Trump's Word Dump: Pricey Talk and Cheap Feelings at the #RNCinCLE

In the rush to declare “winners and losers” of the Republican National Convention, the city of Cleveland came out overwhelmingly on top in the headlines. “We were promised a riot, we got a block party instead,” wrote the Washington Post, while the L.A. Times documented the post-RNC “victory lap” taken by Cleveland’s business and political leaders. “Mistake on the Lake no more,” Cleveland.com grandly proclaimed. And the New York Times hailed the “loud exercise” of First Amendment rights on the newly renovated Public Square, causing The City Club of Cleveland to swoon on its Facebook page: “We [heart] free speech.”

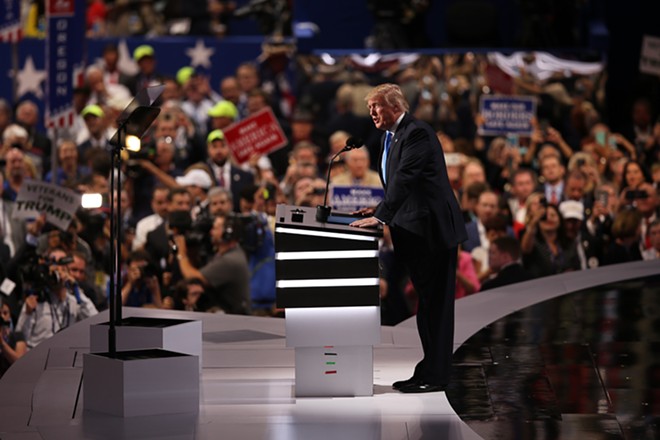

If it weren’t for questions about a five-million-dollar fundraising shortfall in covering convention-related costs, and the loss of regular business by establishments located outside the eye of the RNC hurricane, it would be impossible to say that hosting the convention was a bad thing for the city in and of itself. The Trump campaign’s orgy of demagoguery had to be broadcast from somewhere, and was otherwise mostly contained by the walls of Quicken Loans Arena. Downtown Cleveland looked as good as ever and the streets had an undeniably positive feel, even despite the at-first-jarring presence of massive security fences and armies of police imported from all around the nation. (“[The RNC] is like ‘It’s a Small World’ for cops,” noted one visiting journalist.) All else equal, it’s nice to leave your troubles behind, get dressed up, and have folks pay some attention to you every once in awhile. In this sense, Cleveland was properly dressed to the nines and painted the national consciousness red.

But what about the other 98 years per century when a major political party won’t host its national convention here? And what’s so good about free speech on Public Square when it has little to no chance of influencing the public policy set by those inside the arena? Here, the layers of security that radiated from the convention floor, effectively isolating protesters from the convention’s participants, served as an apt metaphor for the resounding success of the Republican Party’s sustained effort to replace the vote with the dollar as the fundamental unit of American democracy. With limits on campaign spending having been obliterated by the Republican project, the barriers between citizens and politicians, politicians and accountability, have never been so impenetrable.

And now that only the most expensive speech is “heard” in any politically meaningful sense, words mean less than ever in the political context. As the cost of political speech skyrockets, its availability and diversity naturally plummets, and a billionaire demagogue can be increasingly sure that the few with the means to counter his emotional appeals with logic will be increasingly less inclined or less able to do so effectively. Which explains as well as anything Trump’s rise to the Republican nomination, culminating in his display in Cleveland last week.

“The crime and violence that afflicts our nation today will soon come to an end.” “Nobody knows the system better than me, which is why I alone can fix it.” “We are going to build a great border wall to stop illegal immigration.” “I’m going to bring our jobs back to Ohio and to America – and I am not going to let companies move to other countries without consequences.” “We are going to Make America Great Again.”

The implausibility of Trump’s claims mattered much less than the context in which they were proclaimed and the feelings they aroused as a result. As Nathan J. Robinson recently pointed out at Current Affairs, “global inequality has risen to the point that nearly all wealth is controlled by a tiny minority of the super-rich, and labor power is in decline.” Yet, the Democratic Party—as beholden as ever to this “tiny minority”—has been largely confined in responding to Trump with an argument that “America is already great.” In the absence of “a compelling alternative vision and program,” says Robinson, “of course people will be susceptible to demagoguery about crime and immigration.” While “Trump ... may have a racist and delusional explanation for the cause of the world’s troubles, [at least he has] an explanation.” And in today’s profoundly warped market for political speech, any old explanation might do.

In Donald Trump’s America, you can [heart] free speech all you want, but the speech that really counts is anything but free. And in the absence of meaningful speech, feelings will naturally take over. Regardless of whether Hillary Clinton can figure out how to stir enough emotion to beat him in November, if the barriers to meaningful political participation remain as constructed there will be plenty worse to worry about than a President Trump.