"Your name's Tay Tay, right?"

It was shortly after midnight on Nov. 1, 2010, at the abrupt end of a Halloween party gone wrong. Drunken backyard arguments became gunshots and blood loss, and now the cops were here. Dozens of friends and assorted cousins were fleeing into the neighborhood by the time Fourth District police officers Michael Keane and John Mullin responded to calls of shots fired, calls that brought them to a four-unit house on East 104th Street in Union Miles where Octavius Williams' father lived.

Casing the perimeter for an active shooter, the officers soon encountered Dennis Cole, a gunshot victim presently slumped against the side of the house, howling in pain. The officers radioed for backup.

Only a few people remained outside: Two men stood with Cole as he inspected the bullet hole in his chest. He fingered his back for the spot where the second shot had entered his body. A black Monte Carlo was parked behind the house, grazed by handgun rounds and left with a shattered window. Keane and Mullin tried to pry information from the man with the wounds. So, what exactly happened here?

Later, at the hospital, Cole would record a 0.27 blood alcohol level. Now, he was screaming. More officers showed up, and Cole joined the other two men in a flurry of simultaneous chatter, turning the madness of the evening into a babble of play-by-play pronouns and verbs.

"[I] asked if he knew the names," Keane said in court the following summer. "He knew them because they were all there for a party. Meantime three guys were talking at once. I got like the lady whose apartment it was, her boyfriend — her boyfriend's son shot him, nicknames, stuff like that. ... They said the guy's name that live there, his girlfriend lived there, was Ardy, Ardy's son. I know at some point I learned Tay Tay. I don't know if it was right then or later on, so ... ."

When Keane went upstairs to see about "Ardy's son," this Tay Tay character, he found a living room full of young children huddled near the window, watching the surreal nighttime activities below. Among them he saw an obviously taller male, standing out from the crowd of kids. He fit the vague description that Keane had jotted down from the ramblings out back: "juvenile, black male, tall, thin, maybe no shirt."

"Your name's Tay Tay, right?" Octavius Williams recalls Keane asking him. The kid was 17 at the time.

With little else to go on and a long night of undercover robbery and burglary detail still ahead of them, the officers arrested Williams and led him to a station car out front. A gunshot residue test applied on-site turned up negative, but the boy was nonetheless driven to the police department and later booked into Cuyahoga County's juvenile detention center.

Based solely on the blurted identification from Cole, an ID that was contradicted by other witnesses who insisted Williams was upstairs at the time of the shooting, the kid was indicted.

In July 2011, concluding a five-day trial, Williams was convicted of one count of attempted murder, two counts of felonious assault and one count of having weapons while under disability.

Cole had spent three months at MetroHealth Medical Center, recovering from wounds so grievous that physicians simply left the bullets in his body. He testified in court from his wheelchair. The gravity of the Halloween party's startling end was not lost on Judge Deena Calabrese, who sentenced Williams to 15 years in prison.

"It reminded me of an old-style Hatfield and McCoy sort of a shootout, a fight between two families that ended up — and I think that if Mr. Cole hadn't been injured so significantly, maybe none of us would be here right now," the judge said on the final day of Williams' trial. "Maybe things would have just been forgiven and forgotten, but ultimately his injury was so significant and I think he was so frightened as a result of being shot the way he was, that here we find ourselves now."

Williams walked out of prison on Dec. 17, 2019, not by early release for good behavior but by catching the good fortunes of a joint investigation by the Wrongful Conviction Project of the Ohio Public Defender's Office and the Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) of the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office. Enough palpable doubt had crept in since the jury convicted Williams that release from prison was the only move available to those pulling the strings of Williams' criminal case.

What we'd learned since Halloween 2010 was that Williams' older brother, Ricky, had run away from the party by the time police officers arrived that night. Everyone who played a role in Williams' convictions — except for Cole, mind you — said that it was Ricky who fired the shots in question, who committed the attempted murder, the felonious assault. It was Ricky who got caught up in the escalating arguments out back. Shortly after Williams' 2011 trial, in fact, Ricky finally came forward and confessed to shooting Cole. He submitted written affidavits and reiterated his confession on at least three more occasions.

