Let's do a hypothetical. You're in University Circle with some friends from out of town. Maybe you're enjoying a bite in Little Italy or gazing in awe at the world-class collection at the Cleveland Museum of Art. It's been fun. Your friends are thrilled. What about Lake Erie, though? It's close, isn't it? They've never seen a Great Lake before and want to bask in the freshwater wonder before leaving town. Any lakefront parks close by that you can take them to?

You think for a minute and rattle of the options: Mentor Headlands 30 miles to the east; Huntington Beach 20 miles to the west; East Ninth by the Rock Hall, a pier not a park; and Edgewater Park about 10 miles away just west of downtown. Maybe you check Google to make sure you haven't missed anything else — that's it, right? — or maybe some trace of a memory emerges and you say, oh yeah, there's one more option: the Gordon Park area -- with its fishing piers and boat launch ramps -- just three miles north, a nice ride down MLK Jr. Dr. through Rockefeller Park. Seems like the obvious choice, right?

But then you give this some thought for a minute. Is there really anything there? Hardly anyone talks about it. And it's certainly not on any lists of Best Places to Enjoy Lake Erie or Best Places to Take a Visitor published in this mag or elsewhere.

A freeway interchange more than a park, there's certainly no beach. Slivers of sidewalks wedge in the few feet between the six-lane Shoreway and the water, and besides some fishermen, the only action one might catch is a car backing into a parking spot and flashing its lights for an untoward meeting.

This is no show-off-your-city spot. It's more of a reminder of what the city was 30 or 40 years ago, when the lakefront parks were afterthoughts full of filthy diapers and used heroin needles on the ground.

But what this eastside lakefront span once was and could be is now in the thought process of business leaders and city planners. The FirstEnergy Lake Shore power plant – built on this prime lakefront location in 1911 – was torn down earlier this year. And there is talk of taking the 60 acres of land the razed plant yields and turning that into some combination of park, trendy housing, business campus or whatever the moneyed interests and political officials (and maybe community groups) want.

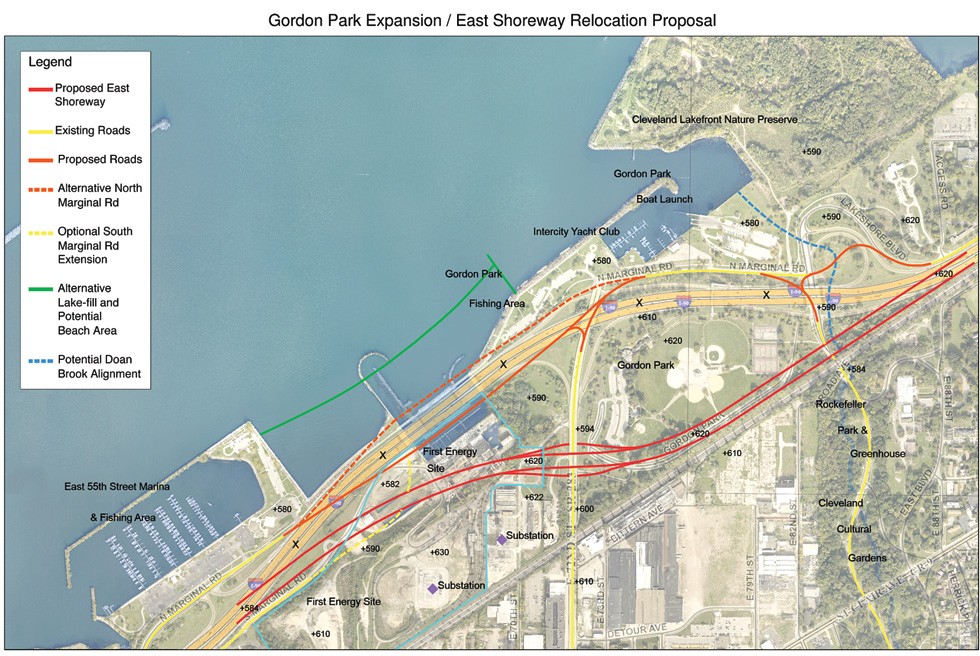

In other words, lots of talk that will likely go on for decades about who cleans up what, why public financing is needed to make neighborhood investment work on this side of town, and how to integrate public parks into the lives of Clevelanders who live in those neighborhoods a few miles away, all in pursuit of making good on long hollow and stalled promises to engage the waterfront. Oh, and the little matter of moving the Shoreway 500 yards south of the water to merge the FirstEnergy expanse with Gordon Park proper, the only way some advocates foresee the possibility of truly creating an Edgewater East.

A whole lot of people look at that lengthy and complex process and figure fixing up this shitty little park simply isn't going to happen. Others see a unique opportunity for Cleveland to plan and follow through on a major civic project, one with a generational impact, that would quite literally change how a large portion of the city's population can engage with one of its prime assets.

