The SUV coasts through the dead center of Ohio Amish country. Under a blank June sky, the Holmes County landscape is a picture postcard of country charm: A tight two-lane road lassos around green hills, the acres dotted with barns and the farmland studded with the five o'clock shadow of early crops. Amish men and women pass by on foot or in horsedrawn buggies, each of them waving to the familiar car as it navigates the rolling road.

The woman behind the wheel pulls over alongside a windowless single-story structure, no bigger than a suburban bungalow. The building's sides are shedding white paint, and a small open vent about half a foot wide runs the length of it. Nearby, cows graze as a young Amish woman goes at a hedge with a weed whacker.

"They're in there," the woman behind the wheel says, pointing to the building. "Hundreds of them."

She rolls down the car windows. Outside, there is only the mechanical whine of the weed whacker and sporadic moos from the lounging cows. Suddenly, the driver tears through the calm with a long blast of her car horn.

The building explodes with barking in reply. Hundreds of tiny voices yelp and croak from inside, a canine pandemonium that rocks the air for a full minute before falling off to an eerie post-storm silence.

"Dogs," the driver says, pulling the car back onto the road. "A lot of dogs."

All through the uproar, the Amish woman never even turns around. By now she's likely accustomed to the outside interest.

The driver, who asked not to be named, is one of about a half-dozen non-Amish who haunt these country roads looking for such buildings. When they find one, they'll try to peer through windows or doors. If it's windowless or shuttered, they slam on the horn, expecting to hear an outburst. The point isn't to cause a scene or to scare the animals, they say, but to make sure the dogs are still there.

These outsiders are a loose band of animal advocates and dog rescuers; the buildings they're prowling for are dog kennels — or what critics term "puppy mills," part of a backyard breeding business that's taken hold in many of the rural counties south of Cleveland.

In particular, assiduous Amish in communities around Holmes, Tuscarawas, and Coshocton counties have embraced the puppy trade. The region has become a highly profitable hotbed for a loosely regulated, untaxed cash business that rakes in millions of dollars each year.

The three counties combined boast 1,200 kennel licenses; Holmes — considered the capital of the trade — has 400 licensed breeders among a total population of around 40,000 people. In comparison, Cuyahoga County has around two dozen licensed breeders.

Although exact figures are hard to drum up, Holmes officials estimate that at any given time there are around 8,000 canines in the county. The breeding trade has been so successful here that locals have become industry innovators; in 2004 a group of Amish businessmen opened the Buckeye Dog Auction, a venue for breeders from all around the country to sell their dogs in a manner similar to a livestock sale.

But while staking a claim in the business, Amish breeders have also drawn fire from animal-rights groups over kennel conditions and the quality of their product. It has set off a long and loud back-and-forth between breeders and activists, and the fight's been far from clean. Confrontations, protests, inflammatory propaganda, boycotts, and even lawsuits — each side has unloaded an arsenal at the other. But at the heart of the issue is a cultural continental drift between two groups that see dogs in completely different lights.

Every time a member of young Hollywood prances before a barrage of flashbulbs with a fear-frozen chow tucked in her purse, rural puppy mills pump out another batch.

Demand for the cute and cuddly has always been high, but an increased interest in toy breeds took root a decade ago thanks to celebutantes looking to accessorize with a Poodle or Pekingese. The fad was a good fit for backyard breeders: A large number of small dogs can be kept in less space, meaning a small-time operation could compete for a slice of the growing toy dog trade.

Around the time teens began emulating Paris and Nicole en masse, the Amish communities surrounding Holmes were in need of new cash flow, according to Ervin Raber. The man many consider the don of the area's Amish dog breeders, Raber is equally respected and reviled for his business chops. He was one of the first Amish to jump on the trend, setting up a high-volume breeding business and co-founding the Buckeye Dog Auction. He's also probably the only Amish in Ohio with a considerable Google footprint: Unlike other Amish, who dodge outside attention, Raber has become a vocal defender of what he sees as an integral part of his community's life. As a result, he's often quoted in news reports on the subject and targeted on activist websites. To them, he represents the heart of the problem.

