Dub is not a genre! It is a state of mind, with funhouse-mirror eyeballs, a drop floor, a love of the unknown, and the knowledge that if a philosophical truth really does exist, it can be found in the mysterious, malleable ether.

Dub has been the soundtrack of a righteous and adventurous future for as long as it's been around -- writer William Gibson portrayed it as such in his 1984 cyberpunk treatise, Neuromancer (the novel that also helped coin the terms "cyberspace" and "the matrix"). Dub doesn't care too much for fashion; it is forever inside and outside of time.

Of course, in the strict musical sense, dub refers to space-oriented, studio-manipulated reggae and to the method of creation that it has spawned. Since the late '60s, when Jamaican DJs and sound-system operators convinced the island's record labels that the B-sides of singles should carry instrumentals of the A-sides (initially called "versions") in order to better rock parties, dub has been a beautiful musical canvas. When, in the early '70s, genius engineers and producers such as Osbourne "King Tubby" Ruddock, Errol "ET" Thompson, and Lee "Scratch" Perry decided to begin splashing that canvas with the synthetic sounds of a studio mixing board, dub joined abstract expressionism as both a kind of process and a kind of result.

Dub's majesty may not make for a popular 20th-century cultural tale, but it's definitely not new either. What is new is that no matter what musical direction you glance at in 2003, in one form or another, dub glances back. Some of this is just a matter of underground systems growing popular. That the dance-music world has long been indebted to DJs who improvise and refashion records and rhythms using two turntables and a mixer has long been known. As has hip-hop's appropriation of it all, and the addition of an MC -- it simply means hip-hop was paying attention to toaster-fronted sound-systems popular in Kingston. (A fact known by DJ Kool Herc, a Jamaican immigrant who moved to the Bronx and is often credited with sparking hip-hop's flame.)

Yet in 2003, dub's very sound -- not just its setup -- can be heard blasting out of a variety of clubs: Sean Paul, Wayne Wonder, and Timbaland are adding its multicultural bounce to hip-hop's monochromosomes. Thievery Corporation, Kruder & Dorfmeister, and seemingly most of Bristol, England, have brought its smoky sensuality and hood-ornament bass lines to electronica lounges.

Jungle and drum & bass are its hyperkinetic kid siblings. Minimalist techno producers use its thick, undulating bottom to spice up their music's thump. Jam-band kids with diversified post-Dead/Phish aspirations have finally introduced this soundtrack of their early pot-smoking days into their stage shows (some, by incorporating the mixing board that is dub's primary instrument). And indie-alternative kids have treasure-trawled the thrift-store vinyl hope chest of influences and come upon it.

Still, you may ask yourself: Well, how did we get here?

The easiest answer lies in that very punk and post-punk golden era (1974-1981), which indie kids will mine for inspiration until the revolution comes. It is not only a period of time when the first British punks embraced first-generation West Indian immigrants and reggae heads as brothers in anti-establishment arms -- establishment being the House of Lords and the House of Emerson, Lake & Palmer -- it was a time when punk and dub were also the two coolest things around. It was dub's beachhead on music culture and one that it never relinquished.

This collision of worlds is beautifully documented in Wild Dub -- Dread Meets Punk Rocker Downtown, a 13-track compilation of rare dub mined by the label Select Cuts -- wise moves by some of English punk's best-known artists (the Clash, the Slits, PiL, and Billy Idol's Generation X, among others). It is a snapshot of two cultures uniting and the first step in dub's musical proliferation and expansion.

"It was a time when the West Indians taught the English people how to party and helped them claim the right to a nightlife," recalls Vivien Goldman, one of the compilers of the set and its annotator. She's better suited than most to make such fanciful statements. A reporter for a variety of British music magazines in the '70s, a lover of outward-bound black culture (she's also written extensively about free-jazz guru Ornette Coleman and Afrobeat deity Fela Kuti), and a member of the legendary Flying Lizards, Goldman has lived this transformation herself, noting the characters stepping through the door of illegal parties that fueled this mix.