In late 2019, wrapping up several years of investigative work on the story behind Williams' conviction, the CIU's internal review board cast a majority vote in favor of what the criminal justice system calls "exoneration," or "actual innocence." The CIU's independent external review panel concurred with a unanimous vote: Williams was innocent.

Prosecutor Michael O'Malley, who has the final say on these issues, no matter what the CIU boards vote to recommend, disagreed.

"You've got to use your human intuition and life experience to come up with the best decisions," O'Malley says. "What is justice in this case? I think in this particular case, we did the best we could. I think we did what was right."

Williams walked out of the Justice Center in downtown Cleveland and into an area as gray as the Brutalist building itself. He was free to go, O'Malley having decided there was ample evidence he shouldn't have been convicted, but not enough to declare his innocence. He wasn't guilty, but he wasn't not guilty.

The agreement that the system calls "judicial release" means that, technically, if we're playing by the books here, he's still guilty: In the eyes of the general public and the courts, he remains a convicted felon — and good luck landing a job or a rental agreement with that hung around your neck.

Williams was strapped with an ankle monitor and a 30-day curfew (get back home by 8 p.m.), as well as a two-year stint on probation. Any wrong move in that time will send him back to prison for the remainder of his original sentence, a sentence that nearly everyone involved except for O'Malley thinks he should never have faced in the first place.

Williams served 3,091 days of that sentence before this turn of events, this turn of fortune that doesn't quite scan as a full 180. He was a teenager when a man was shot at a Halloween party in Cleveland, and he was tried as an adult because he turned 18 before his trial began. In prison, he drifted through those nine years on the top bunk of prison cells that could never be home. Now, at 27, he's back home, yes, but robbed of his past and handcuffed for his future.

So, what is justice in this case?

* * *

At 17, Williams' life was basketball. He was playing on his high school team, angling for a dream job in the NBA in the mold of his hero, Kobe Bryant. He could shoot one hell of a three-pointer. It served him well enough in the yard once he landed in prison, but, he still wonders, where could that shot have taken him? What did life have in store for him?

In October 2010, his father, Arden Terry ("Ardy" to friends and, apparently, in court transcripts), told the family that he'd be throwing a Halloween party. Costumes. Good food. DJ on the turntables. He and his girlfriend gathered the kids from both families and set up a big bash. This wasn't unusual; Ardy's house was a hangout spot, as several families members explained in court.

Williams stayed at his mom's place back in those days, but he fairly split his time between both houses on the near-eastside of Cleveland. School and hoops were an equal distance either way. "Basketball was like my life, for real," he says. "It didn't matter if it was raining or if it was slushy snow on the ground, I'm always outside bouncing the ball. That's how to get your handles up. My mother was like, 'Tay-Tay, get in the house! You're going to get sick!' I'm like, 'All right, ma! Just give me 10 more minutes!' I loved it with a passion. I still do love it with a passion."

The party was by all accounts unremarkable for a while. Everyone was having a good time until it became a bad time. Williams' sister, describing in court the rapidly developing tension at the party, said that she could see some of the guys gathering out back. Voices getting louder. Accusations. Something involving the younger women at the party? Then: Her own brother, Ricky Williams; Demarcus Thomas; and Larry Johnson all shooting at one another. A man named Cedric Johnson took a bullet in his leg. Then a man named Dennis Cole, apparently approaching the shooters in an attempt stop the violence, took one in the front and one in the back.

"Everybody was scared," Williams' sister said, describing her retreat deeper into the house. Williams helped round up the younger kids and herd them into the living room, placing several walls between them and the alarming climax outside.

Keane and Mullin arrived, followed by more police officers. They found Cole, bellowing, his own blood pooling around him. Men and women dashed into cars and tore off into the neighborhood. Upstairs, they found Cedric Johnson nursing his leg; some of the officers helped get him down to an EMS vehicle. Then, Keane encountered their suspect.

"Your name's Tay-Tay, right?"

Downstairs, the police officers administered a gunshot residue test not only to Williams but also to fellow party attendees Darnell Calloway and Demarcus Thomas. In Thomas' case, the test turned up positive. Williams' test results — negative — didn't dissuade the officers from tagging him as the suspect.

