On April 15, roughly 150 men experiencing homelessness were transferred by shuttle from the Tudor Arms Doubletree Hotel in Cleveland’s University Circle neighborhood to the Ramada Inn in Independence. The men were scheduled to stay there, per the terms of a contract between the hotel and Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry (LMM), until the end of August.

Neither Cuyahoga County’s Office of Homeless Services nor LMM regarded the City of Independence as an optimal location for the unhoused men. Most of them, before Covid, would have been staying at 2100 Lakeside, the largest men’s shelter in the state.

But since March of 2020, the county and its partners have pursued a “hotel hub” strategy to de-congregate shelters. It’s a strategy seen almost universally as a success: by the county, by the nonprofit agencies coordinating logistics, and indeed, by the 10 hotels that have benefitted from $7.5 million in county contracts. The win-win is straightforward. Unhoused men and women have been able to move to environments where they can physically distance and comfortably shelter in place, and area hotels have received critical business during a time of unprecedented precarity.

Strategies of this sort have been adopted across the country, and in Ohio, Gov. Mike DeWine expressly called on cities to participate in them last March.

“We are asking all local communities to include homeless shelters in your planning, so that we can more quickly help support these Ohioans to meet social distancing guidelines,” he said.

In Cuyahoga County, the investment of both public and private resources yielded positive results. One of the pandemic’s few heartening headlines arrived in January, when the Executive Director of the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, Chris Knestrick, told Cleveland City Council that due to the county’s efforts and expanded street outreach, the city had witnessed a 30% decrease in unsheltered homelessness.

Independence nevertheless seemed like an odd choice. It is an office park suburb, 15 minutes by car from downtown Cleveland during non-peak hours, and home to an array of basement-tier regional attractions: the Cavs’ practice facilities, satellite locations of Melt and Slyman’s, the northern terminus of the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad, the tallest building between Cleveland and Akron, Stipe Miocic’s Strong Style MMA gym and a very fancy McDonald’s. It is also home to 7,200 residents, 0.0% of whom, according to 2019 census estimates, are Black.

Like many suburbs in segregated, car-centric Northeast Ohio, Independence is defined less by its racial homogeneity than by its highways. (It’s the one where I-77 meets I-480.) Rockside Road is its main commercial corridor, transecting the community across its northern crest in a relationship not unlike the Ohio Turnpike’s to the State of Ohio. Rockside recalls both Solon and Breezewood, Pennsylvania in the respect that it is both blandly and oppressively commercial, pocked with beige hotels, chain eateries and drab office parks. These are all businesses, it seems needless to specify, and in the aggregate, they employ upwards of 10,000 people. The Rockside Corridor is, in fact, one of only six locations in the region that qualifies as a “job hub.”

As such, the Ramada’s pre-pandemic clientele was overwhelmingly business travelers. Proximity to highways, though, made Independence a popular destination for overflow hospitality during major events. The Republican National Convention, for one.

Not that any of this mattered to the men experiencing homelessness. They arrived in mid-April and found themselves much further away Cleveland and the network of social service providers on which they depend to get back on their feet.

But when the controversy arose, as it did immediately, it wasn’t the unhoused men who complained about their transfer. It wasn’t the unhoused men who instigated the confrontation. It was Independence, and its horrified mayor Gregory Kurtz.

