Come the first week of June, Dan Ott would be in Michigan, in his new apartment, where most of his belongings and furniture had already been moved, working at his new job.

But on Thursday, May 25, 2006, the Buckeye State was still his home. The 31-year-old and his girlfriend Maryann Ricker were enjoying one of the last nights together in Burton Township in Geauga County. They slept on an air mattress in the living room. Their bulldog, named Mulligan, moped around the mostly empty house scattered with a few boxes.

Ott had spent the past six years becoming something of a rising star in the greenhouse cultivation world. He may have looked like an auto mechanic, but he had a natural ability to coax strong and beautiful plants from the soil. He was a grower, as much a professional title as a magical ability befuddling to anyone who struggles to keep a houseplant alive. Which is how he ended up at Urban Growers in Burton with a working arrangement that allowed him to live rent-free in a small house next door.

It'd served him and Ricker well for three years, but a greenhouse in Michigan had offered him more money to bring his green thumb up north. Ott wanted to run his own operation one day, and this was the logical next step.

Mulligan woke them up earlier than usual the next morning. It was 6:30 a.m. They ignored the pup's pleas and tried to fall back asleep, but were soon startled fully awake by a terrifying image: a masked man in camouflage with a shotgun standing in their house.

In what was a curious moment both then and in retrospect, the assailant asked Ott's name before instructing the couple to lie on their stomachs. He then duct-taped Ott's hands behind his back. When he moved on to Ricker, Ott freed himself from the tape and attacked the intruder, trying to protect the woman he loved. The masked man shot Ott once in the chest and fled.

Ricker called 911 at 6:35 a.m. She talked to Ott while they waited for the ambulance. He responded at first. Then he didn't. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

The murder went unsolved for close to a decade, though it was never a cold case, Geauga County Sheriff Daniel McLelland says. Detectives had leads and rarely did a week go by when they weren't tracking them down. Though no specific details seeped into news reports, the working theory they were chasing was that it had been a murder-for-hire gone wrong.

The gunman had been looking for a man named Dan Ott in Northeast Ohio.

He was just off by some 50 miles and 40 years.

Jason DeLillo didn't think much of the old man who asked about a 2003 Corvette at the Car Connection Superstore in New Castle, Pennsylvania, in 2009. The "older gentleman" was wearing overalls and a surgical mask, the car salesman told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette a year later. It was the summer of H1N1, swine flu was dotting headlines, so the mask didn't strike him as particularly odd.

The old man sat in the car for 10 minutes or so, declined an offer to test drive the car, and left.

The Corvette was gone the next day.

"It's the oddest person you would think would steal a car," DeLillo told the paper.

David Hufstetler, the owner of Hufstetler Auto Sales in North Canton, Ohio, had the same reaction when a Corvette disappeared from his parking lot the same year and authorities came around asking about an old man.

"He's the nicest guy you'd ever want to talk to," Hufstetler told the Akron-Beacon Journal. "It was like dealing with grandpa. Then you find out grandpa is a thief. You think, 'Oh, man, really? That old man?'"

The old man was named Dan Ott.

