With the nationally broadcast send-off for President George H.W. Bush only just in the rearview mirror, and with the calendar's impending turnover to 2019 just a few weeks ahead, it's that time of year when the notable deaths of 2018 will be aggregated and slideshow-ed for consumption on your favorite mobile device.

You will read about and remember Anthony Bourdain and Stephen Hillenburg and Aretha Franklin and Stan Lee and William Goldman and Paul Allen and Mac Miller and other luminaries whose deaths were of general and widespread interest. What's offered here is different. Yes, these people also died in 2018, but their deaths largely didn't vault from the obit pages of The New York Times or Washington Post, where notable deaths are chronicled in beautiful and regular fashion, or from the obit pages of the daily papers of cities where these folks lived and worked. Their endings may not have merited a CNN chyron or Twitter Moment headline, but that they were lesser known doesn't mean they aren't worth remembering.

GARY BURDEN

As an elder millennial, I sort of straddle two worlds: the analog and the digital. I didn't have a cell phone until I was a junior in high school, but I've been downloading music since the days of Napster and Limewire. That being said: I remember what it felt like to hold a CD, tape or record and cherish it in a different way than we do now — an era when we just pay $10 a month for unlimited streams of almost every album of every artist ever.

I specifically remember being in the gigantic Tower Records in New Orleans and flipping through the entire wall of darkwave/industrial CDs, mesmerized by how much of a collection they had. Or going home with a brand-new batch of music and sitting on the floor in my bedroom unraveling the album artwork and reading the lyrics along to the music.

It was quite a different age, and some of the folks who helped make it so were the geniuses behind some of those album covers.

Enter: Gary Burden.

If you dig classic folk-rock, you probably remember the cover of Joni Mitchell's Blue album, a close-up, high-contrast midnight-blue portrait of Mitchell looking down. It's melancholic and rich and, most of all, it invokes feeling in the viewer. Burden designed that. The former architect was actually a sought-after album designer starting in the late '60s for many a rock 'n' roller and folk artist including the Doors, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young and even current artists like Conor Oberst, who's probably best known for his work in the emotive indie-folk project Bright Eyes.

"Gary always wanted the album packaging to reflect the spirit of the music and the wishes of the artists as much as possible," Oberst said about Burden in a recent article in The New York Times. "He was often at odds with record labels when they sought to cut costs at the expense of what he and the artist had envisioned. Gary usually won those battles."

While studying architecture at UC Berkeley, Burden met Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas, who would ultimately be the one to turn him on to designing album covers for a living. "I met her and she asked me to do a remodel of her home in Laurel Canyon," Burden said in a 2015 video interview with NPR's World Cafe. "So she's the one who said, 'You know, Gary, you should make our new cover; you know how to design stuff,'" he said.

The rest, you could say, is history. After a lifetime of contributing his own art to the music community, Burden died earlier this year on March 7. No cause was given.

As time seems to slip faster beneath us and technology speeds the world up, Burden's death feels like a reminder to slow down and look at the details; feel the textures and edges and maybe sit with — and breathe with — a piece of album art. It'll most likely enhance the entire musical experience.

— Chris Conde

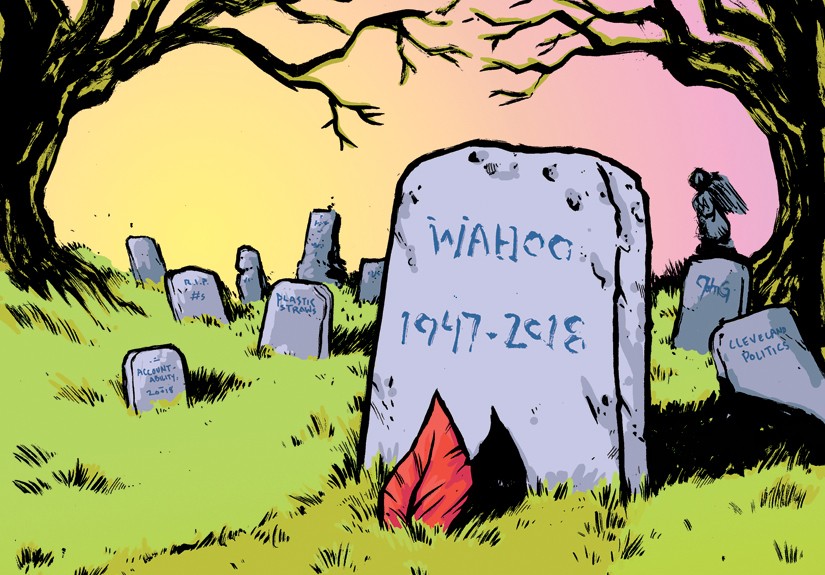

CHIEF WAHOO

The racist red-faced symbol that has adorned the sleeves and ballcaps of the Cleveland Indians' uniforms — not to mention the apparel and doodads of Cleveland baseball fans — since 1947, has succumbed at last to its inevitable fate, possibly timed to Cleveland's imminent date in the national spotlight with the 2019 MLB All-Star Game. The oft-floated and entirely plausible theory being that MLB commissioner Rob Manfred, a vocal opponent of Wahoo's continued use, told Cleveland the summer showcase would only be bestowed on the city if the offensive symbol was no longer around. MLB's very public announcement of deliberations between the team and the league on the Wahoo front in advance of the All-Star Game announcement lent a certain undeniable credence to the conjecture.