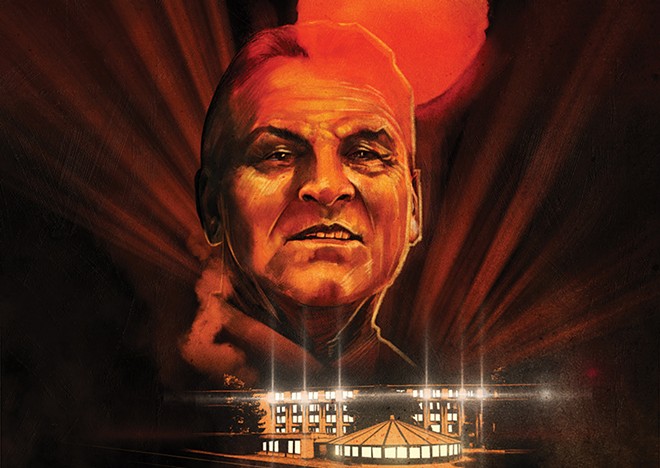

Mr. Kurtz has thrown such a prolonged, screeching tantrum that he appears to have successfully forced LMM to vacate the hotel. It has been one of the vilest and dumbest, not to say most inhumane, local crusades in recent memory. Kurtz has used the leverage of his elected office, the brawn of his police department and the specter of legal action to pressure the county, and by extension LMM, to seek refuge for these unhoused men elsewhere.

When Scene last spoke to a dazed and cautious LMM, they said the contract with the Ramada was technically still in effect through August. More recently, though, the county acknowledged that Kurtz’ intervention bestirred Cuyahoga County Executive Armond Budish into action.

“The Mayor of Independence spoke with Executive Budish to express some concerns about [the Ramada],” a county statement read. “The city advised that Ohio law prohibits any person from staying in a hotel room for more than 30 days. The Executive told the mayor that he would advise HHS staff, who contract with LMM, that Independence intended to enforce the law and requested a transition period to rehouse the existing residents.”

Budish caved, in other words.

“Decades of racist housing policy and stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness have given rise to this scandal,” wrote Cleveland.com’s Leila Atassi, in a blistering column last week. “Budish had an opportunity to subvert the far-reaching effects of that history at a time of unprecedented need in Cuyahoga County. But he failed – caving to political pressure, leaving men unsheltered on the streets and cheapening the county’s promise to end racism wherever we find it.”

It either didn’t occur or didn’t matter to Armond Budish that the law was on the Ramada’s side; didn’t occur or didn’t matter to him that the State Fire Marshal had affirmed, (to Ramada management, to legal counsel and independently to Scene), that the hotel was in compliance with its transient stay license and in no danger of violating state code; didn’t occur or didn’t matter to him that the law in question was not the city of Independence’s to enforce. Neither did it occur nor matter to the gutless Budish that the Ramada is a taxpaying entity in the county he oversees and now may face permanent closure. All that mattered was that Mayor Kurtz wanted the unhoused men out. Yes sir, right away sir.

Elizabeth White, the Ramada’s manager, wrote an open letter last week in response to Kurtz’s announcement that LMM would be severing its contract with the hotel and that the men experiencing homelessness would be departing by the end of the month. Kurtz characterized the decision as LMM’s alone, and said that they, not he, would be best equipped to explain the move.

“This is a bold LIE,” White wrote. “[Kurtz] knows very well why they are leaving. Simply, he is the reason behind it.”

White spoke with Scene before she wrote her letter and said that she was present when Kurtz first met with the hotel’s owner, Sharif Omara, back on April 15.

“Kurtz said in his newsletter that the conversation was ‘unsatisfactory at best,’” White said. “That wasn’t fair. The only thing [Omara] told him was that he wasn’t doing anything illegal. He was dying. He needed the business. And this kind of thing was happening all over the world at a time like this. It’s Covid. Look at New York. And Kurtz said flat out, ‘Not in my city.’”

***

Kurtz’s crusade against the Ramada and the unhoused men staying there began shortly, (that is to say almost imperceptibly), after the contract itself did. On April 16, one day after move-in and the “not in my city” meeting with Omara, Kurtz took to his weekly newsletter to convey his concern to Independence residents. He wrote that due to high vacancy rates caused by the pandemic, some hotels had begun renting rooms to “questionable” organizations.

“The Independence Police have been doing a tremendous job enforcing state and local laws to protect residents,” Kurtz wrote. “I met with my team this morning and have asked them to explore how we can quickly expand and strengthen the City’s nuisance laws and other ordinances related to imminent hazard complaints. I will be meeting with City Council and the Law Director to discuss further legislative and legal actions. Disorderly conduct, loud and destructive parties, and other hotel gatherings where people violate the law put a burden on our safety forces. The city will not tolerate hotel owners who do not operate their businesses responsibly and meet the standards for security and quality.”

