He is not something cute and adorable, like Alfred Hitchcock, the jovial emcee of our collective nightmares. Nor is he just another director eager to make a deal and happy to be working. Nor is he half Andy Warhol, half Andy of Mayberry, or any of the other easy handles that have been stuck on him over the years. It's true he makes entertainingly bizarre comments in a thin, flat, always-polite voice, comments such as: "There is always the surface of something and then something altogether different going on underneath the surface." Or when describing his past: "Growing up, I had a lot of friends. But I loved being alone and looking at insects swarming in the garden." When he talks this way, everyone thinks that he's being ironic in a harmless, homey, neighborly sort of way. But Lynch isn't being ironic. This cannot be stressed enough: He is not being ironic.

And he's definitely not trying to be cute. Perhaps this is a misconception born during the time of Twin Peaks, when a lot of people jumped on the Lynch bandwagon because they thought he was cool and weird without really knowing anything about him beyond this new weird TV show. Or maybe it was all those interviews where he talked about going every day to Bob's Big Boy and drinking all those milk shakes and all that coffee with lots of sugar, which he called "granulated happiness."

Whatever the source of the misconceptions, they persist to this day. And they're not true. David Lynch is a serious filmmaker who gets paid serious money to be one, sometimes by large multinational corporations who ask him for something far-out -- but later lose their nerve and try to renege.

Just ask the French production company CIBY 2000. It signed a contract to back three Lynch movies. It funded the first one, Lost Highway, then finked out on the other two. In U.S. District Court, the judge, in one of the largest judgments ever given to a director for breach of contract, awarded Lynch more than $6.5 million. The judge thought Lynch was a serious person.

When Lynch is not making movies, he is painting or working in his sound and music studio, where he can mix an entire film or record an entire soundtrack. Or he is in his wood shop, making furniture or designing and building an elaborate mousetrap that leaves the captured creature alive and well for release at some place far away.

He is in his painting studio one recent cloudless day, waiting, reluctantly, to talk about his new movie and other matters. The studio is part of a compound of three modern-looking, concrete-and-glass buildings in the Hollywood Hills overlooking the city. At an open end of the studio, four canvases, thick with dark paint, are baking in the sun.

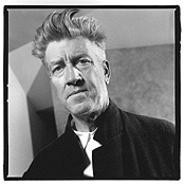

Lynch is wearing his now-familiar uniform: a long-sleeved white cotton shirt buttoned all the way up to the top, a pair of baggy khakis, and scuffed black shoes. Except for the shirt, everything is splattered with paint. At 53, Lynch retains a touch of that clean-cut, all-American boyishness that so amazed the first round of journalists and profile writers who met him in 1978, when his legendary first feature, Eraserhead, began to pop up on the midnight movie circuit, or later, in 1989, during the explosion of publicity set off by Twin Peaks when it first went on the air. Whatever they were expecting, they weren't expecting some fresh-faced Midwestern kid who looked like Jimmy Stewart and who said things like "Let a smile be your umbrella." Recent events, especially a struggle with ABC Television over a prime-time TV project called Mulholland Drive, have left Lynch looking worn out and rougher around the edges than he did during some of those earlier profiles. His once-sandy hair is now a tarnished gray. And though a laugh still comes easily, an expression of lingering worry remains.

For some people, Lynch's new movie, The Straight Story -- a poignant, real-life tale of reconciliation between two brothers, one of whom (Alvin Straight) travels hundreds of miles by tractor to effect a reunion -- isn't just Lynch's most conventional film; it is also his most soulful, accessible movie. For others, though -- some of them Lynch's most rabid fans -- no movie with a G rating is a real David Lynch movie. They want to know what happened. Was his soul stolen away by pod people? How could this master of dark perversion have created this squeaky-clean celebration of Midwestern banality?

The way they see it, Lynch was right the first time, when he said this was a good story, but just not his cup of tea -- that he should stick to doing what he does best, not make patriotic, pro-family-values movies for Michael Eisner at Disney. His job is to say "no!" in thunder, not succumb to smiley-face America.

However, for its supporters, The Straight Story is a David Lynch movie from first frame to last. It feels like a Lynch movie, moves like a Lynch movie, breathes like a Lynch movie. They say that The Straight Story is the most complex, multifaceted, and fully realized work of the director's career.

Lynch took his first stab at filmmaking in 1967, with a creation called Six Men Getting Sick -- a one-of-a-kind, one-minute 16mm film loop. About ten years later, word began to get around about a phenomenal young student at the American Film Institute who had spent five years delivering a paper route on his bike to finance the production of a film called Eraserhead. By the time The Elephant Man came out in 1980, a Lynch movie was something you really didn't want to miss. The Elephant Man received Oscar nominations for Best Direction and Best Original Screenplay.

"I think The Elephant Man was the best thing I could have worked on after Eraserhead," Lynch says. "I was able to find my way into the mainstream and at the same time not compromise. I don't ever want to compromise again the way I did on Dune." Lynch's attempt to bring Frank Herbert's unwieldy sci-fi classic to the screen in 1984 was an unmitigated flop, though a flop shot through with flashes of perverse genius.

