Gunther Lahm arrived in the U.S. in 1950 at the end of his parents' protracted escape from Yugoslavia. He was 2 at the time. As refugees, the family sought a new life, one that would grant young Gunther and his seven siblings the democratic spirit of certain human rights and freedoms.

"The right to vote, for us, is a big deal," he says today. That's why, lately, with the presidential election looming, Gunther is pretty fired up.

For the 2014 midterm election, he and his wife, Linda, used absentee ballots to cast their vote. (The couple lives in Franklin County.) Gunther says that everything about the process seemed fine.

This past spring, they got a phone call from an attorney in Cleveland. His name was Subodh Chandra, he said, and he had been mounting a legal battle against Ohio Secretary of State Jon Husted and Attorney General Mike DeWine. Thousands of legitimate votes weren't counted in November 2014, and the Lahms were caught up in that group. Each vote was tossed due to what could be called clerical errors on the part of the voters.

Gunther, an attorney himself, couldn't believe it.

His and his wife's ballots were properly filled out, but they had been placed in the wrong envelopes. (In Ohio, you first must request an absentee ballot. You'll then receive the ballot in the mail, along with a specific envelope to be sent back to the board of elections. You mail the ballot and its envelope back to the board before Election Day.) Gunther's ballot had ended up in Linda's envelope, and vice versa.

Linda had realized this, however — after the envelopes were sealed — and wrote in the necessary changes on each envelope. She and Gunther initialed the edits and dropped their ballots in the mailbox. Done.

Here's the thing: Linda had forgotten to fill in their birthdates.

The Lahms had no idea that this had happened until Chandra came calling this year. "The Franklin County Board of Elections tossed our votes in the trash can, and that got me pretty fired up," Gunther tells Scene.

He says the board of elections never told the couple that their votes hadn't been counted.

By the Nov. 5 deadline, more than 1 million absentee ballots will have been requested in Ohio for use in the Nov. 8 election. That's a sizable portion of the approximately 7.7 million registered voters in Ohio. Husted and his office have actively encouraged the absentee vote. ("So you can vote anywhere with confidence," Husted says in one 30-second ad that's been on airwaves recently.) But the simple mistake that erased the Lahms' votes will surely happen again, along with any number of other ballots for that and other simple errors. Recent court rulings have re-codified the many granular policies that allow county boards of elections to toss absentee ballots in the trash.

After the 2014 mishap, Gunther and Linda say they're skipping the snail-mail absentee thing this year; they'll be voting in person.

***

The ubiquity and scope of the Buckeye State's controversial voting policies are well known.

The Lahms, of course, aren't alone. Take Kenneth Boggs, for example: He voted absentee in 2014 and transposed his birth month with the month in which he filled out the ballot, writing "10" instead of "6" in the birthdate field. Everything else on his ballot was fine, but the board did not count his vote. "I was furious when I found out that my vote was thrown out just because I made a very minor and obvious mistake," he wrote in a signed affidavit.

And there's Elizabeth Coffman: She wrote her current address in the "former address" slot on her provisional ballot form. Her vote did not count in the 2014 midterm election, though she wouldn't learn that until a year and a half later. "I am angry my ballot was thrown out because of this address issue," she wrote.

Keith Dehmann, an active serviceman for the U.S. Air National Guard Reserves, forgot to write in his birthdate on his absentee form in 2014. His vote was canned too. "It made me question whether I should continue doing absentee voting in the future," Dehmann wrote. "I believe my vote should have counted."

This growing problem can be traced most visibly back to a 2010 voting rights consent decree, which itself originates in a 2006 lawsuit filed by a number of advocacy coalitions for Ohio's homeless population. The lawsuit targeted Ohio's stringent voter identification statutes — especially those that were "confusing, vague, and impossible to apply" — and, after years of litigation, the resulting consent decree standardized how boards of elections operated on election day across all 88 Ohio counties. "These voters will not be deprived of their fundamental right to vote because of differing interpretations and applications of the Provisional Ballot Laws by Ohio's 88 Boards of Elections," the decree reads. (The consent decree is in effect through Dec. 31, 2016.)