Despite what you might expect, the Amish were not immune to the recession. Many Holmes County Amish make their living with manufacturing jobs in nearby furniture and lumber plants. But as demand slowed to a trickle in the early 2000s and hours were slashed, Raber says, some steered toward breeding as a way to put food on the table.

"It's a real nice supplemental income," he explains. "When times were tough, it helped tremendously to keep everybody afloat."

Not all area Amish signed on. The population is divided into separate communities ruled by bishops who decide what the rest of the flock can and cannot do. But in areas where breeding is allowed, the practice quickly flourished. Breeders found they could sell dogs for at minimum a couple hundred dollars each, meaning high profit for low overhead. By the mid-2000s, kennels were king in Holmes County.

Today, Amish country kennels are ubiquitous, and their sizes vary. Some larger kennels are barn-like structures, with only a few openings for air and light. Many others resemble chicken coops, with wire cages connected along the side. They also range in quality: Some are freshly painted and sturdy; others seem a strong wind away from toppling over.

According to activists, conditions in many Amish facilities are poor. Advocates say they've witnessed animals exposed to constant isolation, extreme weather, feces, and cramped living spaces.

"The conditions in Holmes, Tuscarawas, and Coshocton are terrible," says Martha Leary, a dog rescuer with extensive experience inside the mills. "They live in tiny wire-bottom cages, normally 18 by 18 inches. Most of them have automatic feeders and water dispensers, which is the same that a hamster would have. It's not the conditions for a companion animal."

Many say the worst victims of the puppy mills are the breeding animals who spend the majority of their lives in these kennels. While puppies are eventually sold, their mothers and fathers are confined in pens and bred again and again, until they are physically exhausted.

There is hope for some of them. Once they've been bred to the max, some fall into the hands of rescuers like Leary, volunteers who develop sensitive yet trying working relationships with the breeders. When a dog is finished, rescuers get the call. For them, the exchange is a classic catch-22: If they report the conditions they see or berate the Amish directly, they'll likely lose their access to the kennels. With no one to take the dogs, they believe, many would be killed.

"These dogs are in very horrific conditions when we get them, and not just physically but emotionally," explains Kristina Lange, a dog rescuer with Mentor-based Marilyn's Voice. She took up the cause after adopting a mill dog named Marilyn; the animal died as a result of her extensive medical complications, but today Lange and her group help rehabilitate rescued mill dogs.

Breeding dogs coming out of mills face numerous ailments, she says. In many cases they've never been groomed; their teeth can be decayed, and eyes and ears infected. Some have worms or other pests; others have splayed paws.

Lange recently retrieved a Shih Tzu from an Amish breeder. When volunteers picked it up, its eye was severely swollen and jutting out like a crimson golf ball. The breeder said he didn't know what was wrong and that the eye had only swelled up that day. Later, a vet determined it was chronic glaucoma and that the dog had been living with the painful condition for years. The eye had to be removed.

The physical challenges are often nothing compared to the mental issues rescuers encounter. Mill dogs have never been treated as pets but livestock, Lange says.

"Dogs are social animals. They need and crave human interaction, and these dogs are feral; they've never been handled by human hands except to be thrown into one cage to breed." As a result, they exhibit none of the behaviors usually associated with man's best friend. They hate to be touched, have no idea how to play with other dogs, can't walk up stairs, and don't know how to drink from a bowl. It can take up to a year to socialize a former mill dog.

Perhaps even worse than the allegations of abuse are reports of the lengths some breeders will go to get rid of animals that no longer produce. According to Kellie DiFrischia, a Columbus-based dog rescuer, she and other activists have heard reports of animals being killed.