"If you were young and going out at that time, these were the places to go out to [in London]," she says. "No entrance fee and something spontaneously rocking there all night. It was a reggae thing. After-hours joints, parties held in uninhabitable-type places. Very anarchic and very liberating." No wonder, then, that it was a cultural cauldron for the likes of the Clash, Boy George, and future On-U Sound producer Adrian Sherwood.

At a time when punk rock was still scarce, "If you wanted to play the hip records, you played the new Jamaican releases. It was the thing that was happening." And so the music got under the skin of young white musicians, until it became part of their vocabulary -- a vocabulary they continue to pass on.

Dub's no longer strictly for reggae connoisseurs; now everyone on the horizon's got their version. Below are four recent albums that couldn't be more different from one another, all mining this breakthrough idea in modern art -- the shiniest and stankiest Jamaican musical export of them all.

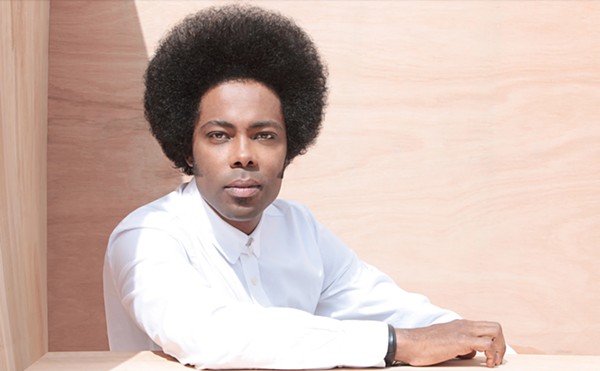

Dub as texture: Pole, Pole (Mute): Stefan Betke is probably the best-known proselytizer of dub's Berlin school, unofficially founded in the early '90s by minimalist techno heads at the Basic Channel label, looking for a deeper bottom than even Detroit could provide. Some might mistake his fourth album's accessible forays into vocals (such as those by underground MC Fat Jon) and dub jazzercises (featuring saxophonist Thomas Haas and bassist August Engkilde) as commercial moves. Though how head music crafted from intestine-rattling low frequencies, ocean-sized open spaces, and snap-crackle-pop riddims can be construed as such is beyond us.

Dub as compositional tool: Out Hud, S.T.R.E.E.T. D.A.D. (Kranky): The one indie-dance dub band to pressure drop if you're citing only one, this Sacramento-turned-Brooklyn quintet learned its dub lessons from On-U and Tortoise records, and its krush grooves from New York, circa '82 (disco meets post-punk) and Detroit, circa '88 (techno, baby). Now their instrumental white-funk flows, while their sensimilla grows -- the percussion tracks percolating with sinewy echoes and the minimalist lines stacked into short, choppy spirals. It's experimental modern music that will also rock a party.

Dub as refabricated memory: Easy Star All-Stars, Dub Side of the Moon (Easy Star): It's the jam kids' and classic rockers' choice -- and not just because it's a dub-wise take on Pink Floyd's Hall of Fame monolith. The All-Stars, who include Antibalas keyboardist Victor Axelrod, approach this remix as Ph.D. students, learned in all classic dubology, but unlikely to rock the boat beyond the initial inspiration. That said, no pothead Floyd fan could possibly escape the gravitational pull of "Great Dub in the Sky" and "Any Dub You Like."

Dub as DNA: Sean Paul, Dutty Rock (VP/Atlantic): This rump-shaker of a dancehall crossover -- which is rocking every decent hip-hop and pop radio station in the country -- isn't stocked with dubs. But the digital designs of such modern dancehall producers as Steely & Cleevie, Troyton, and "Lenky" Marsden are so informed by the language of "rewind, remix" that splitting hairs is pointless. Pick up the 12's of "Gimme the Light" or "Get Busy," and throw on the instrumental versions to hear how dub's finally infiltrated America's Top 40.