"The east side of Cleveland needs their own park, like Edgewater is for the people on the west side," says Dick Clough, executive board chairman of the Green Ribbon Coalition, a waterfront use advocacy group. "The lakefront belongs to the people. We find ways to invest all sorts of money in sport facilities, but we need to have the same urgency when we see opportunities like this.

“The lakefront belongs to the people.We find ways to invest all sorts ofmoney in sport facilities, but we needto have the same urgency whenwe see opportunities like this.”— Dick Clough

tweet this

"Because how we develop this land that is so near so many east side residents, so near to University Circle, and connected to Rockefeller Park, will have implication on this city for this century and beyond," Clough continues. "And just about everyone agrees that moving that freeway so that it doesn't cut the park in two is important. We just need to acknowledge that this is important because of that, and how and who we need to pay for it."

Cleveland city councilman Zack Reed, who is running for mayor against Frank Jackson, agrees. "When people talk about Gordon Park, I usually have to correct them in how they refer to it," he says. "It's not just Gordon Park. It's the neglected Gordon Park. We need to stop neglecting such important places like this in Cleveland.

"It is not a coincidence that the Gordon Park area has been neglected," Reed continues. "The political and business powers in this city firmly believe that property and investment areas that are not downtown or on the west side of the city are really not part of the city."

There is a lot of truth to what Reed says. Because if you look at the history of the Gordon Park area, its rise to prominence came when the white power structure of Cleveland lived in Glenville and Hough. And its slide into deterioration began in earnest when that white power structure moved away as African-Americans moved in after World War II. It is neglect. Nothing else.

***

The Cleveland Public Library has a great map collection. If you want to get some sense of how important now-neglected Gordon Park once was, there are the engineering plans for the park property from the early 1900s. They show bath houses and a big pavilion for festivities and gatherings, with gravel paths and roadways running through, and designs for arbor areas to provide shade for the bathers and their families. In fact, Gordon Park, in its early years, was known as a place where visitors would come at night to escape the heat, to spread their blankets on a hillside overlooking the beach and the let their children run around until they dozed off with their grandparents.

There are three important names on these old plats: Tom L. Johnson, William Stinchcomb, and Charles Schweinfurth. Johnson was the famed "progressive" mayor of the city at the time, and Stinchcomb was the city engineer, who later was responsible for the creation of the "Emerald Necklace" and the Metroparks. Schweinfurth was the city's most well known architect back then, the designer of about 20 mansions on Euclid Avenue's "Millionaire's Row," and also, more notably in history, as the architect who designed the bridges (with their winding staircases) that still arch over MLK Dr. in Rockefeller Park.

“We have an opportunity to change things now that will have an impact for 100 years. We know now thatputting a freeway on the waterfrontis not a good idea.”—Ted Ferringer

tweet this

The reason these men, the best and brightest U.S. urban planners of the time, jumped on this 120-acre piece of property on Lake Erie where the Shoreway's MLK Dr. interchange sits now was that this property was gift to the city to be used as park. When William J. Gordon, who made his fortune in the wholesale grocery and iron ore businesses, died in 1892, he donated that land under the condition that it would forever remain a free, public park.

Ironically, around that very same time, Cleveland industrialist Jacob Perkins gifted a similarly sized property he owned to the city that would eventually become Edgewater Park.

Both became hugely popular in the early 1900s -- the Cleveland Orchestra even played concerts at both the east and westside parks on holidays in the 1920s.

But bad things started happening to Gordon Park. In 1911, the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Co. built its coal-fired power plant just west of Gordon Park. They chose that site because Lake Erie was its front yard (for the water needed to cool the equipment), and behind it were railroad tracks to deliver the coal itself. Because Lake Erie water flows west to east, Gordon Park was downstream from power plants, and its beach quickly became washed with industrial filth.

Then came the 1930s and 1940s, when Cleveland was building the Memorial Shoreway spreading east and west from downtown. It's interesting to see how Edgewater and Gordon parks got treated in this era of transportation expansion. Because of where the power plant was situated, the city decided to put the freeway right on the lakefront, and then have it swing slightly south through the park as it lined up with the freeway planned through Bratenahl.

At Edgewater Park, there was no power plant to avoid, and the railroad tracks were not as close. So the Shoreway ran far enough away from the beach that it remained intact over the years. By contrast, the freeway running next to the lake near Gordon Park effectively killed that beach and sliced the park in two.

Edgewater wasn't immune to various pressures that also caused its decline over the years, but it was maintained, geography-wise. That made it a practical opportunity for a comeback, which is exactly what happened when the Metroparks scooped it up, cleaned it up, and just last year invested $3.3 million in a new 12,000-square-foot beach house for the westside gem.

