Following Smith's lead, but secure in his own approach, McDuff quickly staked out his own territory: thick, wall-to-wall chords, understated support, and unhurried bluesy solos that fill out McDuff's often mid-tempo tunes from end to end. In the '60s, McDuff did his thing for nearly every major record label, with a string of tough guitarists including Grant Green, Kenny Burrell, and most notably, a young George Benson. He put out a string of consistent records with names and song titles somewhat lacking in subtlety (Whap!, Smut, Crash!, The Honeydripper, The Vibrator), but reflecting the character of both the organist and his music — sly, joshing, unpretentious, and rife with catchy melodies and gritty blues.

Of late, McDuff is as busy and as happy as ever. Now into his 70s, he's put out a fresh string of albums for Concord that feature old pals from the '60s, like Benson, and new recruits and acolytes, such as guitarist Mark Whitfield and organist Joey DeFrancesco. With nearly 300 songs under his belt, he gets a steady income from the royalties and only tours when he feels like it — often sharing blowout gigs with other '60s B-3 giants, like Jimmy McGriff and Jimmy Smith.

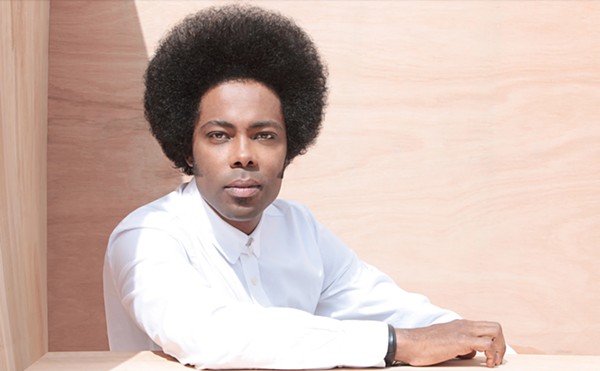

On a summer afternoon, sitting out on the terrace of the Minneapolis home he shares with his wife, McDuff can't decide what he's more excited about: his recent concert appearance with Doc Severinsen and the Minneapolis Symphony, or the fact that he had to walk only twelve blocks from his home to make the gig. The man sounds like he's never had a tense moment in his life.

"I was coming out here [Minneapolis] to play two or three times a year, and then I met a lady," he said. "You know the rest of the story from there. I still play New York, you know. Whenever I go, they say, "McDuff, don't you miss New York?' I say, "Every chance I get.'"

McDuff grew up in Champaign, Illinois, so it isn't surprising that his inner metronome beats with an easier, Midwestern pace. What is surprising is how he eventually ended up on the organ. Hearing that McDuff grew up in a religious family, with a preacher for his adopted father and a pump organ against the living room wall, it's tempting to just fill in the rest of the story: McDuff + church = a musical education and lifelong influence. Nope, says McDuff. He couldn't play boogie-woogie on it because his parents were too strict, and he never did learn church music.

McDuff had to sneak around the neighborhood, playing boogie-woogie where he could. His musical life began properly and publicly only after he met his biological father, a restaurateur who catered to the University of Illinois students, with gambling in the basement and whiskey served in cups and saucers to fool the local police. McDuff's father bought him his first instrument, a bass guitar.

Before long, McDuff moved to Chicago, playing support to Windy City saxman Johnny Griffin. But Griffin's lightning-fast tempos didn't agree with the mellow, easy McDuff, who switched to piano and set his own tempos. "They played too fast, man. Dum, dum, dum, dum, dum," he says, imitating his breakneck walking basslines. "All night."

Heading his own group, a quartet, McDuff kept a regular gig at a Chicago club. But the club owner couldn't afford to play all four musicians. He figured that, if McDuff could play organ and supply the walking bass with the foot pedals, they could drop the bassist. So one night, he approached McDuff, who had never played organ in his life. ""You can have the gig if you can play organ,' he said. So I said, "Yeah, I can play it.' So guess what? When I got to the gig that night, I had to ask the barmaid, "How do you turn it on?' I know she must have thought, "My god, what kind of guy is this?'"

Though it took him a while, McDuff settled in to learning the organ, getting the basslines moving and making the instrument swing. Then he heard Jimmy Smith play one night and found in him the model he would follow for the rest of his career. "I could not believe it," McDuff says. "I'd never heard anything like that in my life."

McDuff has kept a following and sold records all throughout his career — even during the '70s, when most jazz musicians who weren't wearing space-suits or buying wah-wah pedals had a hard time making it. McDuff attributes his success to a populist approach — music regular working joes can appreciate.

"Oh man, let me tell you, it was kicking then," McDuff says. "I've always had a good band. I play a lot of blues — everyone likes the blues, [and] that's what I play a lot. I was lucky, I guess. When I made a record, I had in mind that I didn't make it for the musicians . . . Man, I play for the people — 'cause that sells a lot of records."