Casandra Vasu says that she's been spit on, called a bitch and the c-word, and nearly flattened by cars. She's had plastic bottles and water thrown in her face. All for simply daring to ride her bike in the street.

Vasu, who commutes by bicycle from her home in Detroit Shoreway to her job at St. Theodosius Church in Tremont five days a week, says that some days she's afraid to get on her bike at all.But she does anyway. She and her husband only own one car — she gave up hers to save money when she was unemployed a few years ago —and she likes the exercise and feeling of accomplishment she gets from riding her bike.

"I really enjoy cycling," says the 37-year-old. "I've never been an athletic person and I still sort of revel in the fact that I'm able to get around the city with my own two legs, that I can get from Point A to Point B by the strength of my own body. It's really something that I take pride in.

"There are a lot of people I know who won't really ride much anymore because of aggressive motorists," she adds. "For me, honestly, no matter how many bad days I have with drivers, I don't really think I should let them win."

If you set aside the bit of self-appointed martyrdom, Vasu has a pretty good point. Why should she feel as though she's risking her life every time she gets on a bike? Especially and ironically since a portion of Vasu's route has dedicated bike lanes. Yet those haven't stopped drivers from buzzing past her just inches from her handlebars or turning into her with a "right hook."

After spending years in the slow lane, Cleveland is finally stepping up its efforts to become more bike-friendly. We're on track to add 70 miles to our bikeway network by 2017 (compared to 2013), an increase of nearly 150 percent. Bike commuting is also up from .6 percent to .7 percent in the past few years, and it's risen nearly 240 percent in the past 15 years. Cleveland is currently ranked seventh among the top 50 largest cities where bike commuting is growing the fastest (behind Detroit, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh).

Yet Cleveland cyclists — who have to not only battle long winters, crater-sized potholes and clueless drivers — say there's a long way to go before they feel safe on the road.

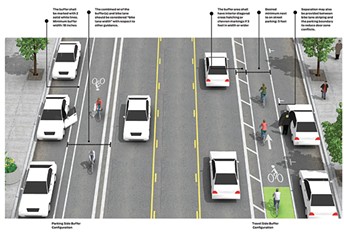

"Cleveland's cycling infrastructure is not great – there's lots of peril out there for cyclists trying to get around," opined cyclist Jarrod Zickefoose on Facebook. "Protected bike lanes that allow cyclists to do functional cycling, like commuting, as opposed to recreational cycling would be ideal. Buffered lanes would be an improvement on the current situation. Non-buffered bike lanes and sharrows [shared lane markings] are kind of pointless."

Although it's too early to tell the impact of Cleveland's new bike infrastructure, according to data from the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), conflicts between bikes and cars are going up, not down. The number of bike crashes in Northeast Ohio rose by 10 percent from 2008 to 2011, according to the agency's 2013 regional bike plan summary. "This increase is alarming because total crashes for all vehicles region-wide decreased 4 percent from 2008 to 2011," the report notes.

Advocacy group Bike Cleveland says the city deserves a B- grade overall because its approach to bike infrastructure has mostly been to restripe existing roadways rather than create dedicated facilities for cyclists. Having more separated and protected bike lanes could improve safety, cyclists say, yet the vast majority of Cleveland's bikeways are either sharrows (painted roadway signs) or bike lanes with no buffer from traffic. That places us at risk of falling further behind cities like Pittsburgh, they say, which installed a protected bike lane on Penn Avenue a year ago and saw a surge in ridership.

"We have all these policies and plans that say we want to be a bicycle and pedestrian friendly city, but when it comes to engineering it, that's where we're falling short," says Jacob Van Sickle, executive director of Bike Cleveland. "We have a Complete and Green Streets ordinance, and I think the city should just say, 'We're going to implement it.'"

The West 25th bike lane debacle

Recently, a controversy between the cycling community and Cleveland's traffic engineering department around the new West 25th bike lanes blew up, placing the city's bike infrastructure in the national spotlight when it became a viral Internet meme.

You see, in September the city striped out bike lanes on 25th, and traffic engineering, in its infinite bureaucratic wisdom, put the buffer on the right side (between the cyclist and the curb) rather than the left side (between bikes and traffic). City officials claim this right buffer design is safer because it makes cyclists more visible to cars and reduces right hook accidents.