"That is something that is sadly taking place today," she says. "If breeders have a dog that's very sick or they have a litter that is born with issues, and the breeder isn't willing to put money into it, they will kill them. Can you prove it? Not really, because this is some guy in his barn drowning puppies."

Despite the gulag-like conditions of some kennels, there is little legal standing for regulators. Under Ohio code, as long as a licensed kennel provides food, water, and shelter, the operation is not in violation. Breeders who sell commercially are required to be licensed by the United States Department of Agriculture, but the agency has only two inspectors for the entire state. Even when breeders are found in violation, the punishment is little more than a sharply worded suggestion on how to improve. But the majority of breeders don't even bother with the USDA: There are an estimated 11,000 kennel licenses in Ohio, but only 200 USDA licenses — and that number includes breeders of animals other than dogs.

Reagan Tetreault, the dog warden for Holmes County, gets frequent calls to investigate Amish facilities. She follows up on every complaint, but can't do much unless there is direct proof of abuse.

"Unless there is explicit cruelty or neglect involving medical conditions, my authority is limited," she says. Part of her frustration stems from the perception she's not doing all she could. She often comes under fire from outsiders who want her to pressure breeders into better practices.

"There's a very large misconception that I don't care," she says. "That's frustrating. I'd love to be able to do more and take care of some of these things, but until it changes at the state level, I can't." (Since talking with Scene, Tetreault has left her position as Holmes County dog warden.)

The Buckeye Dog Auction is held in a livestock barn off Route 557 in Baltic, an Amish hamlet in eastern Holmes County. Early one Saturday morning in May, the dirt parking lot is already jammed with cars and buggies well before the 10 a.m. kickoff.

As a sky the color of wet pavement starts yielding rain, Amish teens sell fresh produce from a stand near the barn while a pair of bulky sheriff's deputies march the perimeter, eyeing incoming vehicles. Indoors, the turnout is nearly 80 percent Amish. Walls throughout the building are plastered with signs prohibiting cell phones and cameras, though most in attendance wouldn't own them anyway. Before the start, potential buyers are free to examine the products in adjacent semi trailers. Caged puppies are stacked floor to ceiling throughout the humid tunnels, literal wailing walls of barking animals.

The auction takes place in a large room with a raised gallery that descends to the floor. There, the animals are displayed one at a time or in small groups. It all has the feel of a high school sporting event: Amish men and women socialize in groups; a concession stand peddles popcorn and cans of soda. In the seats, boys and men closely follow the sales, marking each final price in their program as if scoring a baseball game. When it's a new dog's turn, each one is given a quick once-over by an onsite vet; a young boy then holds the twitching puppy on a table while the auctioneer calls the action in his buzz-saw carnival bark.

In many ways, the auction is the heartbeat of the entire backyard breeding world. Ohio is the only state east of the Mississippi River that allows dogs to be sold at auction, so the events draw breeders and buyers from across the Midwest and Eastern seaboard. At the May gathering, local puppies were sold alongside packs from North Carolina, Kentucky, Georgia, and West Virginia.

Conceptually, the idea of a livestock-style auction for dogs is a logical extension of the breeding business. Breeders sell the majority of their animals to brokers, middlemen who buy in bulk and then sell off the pups to individual buyers or pet stores. The auction centralizes the transaction, allowing for smoother business. The atmosphere of onsite competitive bidding also keeps the sale prices high: At the May auction, most puppies went for around $350, although intense bidding for some choice breeds, such as Yorkshire Terriers or Maltese, drove up a few tickets to more than $600.

Besides taking issue with the kennels, advocates question the quality of the dogs on sale. According to Mary O'Connor-Shaver, the woman behind a movement to ban the auctions with a ballot initiative, dogs raised in mills and sold at the auction are not raised to breed standards.

"What we have found is that many of these dogs are unhealthy, and they're not screened for genetic diseases," she says. "Sometimes they don't even look like the breed."

