us know.”

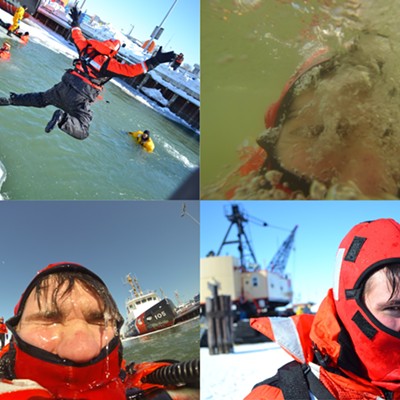

In my long johns, I eye the drysuit before me. It is elaborate. As Petty Officer Walter "Sean" Vitou guides my extremities into the appointed holes, I cannot shake the image of myself as knight, Vitou as squire, pre-joust. Literally enmeshed in this suit are zippers and harnesses and an involved network of interior pocketry. There are attached “ice picks” which don’t initially impress in terms of heavy-dutyness, but do seem like they might be useful in a pinch.

Vitou, with fair warning, zips up a horizontal zipper over my crotch.

“It’s the pee zipper,” he says. “You wanna make sure that this is pulled tight and that there’s no gap. That’s ice cold water and at first it feels like needles, and it’s got pin point accuracy. And it’s like ‘oh man’ I can feel it. Once that numbness goes away it just starts filling in and you’re like ‘forget it.”

Forget it? Like — excuse me — forget my penis? Vitou says water might leak in at my wrists and at my neck, but otherwise I should be fine. The suit is designed in quadrants so that leaks don’t spread. I secure and then re-secure the pee zipper. All told, putting on the suit takes about 15 minutes, with Vitou’s help. In emergency situations, Vitou says, Coast Guard rescuers can be fully suited in a matter of seconds. I cannot overstate how impressive this is.

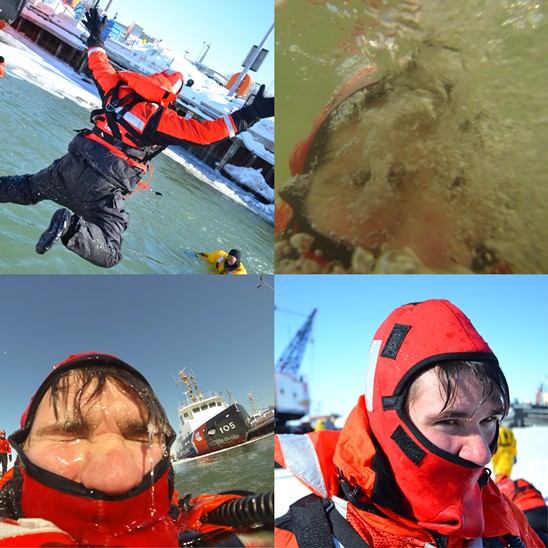

I had been told I’d be “playing victim,” for the day’s demonstration, but once I arrive down at the ice, waddling to the oblong and formidable water hole and feeling out of place, there’s no organized rescue simulation going on at all. The people at the water’s edge — and it’s impossible to tell who’s in charge — basically tell me to jump in at will. I’m told to crawl out military style, rolling away from the hole, keeping my elbows close to my chest but otherwise am encouraged to just have at it. A few firefighters suggest that I actually jump in, do a cannonball or something, this presumably for their amusement.

In this regard, I am likened to the prototypical ice-rescue victim, at least in Cleveland, to whom Vitou ascribes a lack of common sense.

“Sometimes it’s just natural curiosity,” Vitou says. “People want to go take pictures of the ice or actually get courageous and go walking on it.”

The whole point of today, other than ancillary PR stuff, is safety training for nearby fire departments. Their response times are so much quicker, and even though the Coast Guard always responds to calls, it's prudent to have local rescue crews know the procedures and protocol out on the ice. Vitou reports happily that they’ve had no ice rescues this year.

“Go ahead. Jump,” says someone, and I realize I’m just swinging my arms near the water, consciously or unconsciously stalling. The pool before me looks relatively calm, and a handful of trainees are in it already, so I trust it can’t be that bad.

What the hell, right?

My run and midair flight are horribly non-distended. What I mean is, it’s not like the moments before hitting the water are perceived in slo-mo because what’s coming is so shocking or scary (a sensation I sort of expected).

Just the opposite. It all comes rushing at bewildering speed directly toward my face. And despite the buoyancy of the suit, I’m submerged for a few moments and the water floods my hands and wrists and face and neck, as Vitou predicted. The rest of my body remains dry.

But my face. The water slinks through the cracks in my mask and I cannot, strictly speaking, breathe. I’m experiencing what I’m fairly certain is suffocation but try to remain composed for appearances’ sake. I sense that the firefighters and watercraft folks may be watching and giggling at me in their peripheries.

My bangs, such as they are, are freezing to my forehead, and it’s a process I can feel in exquisite detail. What strikes me now, about ice, as my hands are becoming blocks of same (=ice) and the freezing water hardens on my exterior harness, is not its otherworldliness. It’s not the shapes or colors or seismic configurations it assumes out on the Lake. It’s certainly not its omnipresence. (Once again, this is all chronicled with lots of vivid metaphors in this week's cover story).

No, as I’m bobbing in this water hole and dog-paddling to the edge while the TV crews may or may not be filming, and considering seriously that I'd like re-enact Jack’s tragic final scene from Titanic, the only magician’s poof of a thought I can mentally summon about ice is that it’s really, really cold.