By then, the house was silent. Cole was on his way to the hospital. Williams was on his way to the police station. His brother, Ricky, was on his way out of the narrative entirely, having fled the house right as the cops first arrived. The party was over.

As the next few months slogged onward, little happened in the way of a meaningful investigation. Detective Joel Campbell reportedly had Ricky Williams in mind as an alternate suspect, but it's unclear what came of the vague leads he was picking up. "I received some voicemails," he said in court. "I never really spoke with anyone in that regard. I believe there was some family members, and that I was never able to contact them concerning that or never developed any evidence in that regard. ... Through his father I indicated to him that I would like to speak to Ricky, if he wants to contact me at some point, and I never made any contact with him."

The jury didn't have much to work with. Keane admitted in court that he hadn't known that Ardy had multiple sons. Without asking the pertinent questions, why would he know such a thing? When he gathered his information from Cole and placed it next to the stray nickname that fell into the conversation, that was more or less the end of it.

Fifteen years. Gavel.

Weeks later, Ricky finally spoke up.

"Shortly after the party ended an argument occurred outside the apartment complex between my father Arden Terry and Larry Johnson," he wrote in jagged cursive in 2011, soon after his brother's conviction. "They had a few words back and fourth but once the argument reach the back of the apartment I was right in front of the back door and all of a sudden Larry Johnson started shooting towards me and my father's direction and shortly after Dennis Cole ran at me and punched me in the eye and I pulled out my gun and shot him out of fear for me and my families lives because shots were being fired at us first."

Ricky went on to confess to the crime at least three more times, including during a lengthy interview conducted in 2017 by Jose Torres of the CIU and Joanna Sanchez, Williams' attorney for the past three years.

After he began to tell his side of the story, he soon picked up his own case. In 2013, Ricky was convicted in a separate case of involuntary manslaughter and aggravated riot after pleading down from aggravated murder and felonious assault charges in Cuyahoga County. He's been in prison ever since.

* * *

The National Registry of Exonerations at the University of Michigan lists 2,549 exonerations in the U.S. since 1989. Of those, approximately 29 percent are tied to some form of mistaken eyewitness identification.

These cases prove particularly troubling in how the courts evaluate claims of wrongful conviction. In some instances, DNA evidence can cut clearly and persuasively through the past with certainty. But placing witnesses back on the record to recant testimony or change their interpretations of events isn't as simple in convincing judges to rewrite convictions.

"While history has afforded us the luxury of clarity over the participants and their actions at the fabled O.K. Corral, the same cannot be said of the events surrounding the situation arising on October 31, 2010, in the backyard of a Cleveland area residence," a three-judge panel wrote on behalf of the Eighth District Court of Appeals in 2012, upholding Williams' conviction. "The case ultimately rests on Cole's identification of Octavius as the shooter. After weighing the evidence and considering witness credibility, we cannot say, based on a review of the entire record, that the jury clearly lost its way and created such a manifest miscarriage of justice that the conviction must be reversed."

Cole was the only witness to name Williams as the shooter, but the circumstances don't provide the clarity that the Eighth District judges may have been seeking. On the night of the shooting, Cole recorded a blood alcohol level of 0.27. When questioned by Keane and Mullin, he stated only that he knew who shot him. At MetroHealth, after sublimating into consciousness once again, he was presented with several photo lineups: two containing Octavius' photos and one containing Ricky's photo. Neither lineup contained photos of other men from the party. He picked Octavius and remained the only person to do so.

"He knew who I was, out of all the rest of my brothers," Williams says, telling Scene that he was the one brother who hung around his dad's place the most, who ran into Cole often in the months leading up to the party. "He knew who I was, because I was always there. To this day, I still feel like that's the only reason he said my name, because I was the only name that he knew."

At the trial in 2011, the other gunshot victim, Cedric Johnson, reiterated that he never knew who shot him. (When Johnson was presented with a photo lineup, he picked Ricky.) Three other people insisted that they'd been sitting with Williams upstairs while the arguments reached a fever pitch below. The overwhelming opinion of those at the scene was that Williams was in the house, far from the source of the party's horrific gravity.