"The making of that film was very crazy," Lynch remembers. "We had four crews going at the same time. We had six months shooting principal photography and six months shooting miniatures, models, and special effects." Thinking back, he realizes that the shoot wasn't the problem. "The problem was that I thought I was selling out. I mean, I was selling out. And that was a killer."

That would be the last time he would ever begin a project without first securing final cut. "You see," he says, "you have to be able to feel the freedom when you're making a film, or you're just kidding yourself. If you don't have that, you're just going to die."

Lynch still hasn't seen the American-release version of Dune.

"I never will," he says.

The period after Dune was a bleak one, personally and professionally. In 1986, eager to show the world that Dune had been a fluke, he used his creative freedom to produce the most provocative and original movie of his career: No one had ever seen anything like Blue Velvet. Nor have they since. One of the stars of the film was Isabella Rossellini. Shortly after the release of the picture, she and Lynch moved in together. (This was shortly after his divorce from his second wife, Mary Fisk, the sister of longtime friend Jack Fisk and mother of his teenage son.) According to reports, Lynch was not all that familiar with the Italian-born actress when he was first introduced to her by a mutual friend. "You could be Ingrid Bergman's daughter," he said after staring at her for a few minutes. "You idiot," the friend said. "She is Ingrid Bergman's daughter."

After proving himself on the big screen, Lynch decided to try his hand at the small screen. He created a little tale about a Northwest community that comes unglued when the murdered body of the high school homecoming queen washes ashore, all neatly wrapped in plastic. It was called Twin Peaks, and while it probably did not revolutionize television, it certainly took it to places it had never gone before.

Radical though Twin Peaks was for TV, The Straight Story is the most radical move of David Lynch's career. If Oliver Stone had followed up JFK with a movie version of The Warren Report, it still wouldn't be as bizarre as the turnabout that Lynch has made.

"When David Lynch first approached me to play the part," says Richard Farnsworth, the 80-year-old Canadian actor who gives the performance of a lifetime in the role of Alvin Straight, "I told him that I had been in quite a few movies that had four-letter words in them, but that I had never had to say any of them myself. He assured me that my record would be safe."

Longtime collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, who has composed and conducted most of the music in the director's movies since Blue Velvet, says he was mystified at first. "The whole time I'm reading the script I kept thinking, "When is it gonna become a David Lynch movie?' When I finally realized that he was for real, I was thrilled."

The Straight Story came to Lynch by way of Mary Sweeney, his editor and, since 1994, his partner and companion and mother of his seven-year-old son. Sweeney had heard about Alvin Straight about the same time as her childhood friend John Roach. Straight had made his journey in 1994; two years later he was dead, but not before he'd patched things over with his brother, Lyle (portrayed in the movie by Harry Dean Stanton). Sweeney thought that Alvin Straight's travels might make a good movie, but though she acted quickly, "I found out that the rights had already been snapped up," she says.

Producer Ray Stark had bought the story, hoping to nab Paul Newman to play Alvin, but eventually he backed out of the deal. In 1998, Sweeney optioned the rights from the Straight family. "The story never lost its charm for me," she says.

Sweeney had met Lynch when they worked together on the editing of Blue Velvet in 1985. And while she was tracking down the rights to Alvin's story, she kept telling Lynch what a great movie it would make. But David wasn't necessarily the best director or the first director she thought of. She does admit that, of course, she wanted Lynch to direct it. She would die to have Lynch direct it. She just didn't think Lynch would direct it. "He didn't do anything to encourage me in that direction," she says.

Enter John Roach. Sweeney and Roach have been friends since first grade. Roach has worked primarily in Wisconsin for his own production company, doing television, mostly commercials and industrial films. He also writes for a local paper. "We had just always talked about doing something together," Sweeney says, "and when this story popped up, it just seemed a natural for us to collaborate on it."

The first draft of the screenplay, Roach says, was written in eight days, followed by two weeks of "just throwing stuff back and forth" before Lynch read their script. Rather than think it was just cute or quaint, Lynch liked it.

Though Sweeney and Roach never met face-to-face with Alvin Straight, Roach did speak to him once on the telephone. "He wasn't rude by any means," the first-time screenwriter remembers, "but he was brusque and to the point. He was like a lot of older guys out in the Midwest who will kind of bark at you, just to test you. Once you hold up, they'll give you a wink." Straight eventually became quite eager to have the film made.

For The Straight Story to have become a David Lynch movie required that Lynch recognize that Alvin's story could be -- of all things -- a David Lynch movie. And, of course, once you've seen it that way, once Lynch had transformed it and made it his own, that's the only way it can ever be seen.

In the movie's opening scene -- destined to be a classic -- we hear a thud inside the house. We're outside, focused on an older woman taking a sunbath. Seconds, minutes -- a lot of minutes -- go by. Nothing. Some time later, Alvin is missed at an appointment by friends, who come to see why he is late. When they find him, he's on the kitchen floor of his house, unable to get up. His daughter, Rose, played by Sissy Spacek in a remarkably empathetic performance, is among those who find him. Naturally, he hasn't uttered a sound since he hit the deck. Somebody was bound to come along. Sometime.