State lawmakers intervened, however.

Ohio Senate Bills 205 and 216 were enacted in 2014, essentially reversing principal elements of the consent decree and allowing county boards of election to call their own shots and decide how and why certain ballot errors would disqualify a vote. Litigation on that front continues to this day; the bills under scrutiny intersect with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a piece of law in which legislators continue to find gray area.

"[A]ny alleged infringement of the right of citizens to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized," according to a landmark 1964 court ruling, a component of the Voting Rights Act.

As the bills transformed into law, the ACLU of Ohio laid out the case: "One of the most concerning aspects of SB 205 is the addition of the word 'incomplete' in reference to a voter's absentee ballot identification envelope. Giving discretion to a few election officials to define exactly what this word means is likely to result in more ballots not being counted. Additionally, this language is overly broad language and could violate federal law."

Opponents of the new laws draw comparisons to the sort of literacy tests that flourished in earlier periods of American history. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 banned those policies. Husted and the state insist that the laws are meant to "make it easier to vote and harder to cheat."

That latter issue has become a daily topic of discussion, led by Donald Trump's unsupported, egregiously dangerous and roundly debunked claims that the election is rigged. Husted announced last year, for example, after an extensive investigation, his office found that 145 non-residents registered in the state in 2014 (27 actually cast ballots). That's .002 percent of the total voting population. This week during an interview on CNN, Husted, himself a Trump supporter, countered Trump's dubious garbage by saying, "I can reassure Donald Trump, I am in charge of elections in Ohio and they're not going to be rigged. It's bipartisan, it's transparent, and there's no justification for concern about widespread voter fraud."

But many are concerned that a disjointed set of standards across the state could lead to problems with provisional and absentee ballots.

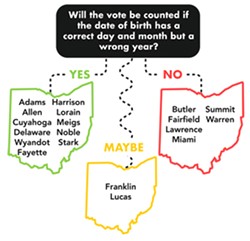

With every county working with a different set of policies, it's difficult to keep track of which T's need to be crossed and which don't. Gunther and Linda Lahm forgot to add their birthdates. In Franklin County, that killed their votes. In Wyandot County, however, that would have been fine. In Cuyahoga County, "maybe," according to documents filed in federal court. And that's just one iteration of the law.

Andrea Margaret, a former Clevelander who's since moved out of state, says that Ohio denied her absentee ballot, "because I got married and changed my name, despite letting me vote in the primary with the same issue." The county's denial of her ballot arrived in the mail on the last day of registration in Ohio.

The idiosyncrasies in Ohio's policies are numerous, and they affect provisional ballots too — a type of ballot issued to a voter at a polling station that is used when a voter's information doesn't jibe with what's in the database. On Election day, if you haven't brought a proper form of ID, you'll be given a provisional ballot. It requires you to fill out all your information by hand. And, like the absentee ballot issue, there are county-by-county differences in how your ballot is deemed to be complete.

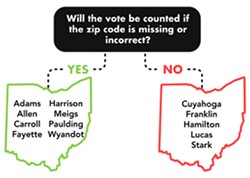

"For example," Chandra says, "if you inadvertently leave your zip code off of your form in Cuyahoga, Franklin, Hamilton, Stark, or Lucas counties, you will be disenfranchised even if the board has no doubt regarding your eligibility, while Meigs and other small counties will count that same vote. How is that remotely fair?"

***

Thing is, the state knows all of that.

Ohio deputy assistant secretary of state Matthew Damschroder, the director of elections in the state, said in March 2016 federal court testimony that, yes, the lack of uniform policies across Ohio's 88 counties troubles him.