In October 2010, as Halloween ticked coolly into November, Joanna Sanchez was in her last year of law school at the Ohio State University and working as an intern with the Wrongful Conviction Project, part of the national Innocence Project. She'd harbored an interest in criminal law since her days as an undergrad at Ohio University, studying psychology and sociology and learning the human mechanics of how local government decides who is guilty of what.

In prison, Williams filled out the Wrongful Conviction Project's application. In 2014, he heard back from the office, when an investigation into his case began. The Ohio Public Defender's Office dispatched a law student to follow up on the case —reading through the details on the record and retracing the steps of any previous investigation. This included conducting new interviews with Williams and other family members who'd been at the party, like his brother Ricky. Sanchez took on full representation duties for Williams in 2017.

"We're certainly thrilled that Octavius is home, but we very much view that as just the first step in this process," she says. "We take cases where we believe the person is absolutely innocent, and we believe that in Octavius' case. We do intend to keep fighting for his full exoneration."

This is the first time that Sanchez has had to wade into the gray area between judicial release and exoneration. The disparity between the CIU's votes on Williams' case and O'Malley's presentation of it to the court is not easily understood, and it engendered disappointment in the prosecutor's office, sources tell Scene.

"The overarching thing that's emerged for me as I've done this work is the human factors that lead to wrongful convictions," Sanchez says. "Our criminal justice system is a system run by humans, and humans are fallible. We make mistakes. We have our biases. All of these things impact how we act within the system. When you look at the causes of wrongful conviction, it's human errors. It's mistaken eyewitness ID. It's perjury. It's faulty forensics. It's things like that — and it's people acting in ways with their own motivations that come into play. You're dealing with that same thing when you're trying to overturn a wrongful conviction. It's hard to see our own mistakes and it's hard to see our own errors, and so there are a lot of obstacles when you're trying to overturn one of these wrongful convictions to getting the relief that you're seeking."

On Jan. 21, 2020, Sanchez revived Williams' September 2011 motion for a new trial. (As of Feb. 3, the state had not yet filed a response.) At the time of the original motion, the state's attorneys had filed a response and opposed the motion. The following month, in October 2011, Williams' defense attorney was suspended from practicing law in Ohio.

The key in asking for a new trial, as in this case, is that new evidence must not merely contradict evidence that has come before. A new confession that takes a jab at what someone said 10 years ago isn't going to fly. But new evidence that aligns with the story painted by the defense — new evidence that would tilt how a jury sees the course of events playing out — that's where attorneys like Sanchez can find an opportunity to return to court and reignite the state's litigation of someone like Williams.

Here, that evidence is Ricky's confession. All three of them, to be specific. In 2015, he wrote a more detailed narrative in a certified affidavit:

"On Oct. 31, 2010, I Ricky Williams attend a family party. We all was having fun until Larry Johnson came in the house party all drink. Larry was tryin to start fights with people in the house. So my dad told Larry to go outside and get some air wen Larry went outside he seen my uncle outside talkin to his older neice. So Larry got mad and pull out a 22 caliber gun and started to shoot at my uncle so my dad heard the gun shoot's and he run outside so when my dad got out there he seen Larry Johnson shootin at his brother that wen my dad told Larry to put the gun down by Larry said No and point it the gun at my dad and he started to shoot again. That wen I pull out a 32 caliber and started 2 shoot at Larry. Because me and my family like was in danger. That wen Dennis run up on me and hit me with his hand in my face as I was shootin and that how Dennis got shoot. He run in the bullets. I never attend to shoot Dennis and when I heard Dennis was shoot I had left.

"Only way why I haven't came forward is because I was scared to go to jail for something I never meant to do. I never meant to hurt no one. Now I'm comin forward to help my lil brother get out of jail for something he never did."

Williams didn't find out about any of this until later. "Them people came and talk to me and I told them everything so you should be good lil bro," Ricky wrote in a 2015 letter to his brother. "But anyway they mail run slow down here that's why you haven't heard from me and I been tryin 2 fight my case etc. and I love you and miss you bro." As the wrongful conviction investigation got under way, Williams was advised against reaching out to Ricky and communicating in any way that could compromise the research into who did what at the Halloween party — and who said what in the years since.