It's a perfect David Lynch joke, utterly dependent on timing and pace. For Lynch, pace is everything. It's the life's breath of a movie, its essence. In content, The Straight Story is unlike anything Lynch has ever attempted. And yet, miraculously, it couldn't be more a more perfect fit. It may seem like a departure at first glance, but, on closer inspection, one sees that it isn't.

Which is ironic, since Lynch wasn't looking for a departure. According to the director, it just doesn't work that way. He explains that there are two major factors he considers when trying to decide whether to embark on a project. The first is his personal response to a particular script; whether he feels it has enough emotionally to sustain his interest for the year or two or three it takes to make a film.

The second factor is less concrete. When he talks about it, he talks about something he feels; something that hasn't been verbalized, that perhaps can't be verbalized. He calls it "the air." In all his previous films, the thing that was in "the air" was depravity, darkness, confusion, sickness, rage. Eraserhead was, in his own words, "a dream of dark, troubling things." With Blue Velvet, the effect of "dark, troubling things" was immediate and destabilizing: Watching the movie, you felt short of breath, as if your heart was beating too fast or too slow; that you were going to die. And what more perfect metaphor could there be for America in those final days before the end of the Cold War?

For the next decade, the American movie industry would turn out one anxiety dream after another. Nothing was stable; our security and the safety of our families was largely an illusion or, at best, hung by a string. Movies like The Fugitive set a pattern in which, all of a sudden, a man who has committed no crime of either thought or deed finds himself running for his life, with no one to turn to, accused of a crime he didn't commit.

Lynch's anxiety dreams were the most potent and claustrophobic of all. However, America now is not the same country it was in the late "80s, and The Straight Story signals the mood of a nation in repair, cautiously optimistic and eager to make amends. Alvin Straight is a most uncommon breed of hero -- a hero whose strength is based entirely on his being the most average of men. Once you know the story, the thought of Paul Newman in the part becomes almost ridiculous. Alvin Straight plays no sport and represents no constituency. He hasn't led men into battle or circled the globe in a spaceship, nor does he ride with the support of a corporate sponsor. Alvin represents Alvin. Period. But his approach to life leaves us with the feeling that we would be better off with more people like him in the world. He's not simply a character -- he's a plan of action.

And so, at the end of the American century, this is the reading that Lynch gives us for what's in the air. As Jack Fisk labeled The Straight Story ,"It's a road movie at four miles per hour." It is also a Western, much like King Vidor's Man Without a Star with Kirk Douglas who, near the end of that meditation on the vanishing wilderness, tries to ride his horse across an interstate.

When Lynch is asked if the store of personal darkness that he works out of is greater for him than most people, he answers, modestly, "No more than anyone else. Everyone has their own mix. They have light things, dark things, middle gray -- the whole spectrum. For me, it is the project or the story that determines what part of that spectrum comes out. Everybody has this stuff inside them, these yearnings.

"There are these doors," he says. "You can go through the door for painting or photography or writing. You get directed, and if one door doesn't open, another one will, so that those yearnings can be satisfied. You may not do what you thought you would do, but those yearnings have to be satisfied, or else you become frustrated and you could go crazy. You have to find an outlet, but it's pretty easy, without killing someone."

In terms of violence, Lynch continues: "If you are going to make a film with violence, you want the audience to be able to feel the violence. In the '40s, for example, when films showed violence, only a very few actually did it in such a way that the audience could feel it. Now, people are so used to seeing violence onscreen that you have to push it and push it, almost to an absurd level just so people will feel it. And we've pushed it so far, I think, that there is not much room for us to push it much farther. The pendulum has swung as far as it can in one direction and is starting to swing back the other way."

Many years ago, a much younger David Lynch confessed that he had no intention of getting married or having kids. His goal was to live the almost monastic life of an artist, dedicated wholly and completely to his art. Indeed, some have suggested seriously that Eraserhead, which describes the married life in the most horrifically dark terms imaginable, was a direct response to his recently having become a new father and husband. (His daughter, Jennifer -- herself a filmmaker now -- had just been born. In 1993, she wrote and directed the infamous Boxing Helena.) Since then, he has been married twice, seriously partnered on at least two other occasions, and fathered three children. Again, there has been some speculation that the positive tone of The Straight Story owes its existence to the apparently happy domestic life he's been able to create with Mary Sweeney. And about that he has virtually zero to say.

"It's tricky," Lynch says, closing one eye while exhaling smoke. "And that is all I'm gonna say about that. It's tricky."

He has the same amount of interest in revealing what in life brings him the most pleasure -- what makes him happy.

"You want a new car and you get it, but then the thrill of having that car begins to wear off, or it gets a scratch, or it doesn't handle the bumps the way you wanted it to, then another car comes out that catches your eye. That kind of happiness doesn't last."

As to what does make him happy, that he refuses to answer.