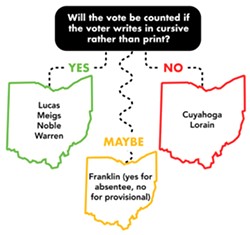

"Would you agree that it is a serious problem if voters in different counties in the state will have their ballot counted or not counted based on the issue of whether they fill their names in cursive or not?" he was asked during a bench trial in federal court. "Yes," Damschroder replied.

"Would you agree, then, that these voters are being subjected to different standards in the application of Senate Bills 205 and 216?"

"Yes."

And that's the origin story of the litigation born in 2006 and still coursing through the federal court system (NEOCH et al. v. Husted et al., for those playing along at home). Reports to the office of the secretary of state show that larger counties — those like Cuyahoga, Franklin and Hamilton, with greater African-American populations — are enforcing the voter identification nuances of SB 205 and SB 206, while smaller and more rural counties are not (as thoroughly). It's a partisan chess game, sure (see also "gerrymandering"), but the implications run deep both on philosophical grounds and in literal terms during an election when the state expects a record number of absentee and provisional ballots to be cast.

That's why, with the election looming, NEOCH and other plaintiffs have continued to fight. In June 2016, judge Algenon Marbley ruled against those idiosyncratic absentee and provisional ballot policies. In short order, though, the state appealed. The case was kicked up to a three-judge panel on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, which offered a multi-pronged ruling that agreed with some of Marbley's ruling ("about 75 percent," Chandra says), but largely left the quirky county-by-county absentee and provisional ballot policies intact — despite those policies directly contradicting the 2010 consent decree that remains in effect.

NEOCH asked for a full hearing on the case. The circuit court denied their motion.

"While we are studying our Supreme Court options," Chandra says, "hopes for affected Ohio voters in this close presidential election may well be lost. Voters may never learn that their ballots were not counted."

NEOCH alleges that many state voting laws are enacted specifically to discriminate against minority populations — mostly black populations and those including wide swaths of homeless and disabled voters in large cities like Cleveland. But that invisible cause is also treated as a defense of the laws. When the state faces up to a struggle to reform voting rights, leaders tend once again to specifically target minority populations: Why cater to those people?

"Government doesn't need to spoon-feed voting materials to voters," State Rep. Mike Dovilla said in 2014. (Here's a quick thought experiment: Did you, a Scene reader and a likely Cuyahoga County voter, know that you couldn't use cursive — or anything resembling cursive — on your absentee or provisional ballot? Blame the government or blame the media, but check your handwriting when you choose to vote. What is "cursive," anyway? The state has no answer.)

During committee hearings for SB 205, State Rep. Matt Huffman asked, "Should we really be making it easier for those people who take the bus after church on Sunday to vote?" Remember that black voters have famously adopted "Souls to the Polls" campaigns in previous elections — bus rides that pick up churchgoers and take them to election locations.

That sort of stuff echoes the words of Doug Preisse, former chair of the Franklin County Republican Party and a member of the county board of elections, who said in 2012, "I really actually feel we shouldn't contort the voting process to accommodate the urban — read African-American — voter turnout machine."

Lines like that — public acknowledgments of how elections are run — get a lot of press. Four years later, the statement is sadly still relevant enough to revisit. As Ohio goes, so goes the nation, according to your preferred talking head. And even if the Buckeye State isn't predicted to be quite the bellwether it's usually been in this election, the enflamed racial and ethnic language bandied about during the campaigns has lent cause to increased scrutiny and voter engagement.

***

Kenneth Payton, a service worker with NEOCH, is driving around the near-westside on Oct. 12, the first day of early voting in Ohio and, by any account, a beautiful fall day on the North Shore. He's picking up registered voters at shelters around Cleveland. This is the first time he's done this for a presidential election. As he sees it, the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless helped register these folks; they probably could use a ride to the polls.

He arrives at St. Malachi on West 25th, a church that offers shelter and a community lunch to those in need. It's about noon and, beneath a warm sun, Abner Rondon explains that this election is more frustrating than most. "With these two candidates, I feel like they're holding a gun to my head, and all I can say is, 'Harambe, I'm coming,'" he says. Rondon is 32, and he says he's not quite ready to vote today. He says he still needs to sleep on his decision a bit.