Oh yeah, and they also forgot to tell anyone. The first time cyclists learned of the striping plan was when they saw it on the street.

Bike Cleveland leaders were furious. "Buffers are great because they create space between vulnerable people and cars; they protect people and we love them," Van Sickle told Scene. "You know what doesn't need protection? A concrete curb."

A Streetsblog story by Cleveland writer and activist Angie Schmitt, titled "Cleveland traffic engineer puts buffer on the wrong side of the bike lane," quickly went viral, generating nearly 200 comments online. A picture of a man riding in the right side buffer on 25th — exactly what the city's traffic engineers says that he's not supposed to do — was widely shared on Twitter.

In an email to members, Bike Cleveland called out the city's traffic engineer, Andy Cross. "We think that it's wrong the City simply dismisses the National Association of City Transportation Officials guide to bike lanes despite it being fully endorsed by the Federal Highway Administration."

The city denied an interview request with Cross, but Bike Cleveland shared an email that he sent regarding their complaints about West 25th. "The terms 'best practices' and 'protected' are often used with what is shown in the NACTO guide," Cross wrote. "A design that encourages or requires hook turns across the path of through cyclists is neither a 'best practice' nor 'protected.'"

Cleveland's sustainability chief, Jenita McGowan, vigorously defends the new bike lanes. "We put in buffered bike lanes when we think it's safe to do so," she says. "We understand that cyclists feel safer with a buffer between the car and their bikes. The reason we did not put in a left-side buffer on 25th is that there are numerous intersections right in a row leading up to a very complex intersection. We're not willing to create facilities that create the perception of safety versus the reality of safety."

Several local officials, including Ohio City Inc. director Tom McNair, councilman Joe Cimperman and NOACA representatives, declined comment for this story. Yet privately, several area transportation experts agreed that the West 25th bike lanes are backwards. Pictures of the design on the Internet left many national transportation planners shaking their heads.

"The simple definition of a buffered bike lane is not met by what was just implemented in Cleveland," says Matt Roe, director of the Designing Cities Initiative with NACTO in New York City. "It's very common and accepted to drop the buffer on the intersection approach. You're telling bikers that cars might be turning across, and telling cars to move over to the right if necessary.

"It's bizarre," Roe adds of the West 25th bike lane design. "As shown in the photo, it's bizarre."

McGowan said in a followup email that the city's policy is to put in right side buffers where the curb cuts are less than 300 feet apart — in other words, on nearly every single street in the city of Cleveland.

Van Sickle cites studies like the one completed by the University of British Columbia in 2012 showing that a cyclist is 10 times more likely to be injured on a busy street with parked cars than on a cycle lane alongside the street, separated by a physical barrier. The city could have developed a separated or protected bike lane on 25th, but chose not to, he says.

Studies have shown that separated facilities grow ridership up to 300 percent. "We've tried vehicular cycling for the last 50 years in the U.S.," says Van Sickle. "It hasn't worked. It won't get people from 8 to 80 to ride their bikes."

A precedent for bad design?

Unfortunately, Cross is far from done wreaking havoc on the city's bike infrastructure. Van Sickle and other advocates have seen preliminary designs for Lorain between West 129th and West 150th, which they say include the same flipped buffer design. Lakeshore Boulevard, which is now in the planning stages, also has buffers on the right side. West 25th could set a dangerous precedent, they say, making it harder to obtain separated or protected bike lanes on other city streets.

"We do think it's wrong that a mid-level traffic engineer with the City of Cleveland can basically unilaterally design bikeway infrastructure in our city without any input from anyone else," says Bike Cleveland marketing and membership director Rob Thompson. "If their bosses won't raise questions, then we're going to ask them."

Perhaps the greatest irony of the West 25th bike lanes is that Andy Cross is actually an avid cyclist. "Andy Cross is a lifelong and frequent cyclist and it gives him a full perspective on the hazards that bicyclists face," McGowan wrote in an email. "He knows what it is like to be on a bike in traffic. So, he is not just designing out of a book, but also out of experience."

Yet while Cross may be comfortable riding with traffic, many cyclists aren't. A graph from the Portland Bureau of Transportation shows that only eight percent of the city's cyclists define themselves as "strong and fearless" or "enthused and confident," while 60 percent are "interested but concerned." Cleveland could do a better job accommodating these cyclists, Van Sickle says.