In recent years, the team had "scaled back" the use of Wahoo in favor of a primary "Block C" logo, but the image was still beloved among diehard fans, prominent in the team shop and regularly worn by the team.

Team owner Paul Dolan announced last year, though, that Wahoo at last would be eliminated, at least as an official logo on the team's uniforms. Given MLB's visible crusade, Dolan, who had over the years acknowledged Wahoo's problematic existence and its reception outside of the city, could at least save face with ardent Wahoo's supporters — many of whom now wear "Keep the Chief" or "Long Live the Chief" apparel to games — by saying it was Major League Baseball, not the Indians, who was to blame.

Last year, the logo was paraded around for the full season, an outlandish farewell tour for a symbol that most everyone outside of Cleveland has long acknowledged represents an enduring harm to Native American communities. It was and is a grotesque caricature that belongs in a museum, if not a garbage can.

Chief Wahoo first appeared in 1947, created by cartoonist Walter Goldbach, who was only 17 at the time. (Goldbach died in 2017.) The image was meant to "convey a spirit of pure joy and unbridled enthusiasm," at a time when Native American racism was still rampant. The team name was "inspired" by former Native American player Louis Sockalexis, in the sense that fans enjoyed taunting and jeering him for the duration of his very brief career, one cut short by alcoholism. That is the legacy that current Wahoo apologists so passionately claim to be honoring.

In 1951, the logo evolved into the Red Sambo still in use today. His death is mourned and protested by thousands of Clevelanders who believe that professional baseball has been infiltrated by snowflake social justice warriors and race hucksters who are promoting racism where none exists for their own political and financial gain.

It is unfortunately survived on the professional sporting stage by the Washington Redskins name and by dozens if not hundreds of similarly offensive logos and nicknames of high school teams across the country.

— Sam Allard

JUDITH LEIBER

If you can't connect the dots between the words "handbag" and "art," you're probably not versed in the distinctive work of Judith Leiber, the late Hungarian designer who took a signature concept — whimsical metal clutches adorned with Swarovski crystals and semi-precious stones — and ran with it in vivid fashion for decades while carving her own niche in the fashion world.

Born Judit Peto into a Jewish family in Budapest in 1921, she escaped the atrocities of the Holocaust — thanks in part to a Swiss letter of protection her father managed to obtain — and weathered WWII in an overcrowded apartment reportedly shared by 26 people. Although aimed for a job in the cosmetics industry, she instead broke the mold and became the first woman to work at the Hungarian Handbag Guild, where she perfected design and fabrication skills from the ground up. In 1945, while selling her own handmade purses on the side, she met Gerson "Gus" Leiber, a Brooklyn-born Army sergeant and modernist painter stationed in Budapest. By 1947, they were married and living in New York City.

In New York, she worked for handbag manufacturers and hit an early career high in 1953 when first lady Mamie Eisenhower arrived at the Inaugural Ball carrying a small, bedazzled clutch crafted by Leiber. Although the credit went to her employer (designer Nettie Rosenstein), this turn of events foreshadowed a trend of powerful women — from queens and movie stars to first ladies Lady Bird Johnson, Nancy Reagan, Barbara Bush, Hillary Clinton and Laura Bush — clutching Leiber's shimmering creations at high-profile events.

In 1963, the couple officially dove into the luxury handbag business together via Judith Leiber Inc., with Gerson on the business end and Judith handling design, fabrication and marketing.

In the decades that followed, Leiber took her playful, over-the-top aesthetic to the limit while challenging the confines of minaudières — decorated metal clutches only big enough to carry what she summed up as "a handkerchief, lipstick and a $100 bill." Collaborative efforts involving sculptors, painters, jewelers and artisans in the U.S. and Italy, Leiber's imaginative bags can take a year to complete and typically cost somewhere between $4,000 and $8,000, with made-to-order couture pieces ringing in closer to $20,000.

Beyond meticulous attention to detail and unapproachable price tags, one of the most remarkable aspects of Leiber's work is the juxtaposition of refined materials and techniques with nostalgic, child-like, even low-brow themes and concepts. Nevertheless her unapologetically extravagant minaudières — which have taken shape in dazzling cupcakes, ladybugs, cameras, cell phones, bundles of asparagus, Tutankhamen-inspired monkeys, burgers, fries and cocktails — have long been staples for A-list celebrities on often-humorless red carpets.

Although the Leibers sold their business in 1993 for a reported $16 million (Judith stayed on board as designer until 1997), the Judith Leiber brand is still intact and active, offering a reverent continuum of the 5,000-plus designs its co-founder created throughout her colorful career. In 2005, Judith and Gerson opened the Leiber Collection in Springs, New York, to "house their works of art and to chronicle their careers." While both are represented in major museum collections (he's in the Museum of Modern Art and the Brooklyn Museum, she's in the Smithsonian and the Met), the Leibers were thoughtfully showcased side-by-side in a trio of recent exhibitions while they were both in their 90s. After 72 years of marriage, Judith and Gerson died at home within hours of one another, both from heart attacks, on April 30, 2018.