Others accuse the auction of hosting animals with bigger problems than weak genes. Last October, Pennsylvania-based dog advocate Bill Smith and members of his group, Main Line Animal Rescue, traveled to Holmes County for an auction. The team was on the trail of Pennsylvania breeders who were selling animals in Ohio after their home state passed a round of reforms that put a leash on improper practices. They purchased 12 dogs. Once they were home, a vet examined each one and found some with serious medical problems, including infections. The local SPCA built a case, and eventually six breeders were charged with animal cruelty. Lancaster County District Attorney Craig Stedman, who Smith says has a poor track record of prosecuting crimes related to animals, later dropped the charges. Now the breeders are suing Smith and his group for defamation; local animal activists have launched a campaign to raised awareness about Stedman's attitude toward animal crimes.

For Northeast Ohio, the biggest problem presented by the auction and puppy mills is one of quantity, not quality. Thanks to the region's proximity to the business, the Cleveland area sees a large quantity of mill dogs. According to animal officials, the market is far too flush already with needy pups, and the additional surplus puts a stress on the system.

"We have dogs still being euthanized in shelters because there's too many of them, and there's not enough space in the shelters and not enough homes," says Sharon Harvey, executive director of the Cleveland Animal Protective League. As one toy or mixed breed becomes the sudden rage and breeders accommodate with a surge of pups, more dogs end up ownerless.

"Somebody could walk into a shelter any day of the week and find a mixed breed," she says. "We have plenty of dogs to go around that have already been born."

On June 1, Senate Bill 95 was voted out of the Senate's State and Local Government committee by a vote of 7-1. For months, the bipartisan panel had heard testimony about the kennel legislation from breeders and advocates. Opponents had hoped to make the hearings a Waterloo for the bill, but ultimately were successful only in lopping off a major component of it.

The original legislation contained a provision that would have banned dog auctions; due to tag-team pressure from the American Sportsman Alliance and the National Rifle Association, the ban was excluded from the final language. Nonetheless, many expect the bill to become law when the legislature reconvenes after the summer recess.

Under the proposed legislation, the state would establish a Kennel Control Authority to impose stricter regulations on the treatment of the animals and their conditions for all breeders in high-volume situations, including guidelines on cages and mandatory exercise time. The authority will be funded by the current fee structure for licensing, according to supporters.

"Unfortunately, Ohio is known as one of the worst states in terms of puppy mills," says state Senator Jim Hughes, the bill's sponsor. "With this, the good breeders are not going to feel anything. The bad breeders, we're going to say you've either got to clean your act up or we don't want you in Ohio."

But according to Ervin Raber, the layers of new regulation would only smother the industry, Amish and otherwise. "If the bill was to pass, we wouldn't last six months and then we'd have no breeders in Ohio," he says.

Raber stands by the current USDA regulations that he says Holmes County breeders follow. Dog rescuers, he adds, are asking for the impossible. He admits there are some instances of noncompliance, but explains that the Amish community is quick to educate and correct breeders who fail to match up. Breeding is meant as a business, he says, and if Holmes County kennels were as systemically squalid as animal groups say, commerce would suffer.

"The way the American public is right now, you cannot sell an inferior product to them," he says. "These animals have to be healthy, they have to be vaccinated, they have to be fit. If they were what they tell you we are, we'd be out of business."

Raber and other breeders say reports of abuse are embellished and circulated by individuals driven more by political agendas than actual concern for animals. They characterize many advocates as city- and suburb-dwellers on the offensive against a way of life they don't understand.

And while the rhetoric heats up as a final vote on the bill draws near, some animal rescuers echo Raber, worried that finger-pointing and politics have distracted from the real issue: saving dogs.

