Inevitably it brings to mind Ray, the film against which it will be compared and contrasted well into the awards season. In so many ways, they're the same movie -- tales about flawed geniuses who belong on rock and roll's Mount Rushmore, where they could find plenty of time to swap stories of marital infidelity and drug use. Too, both Ray and Walk the Line contain performances by actors struggling not to offer rote impressions of men who are easily parodied. And both were directed by lightweights not in the league of their subject matter.

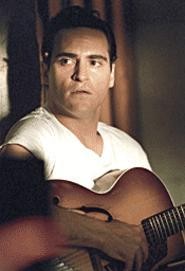

Ray succeeded solely because of its star; Jamie Foxx was Ray Charles, and it was his riveting, star-making performance that allowed Taylor Hackford's dull hagiography to transcend the standard rise-and-fall-and-rise biopic. Walk the Line does not fare so well, because as much as Joaquin Phoenix looks like Cash from a distance (and through squinted eyes), he comes off like a child trying to walk in big-boy boots. It's one thing to try to find the lesser man obscured by enormous myth, but another thing altogether to turn a giant into a whiny, petulant pipsqueak with daddy issues.

Mangold, like Hackford, suffers the fatal flaw of wanting to explain the artist -- to find out what made him tick and what made him ticked off. He begins at the very beginning, in rural Arkansas, and walks the timeline -- crawls it, more accurately, stopping at every significant date in the man's life. There's little J.R. (Ridge Canipe) sharing a cramped bed with big brother Jack (Lucas Till); Jack was Johnny's hero and best friend, the child who dreamed of becoming a minister. But Jack is sliced almost in half by a table saw the very day Johnny skipped off to the fishing hole, which the old man, Ray (Robert Patrick), will never forgive. God, Ray tells Johnny, took the wrong son. (Ray Charles likewise watched his little brother die; it was, Ray informed us, one of the last things he saw.)

Then there's the quick trip to Germany, where Johnny wooed his girl, Vivien (Ginnifer Goodwin), long-distance and began writing songs; then it's off to Sun Records, where Sam Phillips (Dallas Roberts) is recording Elvis Presley (Tyler Hilton, not a bad facsimile) and rebuffing Johnny, who Sam says can't sing country; then it's off to the road, Elvis and Johnny and Jerry Lee Lewis (Waylon Payne) raising hell on a bill with Johnny's slice o' heaven, June Carter (Reese Witherspoon). Then there's the cheatin', the druggin', the singin', the sinnin' -- lather, rinse, repeat till it's the late 1960s, Johnny's touring with June and playing Folsom Prison, and still tryin' to make his daddy proud. And every time something of significance happens, there's the soundtrack cuing another Cash classic, as if to suggest, as all lay biopics do, that moments, not songwriters, write the songs.

The film offers a phony version of history, suggesting that once Cash and Carter were married in 1968, shortly after his Folsom Prison comeback, he was forever clean and sober; hardly. And for all the affection Mangold feels for Cash and Carter, the movie feels oddly dispassionate -- more like a lecturer reading from a required text than someone recounting a story that needed to be told. Phoenix simply doesn't have the weight, the presence, the gravitas of Cash; he looks overwhelmed by the role, as though he's struggling to outrun the ghost over his shoulder. (Country singer Mark Collie offered a far more memorable Cash in the 1999 short film I Still Miss Someone.) Phoenix never disappears into the role the way Foxx did (or as Philip Seymour Hoffman does in Capote, or David Strathairn in Good Night, and Good Luck), never makes us forget we're watching an acolyte repeat the master's words without embodying their meaning. And it doesn't help that Phoenix and Witherspoon sing the songs themselves, rendering theirs the performances of competent karaoke-club entertainers. Phoenix, especially, is no Val Kilmer. Or, for that matter, Jamie Foxx. Or Johnny Cash.