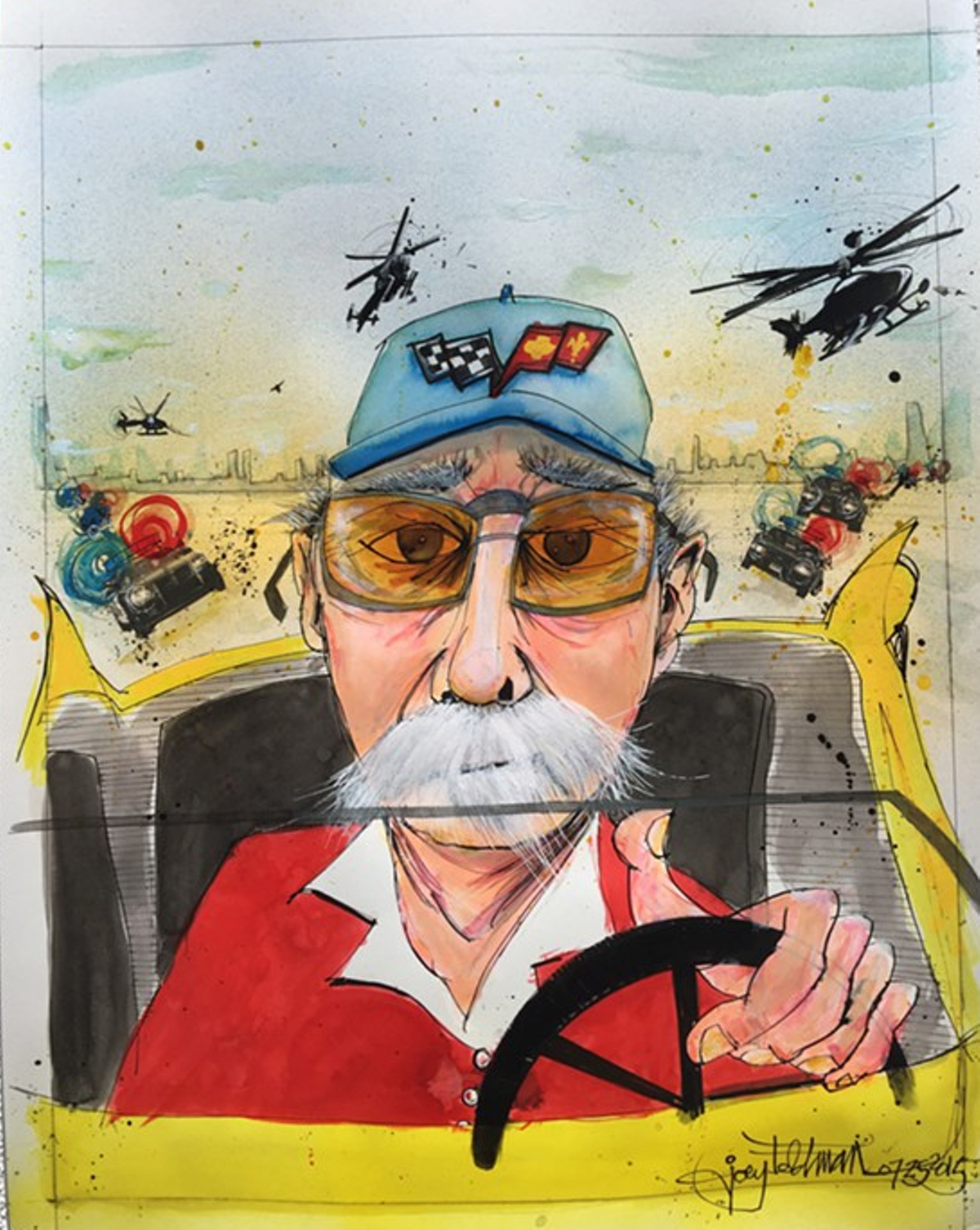

He'd relied on that disarming appearance — his victims feeling unthreatened, if they noticed him and felt anything at all — to do what he did so well. Which was to steal cars. A lot of them. Even into his 70s. Ott was one of the most notorious car thiefs in Northeast Ohio history, but you wouldn't know by looking at him. The old man's looks belied a resume of 1,000 stolen cars, by his estimates. Two stints in federal prison (1998, 2004), four in state (1983, 1987, 1993, and 1995), and untold more in local jails across five decades hadn't convinced him to stop either. A geriatric Gone in 60 Seconds come to life in the guise of an unassuming grandpa.

He kept going at an age when anyone else would be enjoying retirement and senior citizen discounts at the local buffet. The Golden Years for Ott meant hop-scotching across at least a dozen states, fulfilling orders for high-end cars in an auto theft and chop shop ring for $1,200 a pop.

It was just another chapter in a fascinating and complicated life where everything could be stolen and sold, and where all the damage was left in the rearview mirror.

Daniel C. Ott Sr. stole his first car at the age of 13.

He was a paperboy for the Plain Dealer, and when he spotted the 1937 Plymouth coupe with the keys still in it, the decision didn't take long.