As for the shimmering body of work she began building long before "bling" was even a blip on Merriam-Webster's radar, Judith Leiber presented her intricate evening bags as defiant status symbols, conceptual confections and wacky conversation pieces. All you need to enjoy one is a big bank account, a sense of humor to match and, as Leiber once suggested, an escort to carry the items that don't fit in your minaudière.

— Bryan Rindfuss

MIKE ARNOLD

Mike Arnold, better known as "Gus Gus Fun Bus," was run down in June by a stolen Ford F-150 in downtown St. Louis.

A pair of carjackers, fresh off pepper-spraying two women, apparently saw the bearded 54-year-old filming them with his cell phone, veered off the road and intentionally slammed him with the two-and-a-half ton truck, authorities say. They then crashed into a pole and were arrested within moments. In a way, it was a very St. Louis crime: stupid and needlessly violent with an element of small-town familiarity.

Arnold had become a favorite character in the city's food-and-drink scene. He worked for 30 years for AAA, but it was his alter ego as the gregarious driver of a fifteen-seat party bus and unofficial St. Louis ambassador that endeared him to brewers, restaurateurs and bartenders. He delighted in a good beer and gutsy young chefs who gambled on optimism. He used his ever-growing Twitter following to celebrate their work and introduce others to his favorite spots around town. In between, he offered congratulations on new babies, raised money for any number of causes and delivered weather reports with paternal advice to take care on the roads. At home, he was a father of eight who lifted sitting kids, chair and all, in his arms and danced them through the air, a husband whose wife woke to his voice: "Good morning, Angel." He and his wife first purchased Gus Gus Fun Bus because it was one of the few vehicles big enough to accommodate their blended family.

On the day Arnold was hit, he was downtown for a celebration of local food and chefs. He obviously knew about the city's darker side. Anyone who has spent any time here is familiar with the violence that can so easily overwhelm. The wickedness, the dog dumb brutality of his own death was a reminder of that St. Louis.

And if you want to fit his killing into that worldview, you can. But you will overlook what he saw here. You will miss the feisty beer-makers, the Cardinals' baseball games and the restaurants that get better every year. You will miss the fun.

— Doyle Murphy

DORCAS REILLY

She may not be a household name but Dorcas Reilly is a household staple: her iconic Campbell's Soup green bean casserole is served in more than 20 million American homes each Thanksgiving and, the rest of the year, acts as a quintessential comfort dish that can be popped in and out of the oven in less than 30 minutes.

Reilly, a 1947 graduate of Drexel University's Home Economics program, was one of the first two full-time employees at Campbell's Camden, New Jersey, home economics department, working in the test kitchen to develop new recipes.

Originally invented in 1955 as a "green bean bake" for an Associated Press story asking for a vegetable side dish made with pantry staples, the casserole calls for just six ingredients: a can of Campbell's condensed cream of mushroom soup, milk, soy sauce, black pepper, green beans and crispy French-fried onions. It was a wholesome home-cooked dish crafted in an Atomic Age that celebrated canned goods and convenience cooking, but its combination of creamy, crunchy and salty has stood the test of time. Today, more than 60 years later, Campbell's estimates upwards of 40 percent of their condensed mushroom soup sales are used to make Reilly's casserole — the recipe is even printed on the back of the can.

"Dorcas would often share that the first time she made her famous recipe, it did not receive the highest rating in Campbell's internal testing," wrote the company in an October memorial for Reilly's passing. "Yet, it was her persistence and creativity that led to an enduring recipe that will live on for decades to come."

Reilly worked for the company off and on from the 1940s to the 1980s, when she retired as manager of the Campbell's Kitchen in 1988. In addition to her lasting bean legacy, she also invented hundreds of other soup-infused recipes including a tuna noodle casserole, tomato soup cake and tomato soup sloppy Joes.

In 2002, Campbell's donated Reilly's original recipe card to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia, placing her patented legacy alongside the likes of Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers and Steve Wozniak.

"I'm very proud of this," she said of the recipe in a Campbell's video, "and I was shocked when I realized how popular it had become."

— Maija Zummo

GLENN SNODDY

Glenn Snoddy's contribution to the world of music wasn't through a song or a style of playing. It was more like he helped discover a new color.

A recording engineer in Nashville in the early 1960s, Snoddy helped capture and recreate what is commonly called "fuzz tone," the distorted, overdriven effect that helped shape the sound of modern rock 'n' roll.

And it was all, quite literally, by accident.

Already a recording veteran (he'd worked on pivotal sessions for Patsy Cline, Hank Williams and Johnny Cash), Snoddy was manning the console for a session with producer Don Law and country singer Marty Robbins, who was recording his 1961 single "Don't Worry." A broken amplifier that the bass was running through created a dirty sound about halfway into the recording that caught the attention of everyone working on the track.

"The transformer in the amplifier blew up," Snoddy told Murfreesboro, Tennessee's Daily News Journal in 2016 about the happy accident. The bassist (country and rockabilly session guitarist Grady Martin) reportedly wanted to redo his part, but Law and Snoddy insisted it remain.