Payton ends up landing only one voter from this church, a guy named Daniel "Shark" Cruz, a Latino voter from Southern California. Shark has lived in Ohio for a few months; he came here to be a part of Northeast Ohio's budding nonprofit scene. He's a Jill Stein supporter.

"I'm ready," Shark says. "It's time for a third party to take the lead." He says he's glad that Payton caught him before work; it's not always an easy process, juggling the mountain of life responsibilities and getting down to East 30th and Euclid to vote. (Shark is later seen running down Euclid, just barely catching an eastbound bus before it departs.)

As federal district court judge Algenon Marbley summed up the case in June 2016, "Plaintiffs further contend that the challenged laws violate Section 2 of the [Voting Rights Act] because they will have a disproportionate impact on African-American and Latino voters, and that the Ohio legislature in fact intended as much."

Another thing: Eight to 10 percent of the NEOCH homeless population is "absolutely illiterate," according to court filings. And with the known problems associated with filling out an absentee ballot, many volunteers will be in the driver's seat these next few weeks, taking registered voters to the polls. (Poll workers are allowed to help fill out a voter's form if he or she is blind, disabled or illiterate.)

Largely, though, the fight playing out in the courts has two sides: offering Ohioans more or fewer opportunities to vote.

Golden Week, which no longer exists in Ohio, was a window of time at the start of the early-voting period wherein residents could both register to vote and actually vote on the same day and at the same place. It's become a contentious issue over the years, and just this past August the Supreme Court ruled that Ohio's state leaders were within their rights to eliminate Golden Week.

Conversely, another federal court ruling that same month barred North Carolina from implementing certain elements of its voter identification law — its analog to those aforementioned Senate bills in Ohio — that would have mandated the use of government-issued photo ID cards at polling places. The court specifically called out the "racial discrimination" inherent in that law.

***

The state is "making it easier to vote and harder to cheat," Husted says of his work. Repeatedly.

The "harder to cheat" clause is noteworthy, because that implies voter fraud, the bogeyman that paves the path toward voter identification crackdowns.

Again, though, as the state knows, there is at most an almost imperceptible level of "voter fraud" in Ohio elections. Damschroder said as much during his March 2016 testimony: When asked whether the possibility of voter fraud was a justification for the "five fields requirement," he agreed that it was not. That requirement refers to "name, residence address, date of birth, signature, and some form of ID," the sort of thing that tripped up thousands of Ohioans two years ago and that will trip up thousands this year. (On the national front, a Loyola professor tracked and investigated allegations of voter fraud from 2000 to 2014. Thirty-one credible instances were found out of more than 1 billion ballots cast.)

Absent a lawsuit of the magnitude of NEOCH et al. v. Husted et al., there's no guarantee that the issue would have been publicized.

"They had ways to contact us, because obviously we were registered voters," Gunther says of the Franklin County Board of Elections in 2014. "They didn't make any efforts to contact us — never contacted us. That's what really cranked me up. Even if they were going to question this ballot, which is their right to do — but not to contact us, having agreed that that would be done statewide, that got me fired up pretty good.

"America was kind enough to open its doors to us and allow us to come here," he says. "We became proud Americans."

That's why the Lahms and others have become vocal critics of the way Ohio and its 88 counties have been handling elections lately. When Chandra and his law firm came calling, they answered the request for more voices to fuel this discussion. The couple went so far as to say that they'd fly home from their winter home in Florida to testify. It's important to them.

"We should have more polling places," Gunther says. "We should make it easier. We should want everybody in America to vote, and however that turns out is how it turns out."

Absentee ballots are one avenue toward that idea, and registered voters can still request an absentee ballot through Nov. 5. It's a convenient alternative to the sometimes-very-long lines at polling places around the state on election day. Just don't use cursive.