"I drove it on my route for two weeks," he says on a brisk afternoon this past February at a downtown Cleveland coffee shop. "I'd park it in a field, but eventually they found it."

It's been 65 years since Ott first got behind the wheel of a car that didn't belong to him. He's 78 now and gets around more than pretty well for a man his age. He shuffles quickly when he walks, like he's performing a reverse moonwalk. Besides some surgery for an aortic aneurysm this spring, he's in fine health.

He's got a dry sense of humor — he wore a Corvette hat and jacket during one interview; he has one that he legally owns too, a red 2002 model. "It's been checked so many times the numbers have worn off," he says — and a damn near encyclopedic recall of his rap sheet, both public and private. He dots conversations with makes and models, each memory tethered to a car, like a kid talking about his favorite baseball cards.

The 1937 Plymouth coupe was first; next was a 1969 Corvette.

Friends, enemies and cops still call him "Red" to this day, a nickname born of once strikingly ginger locks that have long since sprouted white. Five decades ago, in the late '60s and early '70s, he used it for the name of his bar, Red's Tavern (also called Red's Place), on the corner of East 110th and Union Avenue. Ott was slinging drinks at a time and place when Cleveland's criminal underbelly was drinking on the east side, and these were Ott's people.

He'd caught an armed robbery charge by the time he was 22 for robbing $60 from a guy heading to a card game and was introduced into notorious Cleveland mobster Shondor Birn's circle. Ott was a regular on Murray Hill, helping to run counterfeit operations out of the theater. Danny Greene gave him a no-show dock job.

Joining the east-side criminal melting pot were the bikers, who'd set up shop in full force, especially with the arrival of the Hells Angels Cleveland chapter in 1967. They tormented the city with bombings and fights thereafter during some of the bloodiest chapters of the city's history. Bikers found a home at Red's, which didn't go unnoticed. The Ohio Liquor Department recommended his permits be pulled in 1967. Cleveland Councilman Leonard Dacek and others said the bar, "a hangout for motorcyclists and hippies," had adversely affected the "maintenance of public decency, sobriety and good order."

They weren't wrong.

"In 1972 or maybe 1973," says Ott, "there was a guy in the bar in a California Hells Angels vest. He was with a girl. Couple of guys start talking to him, quickly figure out he's not really a Hells Angel. I got a call at the bar from the [Hells Angel] clubhouse asking if I'd call them if he ever came back. He did one Saturday. I called them up. They came down. Beat the guy to death. Made a mess of everything. Broke some tables. She went running down the street. They tried to leave without the body. I told them they had to take care of it."

Legendary Hells Angel Sonny Barger himself came to the bar a few weeks later while he was in town from California, he says. Plunked down $300 on the bar. Thanked Ott for everything he did.

Which is all by way of saying that it's not entirely surprising what happened next, when the 1969 Corvette entered Ott's life.

He bought it from a trio of guys for $2,800, but he and his first wife were driving out to the West Coast soon so he traded in the Corvette for a Cadillac. Ott headed to California on 10-day tags, back when they gave you 10-day tags instead of 30. The dealership was supposed to mail a license plate, but they never did. They sent another 10-day tag instead. They needed the car back. There was a problem.

"The Corvette was stolen. There was a Highway Patrolman at the dealership when I got back and he ran it down for me. I had to give the Cadillac back too," says Ott, who says he didn't know that when he bought it. He'd been involved in other stuff before this — stolen cars, an arrest for receiving stolen property in 1970 — but this, according to Ott, was an entry into something bigger. "I was out the money so I went looking for these guys. I found them at a chop shop at East 71st and Harvard. I went in, saw the garage, saw their operation and what they were doing. I thought from there I could modernize their situation a little better."

He already had connections in the Mansfield area.

"So we rented U-Haul trucks and we started taking their parts and selling them down in Crestline," he says. "I built relationships down there. And then I met some people from Oklahoma. And I met some people from Missouri."

Ott likes to say his business is just like any other business — it's all about word of mouth.