After its release, "Don't Worry" went to No. 1 on Billboard's singles chart and musicians in particular loved the sound. Snoddy says Nancy Sinatra was in Nashville and wanted that exact sound for a recording session, but by that point the original "broken" amp had completely died. So he began figuring out how to re-create the fuzz, designing and building a preamp effects box to capitalize on the curiosity. He sold the design to Gibson, which turned it into the Maestro Fuzz-Tone FZ-1, the first commercially available guitar distortion pedal.

While the distorted guitar sound was pioneered by players like Howlin' Wolf guitarist Willie Lee Johnson and Link Wray (most notably on the revolutionary 1958 instrumental hit "Rumble") in the decade leading up to his invention, Snoddy was the first to capture that fuzzy lightning in a bottle (or, rather, box). The Gibson pedal (which initially sold for $40) wasn't an immediate hit and the company ramped down production of them until 1965, when Rolling Stones' guitarist Keith Richards used his FZ-1 on the band's seminal hit, "Satisfaction." Gibson sold 40,000 pedals in the wake of that song's success, after reportedly shipping a grand total of three over the course of the previous two years.

The fuzz tone sound became the foundation of '60s and '70s rock 'n' roll, leading the way for other popular pedals, including the Fuzz Face, beloved by Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend, and the Big Muff, which saw a revival in the late '80s/early '90s and became the key to the guitar sounds of bands like Mudhoney, Smashing Pumpkins and many other alternative rock acts of the time.

Snoddy, who'd later open Nashville's Woodland Sound recording studio (home to many important sessions, including the one for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band's "Will the Circle Be Unbroken"), died on May 21. He was 96.

— Mike Breen

TED DABNEY

In the beginning was a word. And the word was pizza.

Pizza parlors, to be exact — the ones lit by the blinking screens of arcade cabinets and populated by animatronic critters. In the mid-1960s, such establishments only existed in ambitious schemes cooked up by Ted Dabney and Nolan Bushnell, two friends then employed as engineers by California-based electronics company Ampex.

Dabney agreed to join Bushnell in his business venture, which combined the former's technological and electronics expertise with the latter's unbridled creativity and experience working as a carnival barker during college.

Unsurprisingly, the duo's initial efforts failed to bear the intended fruit (or dough, for that matter), but they did mark the genesis of electronic gaming as a cultural institution. What started out as a far-fetched dream would soon become a household name: Atari.

At the time, coin-operated arcade cabinets were largely analog machines: pinball, fortune tellers, Skee-Ball. Dabney and Bushnell were intent on replicating the mechanical complexity of these games first on a computer, and later on a television set. Programming and buying computers was cost prohibitive, so Dabney — inspired by how a TV set's vertical and horizontal controls move the picture back and forth — devised a way to move digital shapes across a screen using a universal platform that was cheaper to build and easier to manage and store.

"Ted came up with the breakthrough idea that got rid of the computer so you didn't have to have a computer to make the game work," one of Atari's first employees Allan Alcorn, told The Dallas Morning News in June. "It created the industry."

Bushnell pitched the new motion circuit technology to arcade manufacturer Nutting Associates, who helped the duo produce the first-ever commercially available coin-operated cabinet video game, Computer Space, in 1971.

The sci-fi themed game netted Dabney and Bushnell enough royalties to found their own company, first called Syzygy and quickly renamed Atari. The company broke into the mainstream in 1972 with the release of Pong, a simplified departure from Computer Space that simulated table tennis with two lines and a dot. By the end of 1974, Atari sold more than 8,000 units of the game at $937 a pop.

Unfortunately, Dabney reaped a much smaller reward than his partner. He learned that Bushnell had applied for a patent without his consent, submitting Dabney's designs under his own name. Bushnell's charisma pushed Dabney to a lower rung of Atari, leaving him frustrated enough to sell his ownership for $250,000 in 1973.

Disillusioned by the perils of success, Dabney largely bowed out of the industry. In the meantime, Bushnell pushed Atari into living rooms with a series of video consoles. In the late '70s, Bushnell enlisted Dabney to help develop a new venture — a restaurant-slash-arcade called Pizza Time, later renamed Chuck E. Cheese's. After further disputes split the pair up again, Dabney retreated from the entertainment industry for good.

Dabney died of esophageal cancer on May 26.

— Jude Noel

VLADIMIR VOINOVICH

By the time of his death, Vladimir Voinovich was never mentioned without some variation of his title: satirist. Sometimes it was "famed satirist" or even "master satirist." But the Russian writer, who spent his life alternatively fleeing and critiquing his homeland's leaders, told interviewers that he found the label exasperating. He saw himself as a realist.

"What I describe here is only what I saw with my own eyes," Voinovich writes in the introduction of his dystopian epic Moscow 2042.

Of course the book, described by one reviewer as "the Soviet Catch-22," is a ridiculous piece of fiction. The novel follows Russian dissident writer Vitaly Karsev, who essentially functions as Voinovich's stand-in, as he bumbles his way into a time-traveling expedition 60 years into the future. He arrives in a Moscow governed as a city-state by "pure Communism," a system wherein bathrooms are under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Natural Functions and newspapers are printed directly on toilet paper.

