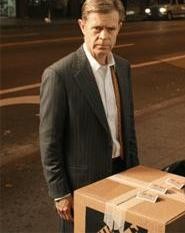

The titular hero (played by William H. Macy) is a nondescript businessman who impulsively gets a doomy Tarot reading on the street and then essentially drops out of his life and marriage (to Mrs. Mamet, Rebecca Pidgeon, who has one small scene and cha-chings it good). From there, Edmond enters the free-for-all night world of masculine indulgence, but with too little money in his pocket and too little experience. His confrontations are predictable, but filled with texture, taking place in several familiar Mamet locales: strip club, bar, whorehouse, one-night-stand flat, pawn shop, back alley.

The guest list is a roster of Chicago theater vets, Mamet alumni, and apparent fans, including Joe Mantegna (as a philosophical bigot), George Wendt (a knife dealer), Julia Stiles (a luckless waitress), Debi Mazar (a bordello clerk), Lionel Mark Smith (a wallet-snatcher -- and a producer on the film), Mena Suvari (a masseuse-whore), Denise Richards (a B-girl), etc. Director Stuart Gordon himself, though more famous for his outrageous Lovecraft adaptations from the mid-'80s, is a longtime Mamet toiler with Chicago's Organic Theater. Still, his enlistment to transform this rabid rant of a playlet into a feature seems peculiar (despite the hammy cutaways to Tarot portents) until we reach halftime, when the scenario goes freaky crimson with stage blood and exploding psychosis.

Writing the screenplay, Mamet hasn't made much effort to update the material (there's even a three-card monte game). A cell phone and/or debit card, certainly standard life equipment for white-collar workers, would've scotched the protagonist's troubles early on. In fact, the political incorrectness that might've seemed so vicious 23 years ago ("nigger," "coon," "cunt," and so on), hardly attains the assault of most hip-hop today and suggests little more than a drunken old white man barking on the street. Which might fit Mamet's scheme better anyhow; being left in the dust of pop culture just adds to the protagonist's irritations. Macy is a star today precisely because of his somewhat dim-witted, likably inept persona, never quite up to the scenes life will have him play and perpetually on the edge of a meltdown.

Here, his clueless everyschmuck is never less than an entertaining sputter, graduating from dim irritation ("That's too much!" he whines again and again, when he's told how much sex of various kinds will cost) to racist fury and beyond. It's a subtle, mounting bolero, if ludicrous, and even if the crack-up's peak involves an emergence of white-supremacist bloodlust that also seems dated and arbitrary (since most of his problems that we've witnessed have been, ironically, with women). Generally, well-off white Midwesterners have long ago gotten over their concerns about African Americans in urban society; today, immigrants carry that burden.

But Edmond isn't a message piece, but another, lesser chapter in Mamet's war-chant requiem for the American male's lost purpose and sense of self. If you're not on board with the surpassingly eloquent horn-blast the playwright fashioned between 1974's Sexual Perversity in Chicago and 1992's Oleanna, then steer clear. As always, Mamet's dialogue has an enthralling, insistent edge to it (his repetitive use of the word "yes" as a response is the style's attitude in a nutshell: civil yet cold-blooded, frank yet secretive). As the full-length sorta-satire it has become, Edmond is all sizzle and little meat, a tangent act dropped from Glengarry Glen Ross because it was several marks too silly.