"I'm close with all my brothers, and I'm still close with him," Williams says. "I was upset that I couldn't write him, because that's my brother. I know what he's going through. The reason why is because I was in there too."

* * *

Michael O'Malley was elected prosecutor in 2016. Not for nothing, he was the only candidate to file for the March 17, 2020, primary ballot, all but ensuring another four years of uncontested rule at the helm of the county's prosecuting authority.

In 2014, the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office started its Conviction Integrity Unit, part of a growing trend in county jurisdictions across the country.

"All of us in the criminal justice system have an obligation to seek justice and to seek the truth. We want to convict the guilty, not the innocent," former prosecutor Timothy McGinty said as he announced the unit's conception. "So if we learn we have convicted the wrong person, we want to correct it. We always want to have open ears on the subject of innocence."

The CIU functions as an extrajudicial arm of the prosecutor's office that may reach into the past and determine whether a defendant caught a fair trial. Did something go wrong? Is there a legitimate opportunity to revisit a trial court's decision? What we can do to fix this? The unit evaluates cases differently than the courts and, when presented with compelling reasons to re-evaluate a case, will conduct a further investigation. (The downside, at most CIUs, is that staffing is nowhere near the level necessary to tackle the volume of cases that need addressing, nor to do so in a prompt manner.)

After the investigation, when a case is cleared for some sort of decision from the CIU, the internal conviction integrity board and an external independent review panel take votes on the question of "actual innocence." The CIU board comprises eight attorneys (most of them being assistant prosecuting attorneys from within the office). The independent review panel comprises at least four members, "including, but not limited to, accomplished lawyers, community leaders, civic leaders, residents, business leaders, clergy, and/or legal scholars/experts," according to CIU documents. The county prosecutor has the final discretionary say on whether the board's or panel's recommendation is pursued.

The investigation into Williams' case spanned "at least 14 months," Russell Tye, the attorney who heads the county's CIU, said at the Dec. 17, 2019, court hearing. "We are in agreement with this motion that was filed by Ms. Sanchez, and we don't have any opposition to it whatsoever. And in fact, we are in agreement by way of compromise, as the court puts it."

The compromise lands somewhere between Williams' efforts toward full exoneration, including the CIU's internal and external panels' votes, and the current result offered by O'Malley in December 2019. He did not oppose Williams' judicial release, but he chose to stop short of declaring him innocent. Unusual territory for all involved. O'Malley admits that each case passing through CIU territory is different, a unique set of circumstances that must be met not only in a criminal justice capacity but in an almost philosophical capacity: "Oftentimes, it's difficult to ascertain without additional evidence exactly what occurred," he says. "Oftentimes, what you'll have in these cases is people changing statements from what they said 10 years earlier. You try to do the best you can in the interest of justice."

All told, the Cuyahoga County CIU has vacated three convictions since 2014, with Tye drawing a sharp contrast between that phrase and the phrase "exonerated three individuals." Each of those decisions has come under O'Malley's tenure. In 2017, the county vacated Evin King's 1995 murder conviction, using DNA evidence to right a wrong. In 2018, RuEl Sailor was set free from his 2003 murder conviction, a case that partially involved mistaken eyewitnesses testimony.

Sailor's case rings familiar now, with the CIU outwardly expressing support for his claim — and then delaying the decision for months. ("Stop giving him the run-around!" one protestor shouted outside the Justice Center in 2017. "How long does someone have to sit in prison once you've found out they didn't do the crime?") Hemming and hawing may not be part of the CIU policy, but it's a part of the process.

"In the end, I think we're all better off," O'Malley says. "I think in this particular case, we did the best we could. I think we did what was right. ... I've also learned that there is a growth industry of attorneys who are trying to harvest wrongful conviction claims." And so, when O'Malley asks, "What is justice in this case?" in a case like this, one answer is: incremental.

And, one could argue, that justice is incremental because of prosecutors like O'Malley who express some tepid opinions about wrongful conviction cases, despite saying most of the right things, and who represent the system's reticence to correct its mistakes.