Apropos of what now? The Ramada management wondered. This message was delivered not 24 hours after the unhoused men had arrived. There had been no disorderly conduct. There had been no parties. There had been no gatherings of any kind. The entire premise of the hotel hub strategy was decongregation, not congregation, and each room rented by LMM was single occupancy. Moreover, the hotel wouldn’t be open to the public for the duration of the contract term.

“The thing that really gets me is that he called LMM a ‘questionable’ organization” Elizabeth White said. “They’ve been around for 50 years, helping people in the community. What’s the question?”

LMM only arrived at the Ramada because of the NFL Draft. Hotels closer to the heart of Cleveland, and to higher-frequency bus routes, were naturally preferable as decongregation sites. But in the weeks leading up to the Draft, rooms were scarce for the first time in months, and the county wanted to ensure that these would be available for out-of-town travelers. The three-day special event from Apr. 28 – May 1 drew 160,000 fans and hundreds of non-local personnel, shipped in for event setup and security.

Marcella Brown, VP of Development and Communications at Lutheran Metropolitan Ministry, confirmed to Scene that the move to Independence was precipitated in large part by the Draft.

“There was demand for hotel rooms closer to Cleveland, and we never wanted the [hotel hub strategy] to impose upon our community’s ability to generate revenue,” she said. “We are very sensitive to the fact that this project is utilizing public dollars, and we want to be sure that we are being good stewards of those public funds, in partnership with the county.”

The most cost-effective way to decongregate shelters in hotels, Brown said, is to maintain as many residents as possible in a single location. This makes transportation and security more manageable for LMM staff. The Ramada fit the bill. The rooms were available.

Scene asked if LMM had experienced backlash from public officials or residents at other hotel sites in the past year.

“Not to my knowledge,” Brown said. “What I would say is that we are definitely conscious of some of the challenges that the city of Independence is expressing. We get it. But we make every attempt to be as proactive as possible and to communicate, making sure we’re letting them know as much in advance as we can. At times, our need to pivot quickly is based on factors beyond our control. But we make every attempt to reach out and to be in partnership with that community.”

Mayor Kurtz didn’t see it that way. In his April 30 newsletter, he described a meeting with LMM and said he “made it clear that [their] not advising the city about this move in advance was disrespectful to our community, safety forces, businesses, and other visitors.”

He assured residents that the city was “continu[ing] to investigate all legal, jurisdictional, and zoning matters to ensure the hotel owner and LMM are in full compliance.”

As these regular dispatches demonstrate, Kurtz’s crusade was brazenly public. Investigating “all legal, jurisdictional and zoning matters” was another way of referring to the pressure Kurtz and his minions were applying on Ramada management.

Through late April and early May, city personnel in marked cars frequently appeared at the Ramada to take pictures, Elizabeth White told Scene. Members of (she believes) the city’s building department and fire department would show up to scour the property, hunting for minor code violations.

“They’d tell us to fix something. We’d fix it. And then they’d try to find something else,” White said.

The police installed a surveillance camera aimed directly at the hotel’s entrance as well, White said, a tactic she interpreted as pure intimidation.

None of this was kept secret. In Kurtz’s May 7 newsletter, he wrote that “the installation of multiple surveillance cameras in the Rockside Road area is progressing well. These high-tech devices will serve as a powerful tool for our police officers.”

Alongside the explanation of his tactics, though, Kurtz needed to justify the excessive attention.

“The fact that the Ramada situation is temporary does not diminish the immediate and significant burden it puts on our public safety forces and the city budget,” he declared. The reason for this burden? Crime.

On May 11, Kurtz followed through on a threat he’d made the day after the men arrived. The city formally expanded its nuisance ordinances (which penalize property owners for repeat police calls), to include commercial properties in addition to residential ones. There was no illusion about this being anything other than a direct response to the presence of unhoused men at the Ramada.

As local media began covering the story, the narrative pumped by Independence officials – Police Chief Michael Kilbane was the go-to regurgitator of the city line – was that the Ramada guests posed an extraordinary criminal threat.