Above it all is the Generalissimo — a strongman keeping the population under control on the combined strength of religious dogma, a ludicrous cult of personality and the secret police.

The book was hit in the West when it was published in 1987 (it was banned in Soviet Russia). Decades later, contemporary scholars noted that the novel's dystopian merger of the KGB, the Communist state and the church foreshadowed the rise of Vladimir Putin, creating a reality with odd parallels to the fictional Moscow of 2042.

Voinovich noticed the similarity too. "I think it's pretty close," he admitted to The Daily Beast in 2015.

By then, he had already lived many disparate roles. Born to a Jewish mother and journalist father, he served as a loyal Soviet soldier in World War II, a wannabe poet under Stalin, a dissident writer under Khrushchev and then a satirist in exile in West Germany, where he penned Moscow 2042. Welcomed home during the presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev, he finally attained acceptance in his own homeland.

And then, like an absurdist plot in one of Voinovich's own works, Putin took control. Once again, Voinovich became an outspoken dissident, as the author rebuked the regime's repression of the media and political opponents, as well as the war in Chechnya.

Indeed, Voinovich managed to live long enough to become his own sort of time traveler. In his final years, he witnessed a backsliding Russia controlled by bureaucrats who projected breathtaking confidence in their leader, even as the country's hard-won freedoms unraveled under that leader's fist.

"Next time, I'll write a utopia," Voinovich joked to an American crowd a few years ago. "People keep saying that all the bad things I write come true, so I'm going to write something good."

Instead, he suffered a heart attack. The master satirist died July 28. He left his prophetic gifts for the next generation of dissidents and trouble-makers — and stories of comic authoritarianism that, with each passing headline, seem less and less fantastical.

— Danny Wicentowski

WILLIAM SHEARER

It was 1979 when Dr. William Shearer first met 7-year-old David Vetter, the Texas boy who was born without an immune system and lived in a series of NASA-designed plastic bubbles.

Many years later, Shearer recalled that first meeting in his blog. "He immediately put his arms in the gloves extending from his plastic isolator system to shake my hand and began quizzing me to make sure I understood that he was special and was competent enough to care for him," Shearer wrote.

Theirs would be a brief relationship; David died in 1984 at age 12 after an unsuccessful bone marrow transplant in an attempt to cure him of his severe combined immunodeficiency. Despite its brevity, the relationship would have a lasting legacy.

"He was like his father at the hospital, another dad," David's father told The New York Times. "They had a real strong rapport, and David loved him."

Shearer died this October from complications from polymyositis, an inflammatory disease that causes muscle weakness. Born in Detroit in 1937, he earned a bachelor's degree in chemistry from University of Detroit and a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Wayne State University, and graduated the Washington University School of Medicine in 1970. He later served pediatrics and immunology residencies in St. Louis before moving to Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, where he treated David.

David's was a lonely life. His older brother died from SCID, and his parents knew if they had another boy there was a 50-50 chance he could also have the hereditary disease. As soon as he was born, David was placed into his first plastic bubble. Any objects like toys had to be sterilized and placed through a series of air locks, and he could never touch another human.

Under Shearer's care, the case of David — a handsome boy who loved Star Wars and the Texas Oilers — captivated audiences around the world, with Shearer serving as its face. While Shearer often remarked upon David's resilience, observing David's despair at living in isolation — he reportedly had recurring nightmares about his condition — caused him to debate the ethics of keeping the boy trapped in a plastic cage. At one point, he suggested removing David from the bubble and trying other treatment methods, but his parents pushed for keeping him until a suitable bone marrow donor could be found.

In 1984, Shearer performed the long-awaited procedure. It didn't work, and David soon became sick from a lymph node cancer caused by an undetected lymph-node virus in the marrow. He lived his final 15 days outside of his bubble in a hospital room, where his mother kissed him for the first time.

On Feb. 22, Shearer appeared on television to announce David's death, which he would later call one of the most difficult times of his life. But his story with David wasn't over: With samples of David's blood, Shearer determined that David died from an infection from the Epstein-Barr virus, and later identified a gene that causes immune deficiencies. His discoveries would allow for a test for the condition in newborns. Thanks in part to Shearer's research, children with immune diseases are now able to live without plastic bubbles, and today more than 90 percent can be successfully treated with bone marrow and stem cell transplants within their first 28 days of life.

After David's death, Shearer founded the David Center at Texas Children's, a wing focused on treating immune diseases named in honor of his former patient and friend. He later focused his research on HIV and AIDS, participating in studies that led to the treatment and prevention of HIV and AIDS in children.

"People often ask what's the measure of someone's life, but very few people stood as tall as David," Dr. Shearer told The Houston Chronicle in 2009. "More than any scientist, he taught us by his life."