He says that Tye tracked down Cole and discussed extensively the implications of Williams' judicial release while he, the shooting victim at the heart of this case, continued to maintain his insistence that a kid named Tay Tay shot him. Cole "wasn't jumping for joy," the prosecutor says, but "he understood." This, O'Malley and Tye say, is the tension that the CIU must navigate.

"I've got a victim who maintains that he's the guy who did it," O'Malley says. "I wanted to be progressive as far as these types of issues, but I can't be naive."

The National Registry of Exonerations paints an unclear picture of how successful the 59 CIUs in the U.S. have been. Just over 50 percent of those units have recorded any exonerations at all.

"The proliferation of new CIUs in the last year gives us reason to believe that the trend will continue, and that we will see even more prosecutors' offices undertaking efforts to identify and correct wrongful convictions that occurred in their jurisdictions," according to a 2018 report published by the National Registry of Exonerations. "Some are likely to continue to serve as little more than window dressing, but many show signs of serious commitment to robust conviction review."

With each case that crosses Tye's desk at the CIU in Cuyahoga County comes another shot at clarifying that picture. He points to those three cases in Cuyahoga County as a way of illustrating that each case is unique and, while we're on the topic, talking in absolutes isn't the intent here. "The traditional definition of exoneration is not what guides the unit," he says. When he says in court that the state and the defendants' attorneys "are in agreement by way of compromise," that's as close to a conclusion as the CIU is taking the case right now.

Everyone else made up their mind a long time ago as to who shot whom at that Halloween party in 2010. Williams says he kept his sanity from that day on only by telling himself that he shouldn't be here. In prison he'd recite his mantra: "'I'm not supposed to be here.' I said that everyday in there. I don't know how many times I said it a day. I wouldn't say it out loud. I said it to myself. I probably said it over — I don't know how many times. I know it's past a billion."

In the interim, the prosecutor's office and the Cleveland Division of Police placed the burden of elucidating the truth on a frightened family — Octavius, Ricky, their little siblings who watched through windows as their world shifted uneasily — and, one could argue, punished Williams for what other people failed to say at the right time.

O'Malley stakes the bottom line for us: "Is Octavius Williams exonerated? No."