For Gordon Park, however, there were few such reasons to invest, and the freeway made prospects of a resurgence all but impossible.

"The freeway and the power plant brutalized Gordon Park and the people stopped going there," says Ted Ferringer, the architect who helped design the Edgewater Park beach house. "Edgewater Park would be the same way if the freeway cut through it back then like it did to the east.

"What has happened in Cleveland, especially going out on the east side, is that the property near the lake has been separated into little islands by the railroad tracks and freeways and developmental planning," Ferringer continues. "We have an opportunity to change things now that will have an impact for 100 years. We know now that putting a freeway on the waterfront is not a good idea. So it just makes sense that we should move it now before getting into developing that land better."

***

Everyone contacted for this story who has some knowledge of urban planning and developing and the way people use parks – and the importance these days of parks with water access -- had the same opinion: that moving the freeway makes a lot of sense.

"Without moving the freeway, the [FirstEnergy] property becomes an island, and it makes its ability to be used – and its connection to the neighborhood – much more difficult to accomplish," says local real estate developer Dick Pace.

What Pace and others point out is that in order to do real estate development near the newly-opened power plant property – such as the St. Clair/Superior neighborhood just to the south – the area needs to have access to lakefront park property. Most used the example of Battery Park, just south of Edgewater Park, as an example of how this could work on the east side.

"You could end up with a better development area if the freeway were moved," Pace says. "Not to say that it is a sure deal, that neighborhoods nearby will see some economic benefit, but it is safe to say there is a better chance of that happening if the freeway is moved."

Andrew Brickman, principal owner of Brickhaus Partners, another big real estate development company, says the market is definitely leaning toward condo lofts and apartments that have lakefront access, or at least nearby.

"Lakefront access in Cleveland is going to be at a premium," Brickman says. "Especially if it is close to downtown like this is. It could be a blank canvas to work with, park and development property in the same place."

Where we are in the process now is very early and very vague. The city has hired a New York real estate consultant to present options, and a few of the options they have presented would move the freeway 10 to 20 yards away from where it now abuts the lake. That movement would do little more than make the walkways between the freeway and the water a bit wider than they are now.

No decision will likely be made for years. The reason for that is how complicated this all becomes when the issue of property transfers come into the picture. FirstEnergy still owns the 57-acre site of their demolished plant, and the requirements of the Environmental Protection Agency on who is responsible for cleanup differ depending on how the land would be used. For example, land used for housing has to be cleaned up more than land used for a park.

To make this more complicated, the title transaction of the property from the electric company to the city, a private developer or a foundation could make the new titleholder responsible for cleanup as part of the deal. Prices can vary depending on who takes responsibility for the cleanup.

“The Mayor’s goal is to build uponand better connect the current open space at Gordon Park, the LakefrontMetroparks and the Lake ErieNature Preserve (Dike 14).”—Ed Rybka

tweet this

The difficulty now is that no one knows how much cleanup there might be and how much it will cost. This is more than likely not a "Superfund" cleanup site, but there was a lot of buried coal and chemicals on the property, as well as ashes from burning coal on the property for more than 100 years.

In a statement from the city of Cleveland, Ed Rybka, chief of regional development, left open many possibilities. "The plan presented by the Green Ribbon Coalition is consistent with Mayor Frank G. Jackson's vision and goal of improving citizen access to the lakefront and to the water's edge. The City Planning Department is vetting approaches to create quality green space along the lakefront that connects with the City's neighborhoods and residents.

"The Mayor's goal is to build upon and better connect the current open space at Gordon Park, the Lakefront Metroparks and the Lake Erie Nature Preserve (Dike 14). Part of the City's current lakefront planning process includes the former First Energy facility site. The Green Ribbon Coalition plan is attractive in that a large park space would be created," Rybka continues. "The cost to move the East Shoreway, however, is significant."

(You can read the Green Ribbon Coalition's various proposals here.)As usual, in a city without as many people and as much capital as it once had, the cost of creating a beautiful lakefront park and housing/office development out of an industrial dump site does not come cheaply. Just moving the freeway could cost $75 to $100 million, according to some preliminary estimates. Adding a beach to where the power plants used to suck in water and dump out aquatic sludge might be tens of millions more. Getting street connections under the railroad tracks and relocated freeway would add even more to the cost.

It doesn't stop there. No one really knows how much the developers might need in economic grants to get the process started, or how much the Metroparks might need to spend in conjoining all the properties now separated by the freeway and adding bike paths to do just that.

Oh, and one more thing. Doan Brook, the little stream that runs through Rockefeller Park, goes underground into a culvert when it hits Gordon Park near the freeway crossing. The Green Ribbon Coalition wants to resurrect Doan Brook from down under and allow it to flow freely into the lake above ground near the nature preserve. Like the rest of the parts to this project – saving a park, moving a freeway, cleaning up centuries of detritus, building a beach – no one really knows how much it costs to make a dead stream real again.