— Lee DeVito

THOMAS BOPP

Thomas Bopp wasn't looking for a comet when he peered into a telescope on Saturday, July 22, 1995. In fact, he wasn't looking for anything. By day, the 47-year-old worked for a cement company, where he made a passing mention of his interest in astronomy to Jim Stevens, who ran an auto parts store in Phoenix. It was a hobby started when Bopp was just a boy growing up in Youngstown, Ohio, when his father gave him his first telescope. Stevens, it turned out, was also interested in telescopes. By night, the two became amateur astronomers, going stargazing with Stevens' homemade telescope in the Arizona desert, with Stevens serving as Bopp's mentor.

That was exactly what they were doing that night, when Stevens trained his lens on a cluster of stars in the Sagittarius constellation shortly after 11 p.m. Stevens was eager for Bopp to take a look. But what he didn't realize was he had aimed his telescope directly at an unidentified flying object — what Bopp would later describe as "a little fuzzy glow."

In reality, it was a 46-mile-wide hunk of ice 577 million miles away, hurling through space.

The stakes were high — comets are a coveted catch for astronomers, since they are conventionally named after those who discover them. But first Bopp and Stevens had to notify the Harvard University to officiate the discovery. This was not an easy task in the Arizona desert in the '90s.

After studying the object for several minutes to make sure it was not a star, Bopp got in his car and drove 20 miles to a truck stop to try to call Western Union from a pay phone to send a telegram to Harvard, because yes, you could still send telegrams in the '90s. The Western Union representative didn't have an address, so Bopp hung up and got in his car and drove home. Around 3 a.m., he barged into his bedroom, woke his wife, found the address in an astronomy book, and sent the telegram with the comet's coordinates.

The next morning, Bopp got a call from the International Astronomical Union. Unbeknownst to Bopp, another astronomer — a real astronomer, Alan Halle, with a doctorate in astronomy and everything — had also discovered the comet within minutes of him, and had already emailed the coordinates to Harvard from his home in New Mexico. But once again, the stars aligned for Bopp: By what he later described as "bizarre chance," an IAU associate director happened to be in the office that Sunday and received the telegram. The comet, formally designated C/1995 O1, would be named Hale-Bopp, after both astronomers.

Bopp quit his day job to attend to the media maelstrom that followed. In 1997, the comet reached perihelion, or its closest point to the sun. It lit up the night sky for more than 18 months, its long tail visible to the naked eye to millions of people in the Northern Hemisphere. It was the biggest, most visible comet since the Great Comet of 1811.

The comet brought some misfortune, too. In March, 39 members of a California death cult, Heaven's Gate, committed mass suicide, believing their bodies would be transported to an alien spacecraft following the comet. In the spring, when the comet was the closest to the Earth, Bopp's brother and sister-in-law were killed by a car while photographing the comet. "This has been the best week of my life," he told National Geographic. "And the worst."

In recent years, Bopp worked as a shuttle driver at a Toyota dealership. He died on Jan. 5 at a hospital in Phoenix at age 68 from liver failure.

"I can find another job, but this is something that happens once in 10,000 lifetimes," he told Newsweek when he quit his job to bask in the glow of Hale-Bopp. The comet is expected to next pass Earth in 4897. — Lee DeVito

MARK E. SMITH

"If it's me and your granny on bongos, then it's a Fall gig."

A young Mark E. Smith started the Fall in the Manchester suburb of Prestwich after the infamous 1976 Sex Pistols show in Manchester, where the majority of attendees ended up starting bands the next day. It was the only time in his life that Smith would (unwittingly) succumb to rock cliche. He spent the next 40 years trying his best to dismantle rock 'n' roll and the music industry from the inside.

Though he looked like an ill-tempered postal clerk or substitute teacher, Smith was still punk and disorderly to the very core. With the Fall, he built a sound antithetical to the idea of musical proficiency, favoring instead spontaneity and creative tension, laced it with biting, clever, oft poetic lyrics and ended up with something every bit as inspirational as Gang of Four or Wire. The Fall were a band that (to their horror, perhaps) ended up inspiring generations of punk, new wave and alternative rock bands, and Smith became a de facto role model to those for whom the underground was more than just a temporary lifestyle choice. What other post-punk bands had enough cultural cachet to score a major label record deal (again), during the grunge revolution of the 1990s?

The unforgettable songs and anthems piled up like discarded ex-band members (over 60 strong, all told): "Totally Wired," "Mr. Pharmacist," "The Classical," "Hip Priest," "Glam Racket," "Ghost in My House," "Big New Prinz." Did you ever hear the Fall's cover of disco standard "Lost In Music"? If the albums aren't enough to slake your thirst, the Fall recorded 20+ live sessions with equally legendary British DJ John Peel over the BBC's public radio airwaves between 1978 and 2004.

Despite this fearsome productivity, Smith kept the Fall proudly "unprofessional." If during a concert Smith would drink himself into oblivion, unplug an amp (or five), mess up keyboard settings, change up the setlist, or recruit a new drummer fifteen minutes before showtime, what of it? As Smith himself barked, it's just "creative management, cock!" Smith was the Fall's only constant member during their 40-plus years of intense creative drive (they were contemporaries of Joy Division, just to put things in perspective): one or more albums a year, restless, constantly changing music, grueling touring schedules that have the logistical sense of darts thrown at a map of the world, and a bandleader who apparently hasn't eaten solid food in decades (subsisting on a liquid diet, as they say) dedicated to spontaneity, conflict, and uncertainty in day-to-day business affairs.