* * *

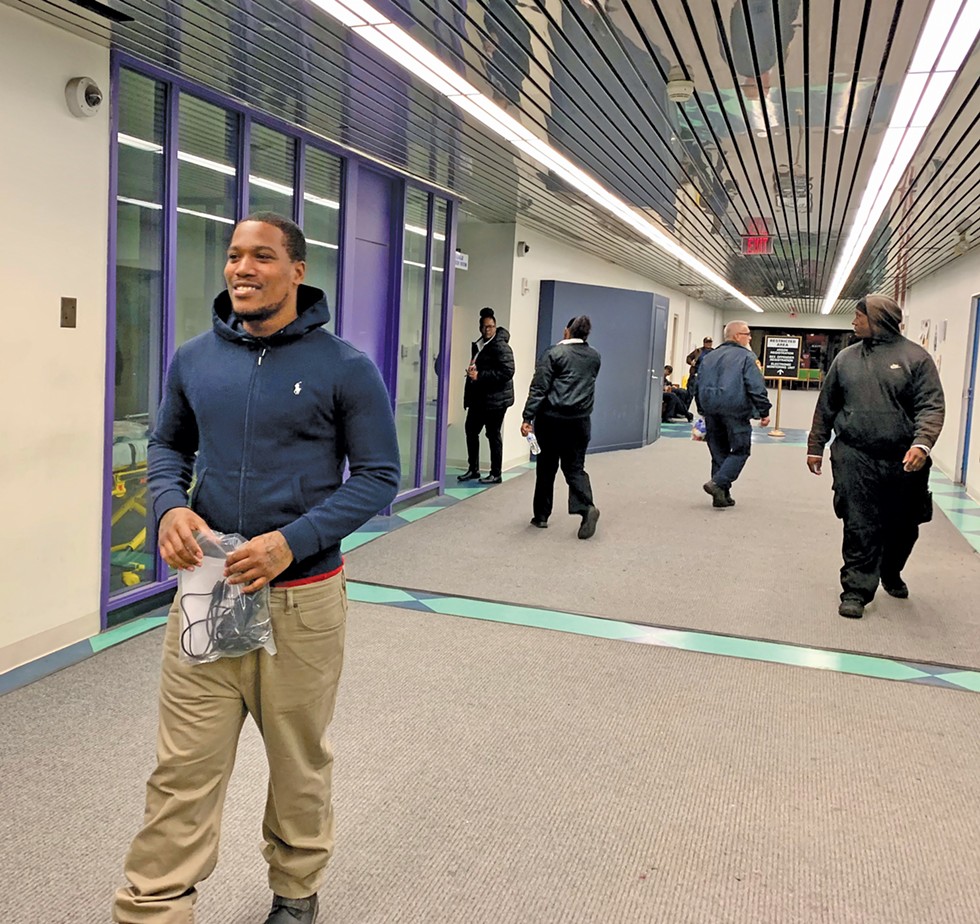

When Williams walked out of the Cuyahoga County Jail on Dec. 17, 2019, he walked into a cold, blustery evening on Lakeside Avenue. His attorneys from the Ohio Public Defender's Office in Columbus watched him draw a deep breath of fresh air and asked: Well, how are you feeling now?

"About 100 times better than I did in there," he said without hesitation.

He's still better, obviously, but better in a way defined and limited by how he was released, which is to say not fully.

Lately, Williams has been playing basketball at local rec centers, keeping his three-pointer as clean as ever — even when the ankle monitor gets in the way. But there are a lot of small moments that make up a day, and not all of them are fun. When his aunt accidentally slammed a door at her house, he flashed back to lockdown: Clang!

"I'm trying to get over all that stuff, but I can feel myself getting nervous when I'm around a lot of people now," he says. "It's like — it's still new to me. But as far as the holidays went, it was good. It was great. I definitely enjoyed it." He speaks in a rapid clip, almost rapping with a rhythm in his lilt, and he points out that this heightened sense of alert is a byproduct of his time in prison. The elongated stare. When he's watching you, his peripheral vision is doing work on the rest of the world, too. When he snaps awake in bed at night, he needs to remind himself that he's back in real life, and what does that feel like again?

In the first hour after he left prison on that crisp Cleveland evening in December, he came home to a big pan of lasagna his mom had cooked for him. "That's my favorite meal," he says. "I ate the hell out of it, too. It was crazy."

And if that's Williams' first task — setting a series of realigning actions to break the grip of prison on his mind — then it's a real chore to slot in time for the rest of life. Jobs. Housing. The baseline comforts of friends and family.

"Going through all that stuff, being put through hell the way I was, I didn't deserve none of that," he says. "Let alone with this felony on my name. That's a big stop sign for a lot of jobs."

Williams is staying at his mom's place, back where he grew up, and he bounces around family members' houses throughout the day. He has plans, he says, to visit Ricky in prison after he's formally exonerated by Cuyahoga County. As for when that will be ... "I'll never turn my back on my brothers," he says. "That's just how I've always been."

On a recent Sunday afternoon, he's hanging at his sister's Garden Valley apartment before following up on a job lead at a construction company on East 93rd. An interview at McDonald's on Broadway Avenue went nowhere fast.

The manager probed him on past job experience. He had none to speak of in the food service industry, but he cited some under-the-table work from when he was younger, breaking down houses as a teenager on the east side before he went to prison. He had a frank discussion about why he landed behind bars and what it was like to piece together a life after that. "She understood," he says. "I don't know if she's going to call me back."

A major issue here is the felony convictions dangling from Williams' name whenever he begins the process of applying for a job or seeking housing. This is what trails all former inmates, the criminal record. But in Williams' case, his judicial release is part of a broader story that gets a bit complicated when he tries to explain himself. The story isn't over yet, and it's hard to finish what you're saying if you don't know how it ends.

"I don't have no kids," Williams says. "I could have been done with high school, and I could have had at least two kids by now. Or I could be playing basketball. It doesn't matter. It would have been something of mine. Being in prison was not mine."