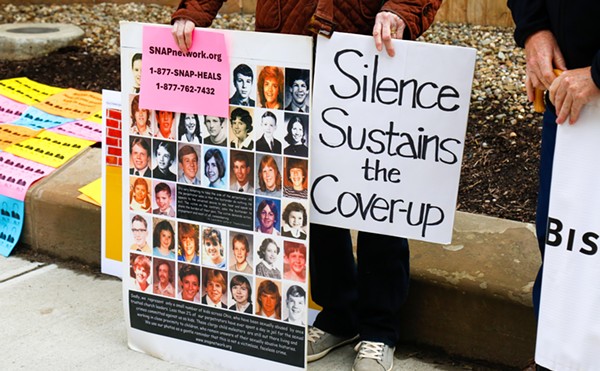

One group has taken a more visible role and drawn fire for some of its tactics. Since the auction ban was left out of the current bill, Mary O'Connor-Shaver and her Coalition to Ban Ohio Dog Auctions have organized a petition drive to collect a minimum of 120,700 signatures by the end of 2010.

At the auction in May, O'Connor-Shaver's group staged a protest outside the Holmes County Fairgrounds, 12 miles away in Millersburg. Throughout the morning, dozens of volunteers lined a major thoroughfare, hoisting signs demanding an end to Amish puppy mills and auctions. The group has also called for a boycott of businesses in Holmes County until the commissioners move to end the auctions; a similar but unaffiliated ban has been taken up by many in the rescue community who refuse to buy Amish products.

But some believe such energy could go to better uses. Donna Norfolk, president of the Holmes County Humane Society, says outsiders looking to further the cause could help more by participating in rescue than by organizing protests.

"Help me find [bad breeders], help me educate them, help me let them learn this is like any other business, and that in order to turn a good profit, you have to take care of your product," she says.

To O'Connor-Shaver, the time for negotiations has ended. She says rescuers and advocates have long tried to work with Amish breeders, but that they are intractable on the issues because they view animals as a commodity. "They have a competing philosophy, and we say that's not a philosophy we adopt, and it's not one embraced by the majority of Ohioans."

At an Amish breeding farm in Coshocton, a line of cages is shaking. Six enclosures, obscured by the late-afternoon shadow of a nearby barn, have been rigged up one atop the other and mounted into a wobbling wooden housing. Inside each cage, a puppy bounces up and down, pawing at the wire. They all bark as a group of Amish breeders and rescuers arrange an animal pickup.

Senate Bill 95 would nix kennel arrangements such as these. Wire cages would need to be coated in plastic; the openings cannot be large enough to allow paws to get caught, and half of each cage must be a solid surface, allowing the animals a comfortable place to lie down.

The activists who wrote the legislation say the new regulations are merely a compromise with breeders. The point, they insist, is not to put all breeders out of business — only those who raise animals improperly.

The safe money seems to be on the new regulations. In early July, Governor Ted Strickland brought together members of Ohio's agricultural leadership and the state's humane society, two groups previously at each other's throats over regulation. Both sides gave a stamp of approval to a litany of changes to livestock rules, including Bill 95.

But supporters on both sides point out serious issues awaiting in the aftermath of reform. Breeders say the restrictions will create a cost-prohibitive situation; animal groups counter that the Amish will pull out of the business when they lose the opportunity for quick and easy cash.

The toll on Amish communities will be significant, according to Ervin Raber. He estimates that around 60 to 70 percent of the families in his area stake their survival on income from breeding. "It's going to make a difference," he says. "There are house payments that are going to be missed."

Upheaval in the business could give rise to a new round of woes, rescuers say. If a number of breeders quit, countless kennel dogs will suddenly be homeless. One of the first actions by the proposed Kennel Authority would be the establishment of a rescue program. The fear, according to Kellie DiFrischia, is that without a clear outlet for mill dogs, breeders may simply let animals go or put them down.

She hopes to see the Kennel Authority work with Amish breeders to bring their operations up to the new guidelines. "Ohio has this black eye as being one of the worst states for conditions, so if you are a breeder in Ohio, you are going to want these standards set in place."

She knows, however, that the key to accomplishing that lies in opening communication and trust between groups that inhabit very different worlds.

Send feedback to [email protected].