Smith anecdotes are almost as legion as Fall anthems — creating a cranky, effortlessly, yes, punk mystique that others would kill for. There's the apocryphal story of him catching some of his bandmates dancing to "Rock the Casbah" at an afterparty in the '80s and summarily delivering slaps to every offender, or when he almost single-handedly bottled Mumford & Sons offstage in the early '00s, the time he fired a sound engineer for eating a salad, fired a drummer on the unlucky percussionist's wedding day, or when he agreed to play on British chat show Later ... With Jools Holland with the contractual condition that the titular host not play "boogie-woogie piano anywhere near the Fall."

His never-ending embrace of chaos and tension had an ugly side to it; he could be vile and ugly to those closest to him. And yet, most remained loyal, believing in their flawed leader's vision, like the long-suffering Hanley brothers and, of course, Smith's most famous creative foil, guitarist and ex-wife Brix Smith. Brix was the most iconic member of the Fall, after Smith: a glammed-up American punk who contributed serrated guitar and unforgettable riffs to pivotal albums like The Wonderful and Frightening World of the Fall and The Frenz Experiment. Photos and video from her tenure in the Fall are essential and electrifying viewing, like transmissions from a strange alternate future. Their breakup was equally as seismic, though she rejoined the band for a brief time in the 1990s.

Smith died at 60 after a long battle with cancer, but was still doing shows, in a wheelchair, in the year before he passed, and never ceased writing and releasing music regularly. There will likely never be a pop star quite like him again.

— Matthew Moyer

ARNALDO "ARNIE" LERMA

Ever heard the story of Xenu, the galactic, genocidal alien dictator who, when faced with overpopulation troubles 75 million years ago, brought billions of his people to Earth to execute with a lethal combination of volcanoes and hydrogen bombs — leaving their disembodied spirits to cling to humans and whose removal could only be achieved through the teachings of the Church of Scientology? You can partially thank Arnie Lerma for that.

Arnaldo Pagliarini Lerma was born in Washington, D.C. on Nov. 18, 1950, to a mother who was an executive secretary to the Sudanese ambassador and a father who was a Mexican agriculture official — and who would soon divorce months after his birth, according to Lerma's autobiography. His mother was a Scientology official in the Washington, D.C. church around 1968, about three decades after American science fiction writer L.Ron Hubbard published the first texts that would form the basis of his new religion, Scientology. By the time Lerma joined Scientology at 16 at the urging of his mother, the church had been banned in several Australian states and stripped of its tax-exempt status by the IRS, which deemed it a commercial operation for Hubbard's benefit — though a U.S. appeals court would later recognize it as a religion in 1969.

Lerma signed a "billion-year contract" to serve on Scientology's elite Sea Org, a paramilitary force that some critics have described as a totalitarian organization, according to the Washington Post. But his status among fellow Scientologists changed when Lerma and Hubbard's daughter, Suzette Hubbard, fell in love (a claim that has been strongly disputed by the church). Lerma's entanglement with Scientology ended after other Sea Org members allegedly threatened to mutilate him if he didn't cancel his elopement with Suzette Hubbard.

Exiled from the religion that had been his home for years, Lerma became one of Scientology's fiercest critics. By 1994, he was posting public court documents involving the church online in the alt.religion.scientology newsgroup that "included testimony from former church officials who describe Scientology as a dangerous cult that brainwashes and blackmails its member and harasses defectors and critics," which earned him intimidating visits from men in dark suits at his Arlington home, according to the Post. In 1995, Lerma was the first to post the "Fishman Affidavit," which were documents submitted by ex-Scientologist Steven Fishman that included criticisms of the church and the doctrine of Xenu, which Scientology officials argued was copyrighted and a trade secret.

The church accused Lerma of copyright infringement and trade secret misappropriation, leading to a raid of his home by federal marshals, Scientology attorneys and technicians. The church's Religious Technology Center (RTC) sued Lerma, his service provider and Post reporters for quoting the affidavit. A federal judge found Post reporters had not violated copyright for quoting a publicly available court document, but Lerma was liable for a small number of non-willful copyright violations and ordered to pay a $2,500 penalty. The court, though, recognized it was convinced "that the primary motivation of RTC in suing Lerma, DGS and The Post is to stifle criticism of Scientology in general and to harass its critics," according to the 1995 ruling.

Lerma continued his crusade against Scientology on his website, Lermanet, which became a resource for other critics, and gave interviews on the subject in print news stories, television and radio.

On March 16, Lerma, 67, shot his wife, Ginger Sugerman, in the face with a handgun at their Georgia home before killing himself, according to the local newspaper, the Sylvania Telephone. Sugerman, 58, survived and told The Underground Bunker journalist and former editor of the The Village Voice Tony Ortega that her husband was taking oxycodone in his last months to deal with back pain and that his paranoia had increased. Ortega last reported that Sugerman, also a former Scientologist, was raising funds for her continuing surgeries and for efforts to honor Lerma's work, despite his last atrocity.