Stories in Clevleand.com and WKYC portrayed the controversy in Independence as a dispute between two equally valid sides: in one corner, a hotel that cared about the homeless; in the other, a suburban community that cared about safety.

Elizabeth White, the manager, questioned the premise of that coverage in conversations with Scene. She strenuously denied the assertion that the LMM contract was resulting in increased criminal activity. In the WKYC story, Chief Kilbane said that his officers had been called to the Ramada “more than any time in the past.”

“That’s just a lie,” White said.

In fact, there had been far more calls to the police directly before the contract. White said she’d personally called the police on almost a weekly basis because of what she described as local guests throwing hotel parties. She said this was a trend many hotels in the area had experienced after the arrival of federal stimulus checks. The Mayor’s description of “disorderly conduct, loud and destructive parties, and other hotel gatherings where people violate the law,” in his 4/16 newsletter would have been a more accurate description of the situation prior to the LMM contract, not during it.

But the Mayor and police chief seemed intent on characterizing the unhoused guests as criminals.

“There has been an influx of calls since the Ramada began housing the homeless,” the WKYC story reported. “From public intoxication to shoplifting. Even a DOA!”

“That Dead on Arrival thing really upset me,” White said. “They made it seem like it was an overdose or something suspicious. This was literally an old man who died of natural causes. There was nothing suspicious. It could’ve happened anywhere.”

***

“Under Ohio law, the [hotel] owner is allowed to rent a room to an individual for up to 30 days,” Kurtz wrote in his April 30 newsletter. “After that, the hotel room would be considered a “dwelling” which would put the owner in violation of state and City zoning laws.”

(This is the ordinance that Armond Budish credulously accepted as justification when Kurtz appealed to him.)

But according to the State Fire Marshal, the state licensing authority, the Ramada is fully in compliance with its license. No additional action, no special permit, no new variance, is required.

Like most of the hotels in the area, the Ramada has a transient stay license, which allows the hotel to book individuals in rooms for up to 30 days. Kurtz is correct on that point. But as the State Fire Marshal’s Chief of Code Enforcement, Alan Smith, explained to Ramada Management early in the dispute, there’s nothing preventing the hotel from checking out an occupant and immediately checking them into another room to maintain compliance. That sort of thing happens all the time and is perfectly acceptable, as far as the fire marshal is concerned.

On May 10, LMM invited an Independence police representative to the hotel to observe operations. The gesture was in the spirit of transparency and partnership, to assure the city that the hotel was complying with state law and building codes. Despite the personal invitation, an army of Independence officials arrived, a show of force that created a tense and intimidating atmosphere to hotel and LMM staff.

Shaken by the encounter, Ramada ownership and management sought to confirm in writing what the State Fire Marshal had communicated orally weeks prior.

The Code Enforcement official, Alan Smith, wrote to the Ramada’s legal counsel on May 10.

“Please note that the city [of Independence] is acting independently of our office and did not communicate any of today’s events with us,” the message read. “As I explained in reference to the Transient stay license, you cannot have any guests stay longer than 30 days in any single room. Upon checking out occupant, there is no law that states you cannot re-rent a different room to same occupant.”

Joe Savarise, the CEO of the Ohio Hotel and Lodging Association, told Scene that even if the Ramada were in violation of the state law in question – which it is not – Kurtz’s opposition loses sight of the bigger picture.

“You have to remember, this is a global pandemic,” Savarise said. “What this hotel operator did is exactly what Gov. DeWine and homeless experts at the state and national level were calling for. This was to keep everyone safe. I think the response of hotels that answered the call has been commendable.”

Savarise said there should have been an understanding that, during the state of emergency, there would be a temporary use of hotels for different purposes.

“That’s not to say the Ramada violated state law,” he said. “In fact, I still haven’t seen any specific allegation of illegality in Independence. But during the pandemic, hotels have temporarily housed medical professionals, military service members, the homeless population, all as part of the community Covid response. Did you hear anybody complaining when nurses were housed in hotels for more than 30 days?”

