With his band hidden behind a curtain and an intricate light show as his only aid, Jay-Z and his rhymes lived up to his self-created myth, forging a connection to the audience that seemed almost palpable.

Anyone who knows anything about live music would have gladly dropped 40 bucks to see just Jay-Z. But of course, there was much, much more.

Jay's brief moment of triumph was part of a package tour, the dominant format for modern hip-hop concerts. He followed a half-dozen other acts -- oddly chosen stars and one-hit wonders, who did little more than tug their sagging trousers and shimmy to pre-recorded tracks. A few, like Elephant Man, offered almost as many costume changes as songs.

Some would argue that Jay-Z seemed great only because inferior stage performers surrounded him. But I left the arena thinking he suffered by the company he kept, especially after a particular incident.

The biggest ovation of the night didn't occur during Jigga's spellbinding set. It happened, mind you, while the stage was empty and the tour DJ spun chunks of then-current hits like Kelis' "Milkshake" and Twista's "Slow Jamz." The audience rose to greet each new snippet with deafening screams. And they weren't even cheering the DJ -- just records they'd undoubtedly heard hundreds of times before.

That's when I started wondering if hip-hop and concert performance had finally reached the point of irreconcilable differences. Remember, rap originated as a live music on playgrounds in New York City.

Numerous writers, including this one, have weighed in on hip-hop's decline over the past few years. We trot out the same root causes: illegal downloading, offensive lyrics, and the overcommercialization of urban culture.

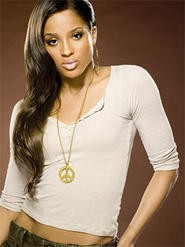

But on the eve of yet another package tour -- Screamfest '07, featuring rappers T.I. and T-Pain, crunk-&-B singer Ciara, and the usual cast of thousands -- it's worth considering how such tours have contributed to hip-hop's current malaise. Not only do they help destroy the live aesthetic once crucial to the music's survival, they imply that hip-hop artists are less artistically relevant than their rock counterparts.

Package tours, of course, have been a pop-music staple for over a century. They serve as an economical way for new acts without much material to get wide exposure. In the golden age of British beat, for example, you could have seen the fledgling Beatles, the Kinks, and the Who, all on the same bill.

The package tour remains a major draw for rock fans, and the music at these concerts suffers from the same law of diminishing returns as their hip-hop counterparts. It's a great value for fans to check out multiple, like-minded bands on the Warped Tour or Ozzfest, but after the first three dozen acts of the day, let's be honest: Does it really matter who's next? All brains possess media saturation points.

Hip-hop differs from rock in one significant respect. Rockers with back catalogs large enough to sustain 90-minute-or-longer shows -- from Dylan to Dashboard Confessional -- usually tour alone. That's not the case with their urban equivalents.

Consider T.I., who just released his fifth album. In the rock world, he'd be headlining shows that would, deservedly or not, suggest his music warrants an hour and a half of your attention. Instead, he's part of Screamfest, which undercuts any argument that he isn't a mere flavor-of-the-month teen idol.

Numerous factors are to blame for this phenomenon. In an age of 80-minute, filler-packed CDs and albums that groan under the weight of accumulated guest stars, music executives have good reason to believe urban audiences prefer quantity to quality. At the same time, hip-hop has long been a singles-based genre; the corresponding belief is that fans want to hear only the hits.

These two seemingly contradictory trends complement one another, creating sprawling concerts with short sets and a dizzying number of performers. They also imply that hip-hop artists, even wildly successful ones like T.I. and Jay-Z, don't deserve the same respect as rock musicians.

An unspoken assumption underlies all this, of course -- that live hip-hop, at least in major venues, isn't much fun to watch anymore. It's hard to argue against this, especially given the death of the DJ as an integral part of the music.

Today's rappers can't connect with their audiences beyond pre-rehearsed "freestyles," stripteases, and simulated coitus. They're not only children of the digital backing track (the bane of all live music for the last 20 years); they've also grown up in the age of hip-hop unreality, where mainstream rap has become a celebration of artificial distances between performers and fans. It's not hard to see how that could have a damaging effect on the live performance.

Personas can make for great theater in performance, of course -- if the MC in question is a great actor, like Jay-Z. But for the young, untrained participant on the average hip-hop package tour, the effect is more like the emperor unclothed before the masses, even before the rapper in question displays his Phat Farm drawers.

Maybe, despite its live-from-the-park origins, hip-hop was always destined to be studio music, and the concert experience has inevitably become irrelevant. There's certainly a long list of pop artists who have faltered live, yet still prospered. But it's hard to imagine that watching more rappers appear artistically nude isn't hurting hip-hop. And in this case, the more, the scarier.