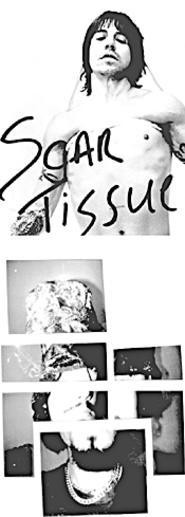

Anthony Kiedis's Scar Tissue is alternately a compelling and tedious portrait of the artist as a dope fiend. Working with Larry Sloman -- who co-wrote Howard Stern's Private Parts -- Kiedis, a mediocre writer, is given to using the same earthmother-New-Ageisms that pockmark his lyrics as frontman for the Red Hot Chili Peppers. ("I started to become aware that Flea . . . was not on the same heavenly ambient wavelength.")

Of course, most readers will be digging for dirt here: childhood memories of getting stoned with his dealer dad in L.A. or sleeping in the same bed with a naked Cher, not to mention a rise to fame that included the death of guitarist Hillel Slovak and more stints in rehab than Robert Downey Jr.'s. Where Scar Tissue succeeds is in its portrait of the slavering desperation of your garden-variety drug addict. Kiedis may pal around with Madonna, but in the clutches of heroin and coke addiction, he's just another loser holing up in seedy motels, busting out of rehab, turning his life around only to run it straight into the ground. The book ends in a glorious swell of 12-step euphoria -- a band that once used together now meditates together -- but what most readers will remember are the ungodly excesses of his past. Kiedis may be glad to be done with drugs, but as with the beautiful and volatile women he dates, he can't help romanticizing them.

It's hard to romanticize anything about drummer Tommy Lee's TommyLand, a numbingly idiotic book that might as well be written all in lower case, with emoticons after every sentence. Lee's story could be a cautionary tale about the dangers of drug use -- except, we suspect, he was always this stupid. The book begins with a conversation between Lee and -- no joke -- his own penis:

"Dick: No matter what you write in this book of yours, I promise you, people will buy it for one reason -- to find out how long I really am."

Okay, so his dick speaks the truth. As for the man himself, Lee offers such aphorisms as "A good idea to fire up your relationship is to drive down the highway at about 65 mph and have sex with your girl." Apparently he doesn't drive a standard. Mr. Lee also suggests that men shave their own pubes and have foursomes instead of threesomes (so no one's left out), and he claims that come tastes better if you drink pineapple juice beforehand. Worse, Lee has next to no insight (or memory) regarding his high-profile relationships with Pamela Anderson or Heather Locklear, although there is one figure from his past he remembers: "One thing I don't miss about being in Mötley Crüe is seeing Vince [Neil's] bloated, disrespectful, fucking ass every day." Oooh, burn. Except that Lee comes across as an unstable sex addict who stalks his way into girls' hearts. If you're curious about Mötley Crüe, we suggest VH1. If you're curious about sex, we suggest a more reliable source -- like the boys' locker room.

From Dave Navarro, former guitarist for Jane's Addiction and Red Hot Chili Peppers, comes Don't Try This at Home, which concerns essentially the same subjects: drugs, sex, and -- what's the other thing? -- rock and roll. But it's far creepier and very dark. Written in collaboration with journalist Neil Strauss, during a year in which Navarro wallowed in the depths of heroin abuse and paranoia, Don't Try This is part art project, part diary of a madman. It begins with a premise: Navarro places an old-fashioned photo booth in his Hollywood Hills home and takes pictures of all who enter. The book is scattered with these images, usually unidentified -- musicians, burnouts, Rebecca Romijn-Stamos.

More interesting, though, are the stuttering stories that accompany the photos, short essays by Strauss on navigating Navarro's erratic behavior, and conversations between Navarro and visitors about prostitutes and guitarists and his own slipping-down life. Navarro is a complicated person -- maybe a narcissist, maybe a little boy lost -- and he's obsessed with documenting his own life. Thinking that he's overdosed one night, he runs to get his camera to take a picture of himself. (In this context, his MTV reality series, made with current wife Carmen Electra, makes perfect sense.) Eschewing traditional narrative for 4 a.m. ramblings and torn-up suicide notes, Don't Try This paints a haunting picture of addiction -- one as scattered and incomplete as its subjects.

The much-anticipated Wilco Book makes no mention of frontman Jeff Tweedy's addiction to prescription painkillers. In fact, it stays mum on almost all of Tweedy's personal life. Instead, the book examines components of the band's world -- their loft, their instruments, their methods of songwriting -- in the hopes that these tiny snapshots will add up to a larger whole. So here we find pages upon pages of curious doodlings and photos of drumsticks, a scratchy old bass, National Geographic spines. We'd much rather read Tweedy's juicy tell-all. In lieu of that, however, we'll have to make do with the revelation that the drum in "I Am Trying to Break Your Heart" is actually a hubcap, and that Tweedy challenged himself to write A ghost is born entirely in third person. It's terribly self-indulgent, and yet it seems to be the way Tweedy knows how to communicate, like a guy who can't stop relating everything in his life to sports scores.

The book comes with a CD of hushed alternate tracks that are of interest only to hardcore fans, and in addition to the band's musings, the book also features two significant essays. Rick Moody (The Ice Storm, Demonology) makes an unsuccessful attempt to duplicate the band's looping, cryptic songwriting, which comes off only as pretentious. Far more lovely -- and comprehensible -- is an essay by Henry Miller, in which he speaks of the great joy of painting in watercolor. If there's a sonic metaphor for what Wilco is doing, it may be just that: a wash of sounds and textures, meant to make deep and lasting impressions, rather than perfect sense.