"I bought a house in Columbus since we were spending so much time down there," he says. "We'd go there and do our dastardly deeds in Kentucky, Florida, North Carolina, Alabama, Indiana, Oklahoma, any place really. Word travels. I told one coal miner in Pennsylvania I'd deliver him four Ford F250s at least four times a year. He told a guy in southern Pennsylvania and that guy wanted in too. It's amazing it takes off the way it does."

Within a few years, word of mouth was making Ott $30,000 to $40,000 a month.

Swap out trains for cranes in John Hughes' 1987 film and you'd have the title for a movie about Ott's life.

He didn't just steal cars; he stole just about anything. It didn't matter how unwieldy or impossible. If someone wanted it, he could get it.

He had his pilot's license. Got it after taking classes at Cuyahoga Community College and joining a club at Hopkin's airport. They had three planes: a little Cessna 120, a 150 and 172. Ott learned in the 120, took his pilot's exam in the 150. Bought a mid-'60s Cessna 182G, flew it all over the country, Florida, California. So when the chance came to nab some wings ...

"I only stole four planes," says Ott. "I'd fly wherever the person was selling it, meet them. If you look at the locks on the door, there's a number there. You call the manufacturer and you tell them you need a key, give them some kind of story. They mail it to you. So then I would call the fella and kind of feel him out for when he's not going to be at the airport. I'd fly in, park my plane, jump in his, and leave."

His buyers, he says, usually wanted them to fly to South America for drugs, so if they lost a plane, they lost it. They didn't much care where it came from to begin with.

Heavy construction equipment was a much more regular part of his business, then and more recently. He's taken trailers filled with merchandise and cash from the parking lot of a Columbus horse race, a tow truck from its rotating display platform at a dealership in Central Ohio, camper vans, backhoes, bulldozers ... . At various times, he could have equipped an entire construction business.

"We were taking all kinds of orders for heavy equipment," says Ott. "Caterpillars, backhoes, whatever.

"We had a scam going," he says. "A guy had burglarized a motor home manufacturer in Indiana. He brought back a whole box of certificates of origin. When you manufacture a car or a motor home trailer, they don't give you a title, they give you a certificate of origin. And we had a whole box of them."

Ott got hooked up with a guy in Cumberland, Maryland, who had a car lot. He wasn't doing very good business. Ott had met him through a friend of a friend, he says, in Kentucky. Word of mouth.

"We'd go out and steal new cars in Columbus but we wouldn't have to change the numbers or anything," Ott says. "We put the wheels up on jacks and run some mileage on it. Then take the certificate of origin and make it out for that. We had a girl who'd take the certificate and get a title in a company name. Then we'd take the cars to Maryland and that guy would take them to Butler, Pennsylvania, and sell them at auction."

Like most of his rackets, it worked long enough to make plenty of cash, and by the time anyone was the wiser — the Maryland cars were eventually connected to the Columbus thefts — he'd moved on to another gimmick.

"I've been stopped in stolen cars many times. I used dealer plates though," he says. "I'm not going to say they never reported dealer plates stolen, but they're usually reported lost or misplaced. The plates all have the same number to start and then five or six numbers or letters behind it. When the service department opened, I'd go in the showroom and grab a dealer plate. They have customers out there driving with those plates, so they'd report it misplaced or lost."

In the early days, the physical action of getting into and starting the car was pretty simple: Ott used a tool usually used to pull horseshoes from a pony's feet to grab the passenger side lock from its socket. A Curtis key cutter, the same device your friendly local locksmith uses, was his best friend.

But that only worked for so long. Ott was almost exclusively taking orders for Corvettes in his twilight. The sports car, with its hot rod allure and price tag, was among the most coveted on the road, by fans and thieves alike. While Corvettes have never topped the rankings of most-stolen vehicles in any given year by sheer volume, the ratio of Corvettes manufactured in any given year to the percent of those that are then stolen tells a scary story. In 1984, for instance, Chevy made 51,547 Corvettes. Data from the National Insurance Crime Bureau in the 20 years after shows 8,554 of them have been reported stolen. One in every six.

In 1986, GM introduced VATS (Vehicle Anti Theft System) into the Corvette to stem the tide. The extra layer of security worked so beautifully GM soon installed it in Camaros, Cadillacs and Buicks too.