But when menial hourly employment is the only kind of work you can get to support your family, the issues become much more stark. How can a man earning $6 an hour put a deposit down on a decent living space? He can't, so he has to spend more money to live in a marginally sanitary motel. How can a woman with similar income and young children afford day care? She can't, so she turns her eight-year-old into a baby-sitter while she's at work.

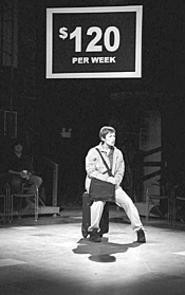

The working poor and their plight in benignly indifferent America is the subject of Nickel and Dimed by Joan Holden -- presented by Cleveland Public Theatre in association with the Great Lakes Theater Festival -- a dramatic adaptation of Barbara Ehrenreich's popular, identically titled nonfiction book. For one year, Ehrenreich embedded herself in the ranks of low-income workers, laboring as a waitress, a housecleaner, and a retail clerk to experience the workaday humiliations and the cash-flow challenges firsthand. And while her foray into desperate economic straits wasn't entirely genuine (she held on to some emergency parachutes, including her ATM card), Ehrenreich was able to convey with telling immediacy the cruel conundrums of low-wage life.

Holden's reworking hews closely to the source material, which doesn't always work dramatically. But this production sparkles like a restaurant's well-scrubbed kitchen counter, thanks to imaginative direction by Melissa Kievman and an ever-inventive six-person cast. Jill Levin is perfectly believable as Barbara herself, narrating her experiences as she moves from Florida to Maine and then to Minnesota in search of the primary punch-clock sensibility. Along the way, she shares with her co-workers cigarette breaks (one of the few job perks, and even that generates tumors) and hatred of control-freak corporate bosses.

Director Kievman's staging is continually involving from several perspectives. For one, she has created a theater-in-the-round space inside CPT's Gordon Square facility, so that the audience can observe itself as well as the action in the center. Indeed, the working poor are curiously invisible most of the time, even when they're standing next to us, and this production dissolves that barrier, if only for a couple of hours. The stage structure also suggests a Roman coliseum, where the privileged watch as doomed gladiators battle economically with capitalism's beasts of prey. In addition, Kievman and scenic designer Todd S. Krispinsky keep the action moving by mounting virtually all set pieces on casters, wheeling them in and out as in a well-oiled roller derby.

But the supporting players, all of whom play multiple roles, furnish much of the sting of Ehrenreich's discoveries and loads of the humor. George Roth is consistently surprising as, among other things, a barely fluent immigrant busboy, Barbara's clueless husband, and a selection of grubby supervisors. Equally flexible and talented is Nina Domingue, as an aggressively comical Puerto Rican cook and a slow-talking, slow-walking hotel maid. Tracee Patterson etches a couple of memorable characters -- in particular the sweet, helpful, but totally intimidated Holly, who is the pregnant "team leader" of the housecleaning crew. Nan Wray and Sheffia W. Randall also have fine moments as, respectively, a gimpy but game cleaning person and a born-again "Mall-Mart" shelf-stocker.

Since the play's structure is so episodic, there is little opportunity for any real character development -- a difficulty that is augmented by Barbara's continually breaking character to comment on the proceedings. In fact, in the second act, the entire cast drops the fourth wall and has a brief talk-back with the audience about the patrons' experiences cleaning houses or offices and their employing of others to do the same. This fragmentation means that, from time to time, Nickel and Dimed feels like loose change theatrically. Even with these minor quibbles and a dialogue pace that on this night was a bit spongy, the production is a triumph. Credit goes to CPT's James Levin and GLTF's Charles Fee for combining their companies' imposing talents on such a worthy effort.

So, after all is said and done, who is to blame for the awful lives of the working poor? As one character revealingly explains, it's no one's fault. It's all about the numbers: the profit numbers that drive corporations to deny their employees decent compensation and the bargain-price numbers that draw millions of customers through Wal-Mart's smiley-face doors.