While cyclists who disobey traffic laws are part of the problem, separated bike infrastructure helps reduce conflicts. For cyclists, the backward bike lanes on 25th are just one example of where the city has made it hard for cyclists. They complain about the inbound lanes of the Detroit Superior Bridge, where cars often speed up to 50 miles per hour and cyclists are funneled out of a confusing bike lane into a busy intersection. Van Sickle is also still frustrated by the city's inexplicable elimination of bike lanes along Ontario south of Public Square.

"There are certainly some missed opportunities," he says.

Cleveland passed a Complete and Green Streets ordinance in 2011 that "requires implementation of sustainable policies and guidelines in all construction projects within the public right of way," according to the Sustainable Cleveland 2019 website. Yet Van Sickle says that many city streets have been redone in the past four years with only minor tweaks, if any at all, to bike infrastructure.

He says that for Cleveland to become more bike-friendly, we have to be willing to slow down traffic. For example, bike lanes are likely being eliminated from Prospect where it's being repaved west of Bolivar. Adding bike lanes would require the removal of 100 on-street parking spaces, but apparently no one wants to piss off the businesses. The city is missing a chance to create a great connector, Van Sickle says. "There's so much parking on Prospect already," he says.

Part of the problem is that the city's traffic engineering department is woefully understaffed. Other cities — including Detroit — have whole teams of people working on bike lanes. "The city needs to hire someone [else] that solely focuses on engineering bike lanes," Van Sickle says.

'We could be awesome tomorrow'

Despite the controversy over West 25th, the city is doing a great job striping bike lanes, Bike Cleveland says. The bike lanes on Detroit have been a game changer. Many streets beyond the gentrifying near-westside have also gotten bike lanes, including Denison, Bellaire and Puritas — in some cases, over the objections of residents and councilpersons.

This fall and into next year, even more bike lanes and sharrows are being added to city streets. These streets include West 14th, Prospect, Community College, East Boulevard, Harvard, West Boulevard and West Third, among others. The city is even building the first contra-flow (against traffic) bike lane on East 22nd Street in the Campus District, which will include bike-only signals.

Cleveland also recently moved ahead with its first separated bike facility. "A two-way separated bike lane has come forward in the final recommendations of the Living Lorain Plan, described as a complete street," reported GreenCityBlueLake in a recent story. Various options are being considered, including reducing Lorain from four lanes to two, but all have a cycle track.

GCBL's Marc Lefkowitz said city officials must have had a lightbulb moment when they visited Indianapolis, a Midwestern city that has surged past Cleveland by aggressively adding new bike infrastructure, and saw the Indy Cultural Trail.

"They were impressed by the sanguinity of the mayor who says he fields calls from businesses insisting on space on the Trail," Lefkowitz wrote.

As this story went to press, the Cleveland Planning Commission unanimously approved the new protected bike lanes on Lorain.

Yet the city is moving so quickly on repaving other roads with funding from NOACA's Provisional Transportation Asset Management Program (PTAMP) that detractors say it hasn't taken the time to engage the public or consider how it can best add bike infrastructure.

Streetsblog writer Angie Schmitt says Cleveland could be on par with cities like Minneapolis if it built the kind of bike infrastructure cyclists want: "Places with a high number of cyclists are willing to separate biking from cars. We could be awesome tomorrow. We have so much infrastructure, but we don't have very much money. Striping is so cheap."

Yet Schmitt's cycling utopia will have a hard time becoming a reality if folks like Councilman Mike Polensek have their way. "There's this big rush to put bike lanes everywhere," he complains. "Some of them are not thought out very well. Whatever's done on Lakeshore, we have to make sure it accommodates vehicles. There's more cars than bikes, that's a given."

Van Sickle hopes to change the opinions of Polensek and other skeptical officials. He's working with city planning on a Transportation for Livable Communities study of the Midway project. The idea is to develop guidelines and recommendations around protected bike lanes, and then construct them on extra-wide streets like St. Clair Avenue. He's also working with the city and NOACA to study turning the southern lane of the Detroit Superior Bridge into a bike lane.

The group continues to try to build a larger constituency for cycling in Cleveland. There's a lot of positive energy around biking right now, Van Sickle says, with monthly Critical Mass rides attracting upwards of 500 people during the summer.

"Bike infrastructure is not just good for cyclists, it's good for pedestrians and neighborhoods," he says. "It's good for the whole city."