The Ramada in Independence was one of 650 hotels statewide, Savarise said, that volunteered their facilities for pandemic-related uses. And he said that his organization had encouraged hotels to do so. The contracts many of them received were a lifeline. Though not highly profitable (the LMM contract was $250,000/month), these dollars helped sustain businesses ravaged by Covid.

Savarise said that Mayor Kurtz’s response, quite apart from the moral question, was illogical on financial grounds. In 2018, hotel lodging taxes generated $1.45 million dollars for the City of Independence. He said that one of the reasons the Ramada made itself available for pandemic contracts was to “fight to keep its doors open” and to return to sustainable levels of operation.

“You don’t get lodging taxes when properties close,” Savarise said. “Far be it for me to make this comment, but talk about shooting yourself in the foot.”

***

For the duration of his crusade, Mayor Kurtz has managed to stay out of the limelight. Other than his weekly newsletters, he has not made media appearances and has confined his advocacy to backroom dealings. While he declined a one-on-one interview with Scene, he did respond to a series of emailed questions, advising us in bold at the top of his message that homelessness was “a complicated and serious public health issue” and that our story required “objectivity and thoroughness.”

In identical comments provided to Leila Atassi, Kurtz said that “unsheltered residents need more than a hotel room. They need medical, mental and substance abuse counseling, job training, and other social services. I urge you to visit the hotel to determine for yourself if these men are receiving the care and support the deserve,” he wrote.

Kurtz confirmed the April 15 meeting with Sharif Omara, the hotel’s owner, and reiterated his bogus interpretation of state law.

“I informed him that the City recognized the Ramada as a Transient hotel, not an extended stay hotel. The City of Independence’s zoning codes prohibit any extended stay hotels. I told Mr. Omara he would need to apply to the City’s Planning Commission to receive a variance. To date, Mr. Omara has not applied for a variance.”

Kurtz also confirmed that he met with County Executive Armond Budish and said he did so to inform the executive “that Mr. Omara (not LMM) was in violation of the City’s zoning code.”

“The County made the decision to ask LMM to transition the current Ramada residents to another location,” he wrote.

In response to a question about why he perceived the unhoused residents as a threat, and why he was compelled to take immediate action to seek their ouster, Kurtz said that he never referred to the unhoused men that way and implored us to stick to the facts.

Sharif Omara’s attorney, Deborah Michelson, provided the following statement in response to our questions:

“It is deeply troubling to us – as we expect it is to decent people everywhere – to read about the apparent lengths to which elected government officials and public servants may have gone to interfere with the property and contract rights of a private citizen, harm his business and reputation, and rid “their” community of vulnerable human beings who need the shelter, kindness, and compassion that my client stepped up to the plate to provide. It appears that these officials, entrusted with public funds supposedly dedicated to the public good, instead may have opened a private back channel and worked out a backroom deal to chase my client’s customers from the place that welcomed them and treated them with respect, humanity, and dignity. The Mayor’s weekly newsletters, which we believe falsely attack and defame the hotel owner and his business (and the Lutheran homeless population, as well), are publicly available, posted on the City’s official website. We find it truly shocking that the City and its lawyers would allow such material to exist on its own website. The harassment these past several months is bringing my client to his knees, forcing him either to capitulate or go out of business. We are disappointed that the Mayor and his team reportedly were able to get County officials to go along with them.”

For Elizabeth White, the most baffling element of Kurtz’ crusade was its gratuitousness. She said that she’s convinced most residents would not have known or cared about the LMM contract if not for the mayor’s newsletters and his public hissy fit. The Ramada is set apart from the residential sections of Independence, tucked away in an office park with limited visibility from Rockside.

“They’re not bothering anybody,” White said. “There’s honestly nowhere for them to go. The only time [residents] might have seen them was if they were walking to the gas station for cigarettes or something.”

So why the horror? Scene wanted to know. Why such vocal opposition from Mayor Kurtz?

“Okay – look. Independence is a predominantly white community, and we’re talking about predominantly Black homeless men. I honestly…” White paused. “I mean I honestly think it’s as simple as that.”

***

Sign up for Scene's weekly newsletters to get the latest on Cleveland news, things to do and places to eat delivered right to your inbox.