***

If you do the math outside of the dollars and cents, you can see more clearly exactly what moving the freeway does in terms of acres. As it currently exists, there are three separate properties, because of the freeway, totaling 129 acres. Only 60 of those are on the lake. Move the freeway south, and you create 160 conjoined acres with lakefront access.

That doesn't even include the 88 acres of the Lakefront Nature Preserve, which would also be connected to the park property.

What the freeway move would mean, in real terms, is that one could stand where the Gordon Park baseball diamonds are now and walk directly to the lake with grass underfoot the whole way. To get there now, one would have to drive their car down East 72nd Street to hit water from the ball diamonds, or walk across the pedestrian bridge, overgrown with weeds and bearing every indication of neglect, over the freeway.

Grace Gallucci is executive director for the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency (NOACA), and she might hold the key to how this is all sorted out. NOACA is the clearinghouse for many transportation projects in five Northeast Ohio counties (Lorain, Geauga, Cuyahoga, Lake, and Medina) and has 45 members from those counties on its board. They approve anything from a bridge redo on Vrooman Road in Lake County to Interstate 480 fixes in Cuyahoga County to a bike path trailhead in Oberlin.

This summer, NOACA approved $15.8 billion worth of transportation projects over the next 23 years. So how would this affect a 1.5-mile freeway move plan that is not on that list?

"It's entirely possible that something like this could be added in to long-range planning as either a tradeoff, or because we are finding we are savings funds because of the cost reduction on another project," Gallucci says.

In other words, maybe NOACA finds that the $278 million to replace decks of the I-480 bridges and construct a third bridge is not needed as much as they thought, and the cost of the project goes down to $200 million. Then NOACA's board could decide to use those funds for something else, like a freeway relocation near a park on Cleveland's east side.

Gallucci said NOACA is going to complete a study, which is expected to be finished in the next month, "to see if there are merits to the idea" of moving the freeway. But even if NOACA finds "merit" to moving the freeway, there are a number of hoops this project would have to jump through to get it done. Among them: the city of Cleveland would have to support the freeway move completely; the five-county NOACA board members would have to approve it, perhaps over their own projects; the Ohio Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration would have to weigh in; and NOACA would have to decide whether an inner-city park project makes more sense to fund with its limited resources than a new freeway interchange out in sprawl land.

"We will be looking at this in the concept of many things, traffic and safety certainly, along with perhaps that one of the main reasons of doing this is to open up this property to park land," Gallucci says. "We don't make policy of land uses but we certainly look at things like this for transportation connection issues. There is truth to the statement that the east side doesn't have really true lakefront access and the transportation design may have something to do with that."

***

As I'm riding my bike north on MLK Dr. through the cultural gardens, I see a seven-foot tall Mother Teresa blessing me from the Albanian garden as I ride by. I think of what this saint once said: "One of the greatest diseases is to be nobody to anybody." Cleveland City Councilman Zack Reed says something similar, that Gordon Park was "neglected to everybody."

The neglect does become very apparent as you move out of Rockefeller Park. Just past mother Teresa, the sidewalk ends. Doan Brook flows under the Schweinfurth arching railroad bridge. There is no car or bike entrance to the baseball fields on your left; in front of you there are no bike lanes any more.

As you move farther north, toward the lake, you find yourself in a mess of freeway entrance and exit ramps, Lakeshore Boulevard twisting through this mess, and no real hint that this is a park at all. More concrete than grass, more parking spaces than places to fish, and certainly no places to even get your toes wet.

It is quite odd in some respect, but these two parks that were connected by design in the early 20th century, and celebrated by the cognoscenti of its time as great urban planning and progressive thinking, are now unconnected and have no relationship to each other.

It gets one thinking about why that is. There are many reasons, of course, but the core reason is very simple: Freeways and cars and railroad tracks and trains and electricity and power plants have always held prominence over people going to a park and taking a swim in Cleveland. Especially if the people who want to dip their toes in the lake don't have much money. At least that's how it's been during most of Cleveland's history.

But then, instead, you maybe think of William A. Stinchcomb, that early 20th century city engineer and architect who created the Emerald Necklace and Metroparks, which we so dearly treasure today. And maybe you heed his words from back in 1929, when great parks for the masses counted, and maybe you see some historical value in moving the freeway from where it is now and tackling something wildly ambitious for the good of the people. "Natural resources are the things which Nature gives us . . . forests, streams, lakes, fresh air -- all of these are great resources and their recreational value to city dwellers far exceeds their commercial value as timber to be cut down and water power to be harnessed by industry."

Stinchcomb signed the paperwork for Gordon Park in 1902. Maybe, a century later, Cleveland will again listen to his wise words.