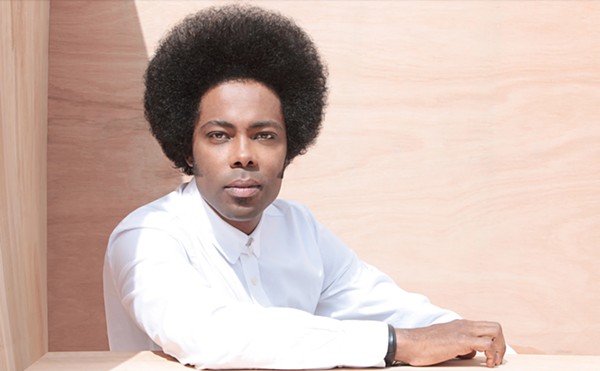

"San Diego is a really difficult place for music," Jenkins says from Atlanta. "There's a good scene in terms of people making good music, but as a city, it doesn't support the local scene so much. Right now, there's no all-ages club unless someone does something illegal at a warehouse, and that always ends up getting busted. There's been a lot of great bands, but we are the oddball. I've always played that role in the bands I've been in. I'm happy to play that part. "

Born in northern California, Jenkins was raised in San Diego, but spent three of those years on a Navy base in Italy. His first band, a group of friends from high school, was anchored by a deaf drummer the kids called D.P., short for "Deaf Punk."

"We really had no clue at all what the heck we were doing," Jenkins says. "We didn't even have a name for the band. We practiced for like three times, and we thought we were a band. We didn't ever play a show or anything."

His next band, Dark Sarcasm, fared better. It released an EP on the indie label Vinyl Communications, through which Jenkins met drummer Tom Zinser and bassist Armistead Burwell Smith, the rhythm section of a band called Neighborhood Watch. Along with multi-instrumentalist Tobias Nathaniel, they formed Three Mile Pilot in the early '90s. Sounding like a cross between Pink Floyd and Built to Spill, the group released Na Vucca Do Lupu, its debut, on Cargo/Headhunter Records in 1992 and garnered enough attention that Geffen signed the group. But by that time, Three Mile Pilot had already finished recording its second album, The Chief Assassin to the Sinister. Geffen wanted to release the record and, after letting Cargo/Headhunter put out an initial pressing in 1994, picked it up for reissue a year later and added three new tracks and different artwork.

For the next album, Another Desert, Another Sea, Geffen paired the group with producer Steve Fisk (Nirvana, Soundgarden). The label reportedly paid six figures in production costs and was so dissatisfied with the result that the album sat on the shelf for two years until Cargo/Headhunter bought the rights to release it.

"It was horrible," Jenkins says of the short-lived major label experience. "But it was a really amazing learning experience. It helped me learn about what I wanted to get out of music and taught me how full of shit a lot of that [major label] stuff is. They would suggest things that were outlandish and we wouldn't consider doing. They were trying to mold a band that was completely not able to be molded, because that's not what we're into."

As the Geffen debacle was unfolding, Zinser and Smith decided they wanted to take a break, so Jenkins and Nathaniel started writing songs with Clikitat Ikatowi drummer Mario Rubalcaba for the Black Heart Procession, which they originally thought would just be a Three Mile Pilot side project. But when Zinser and Smith backed out of a European tour at the last minute, Jenkins took Nathaniel and Rubalcaba overseas as the Black Heart Procession and played both bands' material. Not long after that, Three Mile Pilot disbanded.

Jenkins cites singers Johnny Cash and Tammy Wynette as influences, as much as '70s rock, and maintains that he's kept his interests as broad as possible. The Black Heart Procession's latest album, Three, supports his claims. The haunting, slow-motion piano of the opening track, "We Always Knew," makes Jenkins's vocals sound creepy and morose in a country murder ballad kinda way, while the rattling percussion and thick bass riff in "On Ships of Gold" builds into a trance-inducing squall.

"I bounce around so much [listening to different styles of music], I don't know if I'm a heavy metaller or a gospel singer," says Jenkins, who's also working on a book of fiction and drawings. "I'm not sure. I like anything that has some soul to it and feels passionate and good. Or anything that's completely funny and makes me laugh, I'm into."

Using a wide range of instrumentation that includes pump organ, clavinet, and saw, the Black Heart Procession creates dreary soundscapes that are a far cry from the punk stylings of Three Mile Pilot. Still, the chant-like vocals and progressions bear some resemblance to Three Mile Pilot, even if Jenkins would like to think that the Black Heart Procession is a much better outlet for him.

"With Black Heart, the initial rule is that we can't say no to each other," he says. "The idea is to do whatever you want to do. It was really fun to put a synth or weird sound on a song and to just do it. It wasn't four people arguing over what to do with a song."

After three full-lengths (titled One, Two, and Three) and two EPs ("Three Song Recording" and "Fish the Holes on Frozen Lakes"), the Black Heart Procession has finally started to get wider recognition. PJ Harvey, for one, has cited the band as one of her favorite acts, as has the indie band Blonde Redhead, whose vocalist, Kazu Makino, sings (via "long distance phone") on one track on Three. Looking back on his career to date, Jenkins admits it's rather ironic that he started doing his best work at the moment he was contemplating throwing in the towel.

"Toward the end of Three Mile Pilot, there came this point where I gave up giving a shit," he says. "I said, 'Fuck music, I give up. This whole music thing sucks. I'm just going to make a record, and I don't care if anyone listens to it or likes it.' The minute you drop those guards -- you can never drop them all, because it would be insane to say you don't care what people think -- and you get into the mind frame of doing what you wanted to do, things start coming together more. I don't know why, but that just came across in the music, I guess."