— Monivette Cordeiro

URSULA K. LE GUIN

More than 20 novels, not counting several of her earliest works that remain unpublished. A dozen books on poetry. More than 100 short stories, collected throughout multiple volumes. Seven essay collections. Thirteen books for children. Five volumes of translation, including the Tao Te Ching of Lao Tzu and selected poems by the Chilean Nobel Prize winner Gabriela Mistral. Oh, and a guide for writers.

Even stingily speaking, the career of author Ursula K. Le Guin — one of the 20th century's pioneering female science fiction and young adult writers — was prolific. Arguably her most enduring work, The Left Hand of Darkness inspired legions of genre-influencing writers, including contemporary savants such as Neil Gaiman, JK Rowling, John Scalzi and the widely acclaimed Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid's Tale. In fact, some critics would argue that no single work did more to upend the genre's seemingly predictable conventions than that of the Nebula and Hugo Award-winning novel, which imagined a world whose human inhabitants have no fixed gender; instead, their sexual roles are determined by context and express themselves only once every month. She would later refer to the story as a "thought experiment." "I eliminated gender to find out what was left," Le Guin told The Guardian in 2005. It remains one of the science fiction genre's academic touchstones to this day.

The only daughter of two anthropologists, Ursula Kroeber was born the youngest of four children in Berkeley, California, on Oct. 21, 1929. Her father, Alfred Kroeber, studied Native American tribes based in California, while her mother, Theodora Kracaw Kroeber, gained prominence in the same field with her acclaimed book, Ishi in Two Worlds, which chronicled the life and death of the state's "last wild Indian." Throughout her youth, with dinner-table talk of long lost worlds never far out of earshot, Le Guin would use her family's deep understanding of the world as a jumping off point as she immersed herself in mythology and classic fantasies, devouring the science fiction magazines of the day.

In 1951, she graduated from Radcliffe College before going on to earn a master's degree in romance literature from Columbia University in 1952. From there, Le Guin was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to study in Paris. While aboard a steamer set for France, she met the historian Charles Le Guin, whom she married a few months later. Later in life, the two would settle down and start a family in Portland, Oregon, where they lived in a Victorian house on a steep street just below the city's Forest Park. As the Paris Review noted during an interview with Le Guin in 2013, perhaps appropriate for a science fiction author and much like the worlds she'd bend within her fiction's narratives, their home appeared "larger on the inside than it does from without."

On Jan. 23, 2018, with one last conflict within a story to resolve, Le Guin passed away peacefully at her home in Portland. Her family did not cite a cause other than she had been in poor health due to old age. Le Guin was 88 years old.

— Xander Peters

EMILY DOLE

In the late 1980s, to climb to the top of the mountain of women's professional wrestling — albeit to reach what little there was there — was to be among the cast members on the hit sports show GLOW: The Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling. By most reasonable estimates, it was the first of its kind on television; hitting the airwaves in 1986, the all-female wrestling program consisted of women assigned outlandish, stereotyped alter egos, with names that couldn't have been further from the safe comforts of political correctness, like Matilda the Hun, Melody Trouble Vixen, Gremlina (she was only 4-foot-8), Babe the Farmer's Daughter and Big Bad Mama.

There, amongst the finest feminists of their time, you'd find the catalysts of what was then, and may still be, considered a flamboyant sub-culture. Considering the stress they put on their bodies, the female wrestling pioneers practically worked for free, making between $300 and $700 a week. There were no dental benefits that came with the job, just the risk of losing teeth in the process, nor was there medical insurance for the inevitable broken bones and bumps they'd suffer from time to time, from broken collarbones to concussions. For the most part, their only guarantee at the end of the day was pain and exasperation — and, when the bright lights dimmed and all the roaring chatter and commotion was said and done, when show time was over, the glory.

But among the many talented ladies who initially scratched the surface of women in professional wrestling, none of them are remembered quite like the one they called "Mountain Fiji." In fact, as legend has it, she never lost a match, which makes sense when you consider that she stood at 5-foot-11-inches and was billed as weighing 350 pounds. But even so, Mountain Fiji would have never been had it not been for the woman behind her larger than life persona: Emily Dole.

A proud Samoan American, an actress according to most definitions, an entertainer, an athlete by all means — Dole was by far the most recognizable character on GLOW, with her tree trunk-like arms and shoulders as wide as a volcano's outer rim. Prior to her time as a professional wrestler, Dole is remembered for her ability to toss a shot put over 50 feet as a teenager at Buena Park High School in California — a feat that's been repeated just twice since by other California high school girls. Later on, Dole qualified for two Olympic trials, where she finished fifth in 1976 and seventh in 1980.

In her final years, as documented in the Netflix original film GLOW: The Story of the Gorgeous Ladies of Wrestling, Dole dealt with a number of health problems, many of which were born out of her career in wrestling, and had been staying in an assisted living facility. In 2008, her weight had begun to get the best of her as she climbed up to 425 pounds, although she would later cut it back down to 235 pounds.

But like all volcanoes, though it had erupted hundreds of times within the wrestling ring, the fire inside her would inevitably lay dormant. On Jan. 2, 2018, Dole passed away from unknown complications. She was 60 years old.

— Xander Peters