Kate Mulgrew, the actress wife of Tim Hagan, headlined the Cleveland Stonewall Democrats' get-out-the-vote rally at Bounce Night Club. She took no introduction. Instead, with "Copacabana" as her cue, she stepped up to the riser and began to dance. A crowd filled the stage, following her lead. By "Car Wash," even Common Pleas Judge Thomas Pokorny had shed his suit coat and joined the disco parade.

Stonewall Democrats President Patrick Shepherd watched the scene unfold. "When I set this meeting up, I had no idea we'd be doing this," he said, delighted by the spontaneity. "I bet Hope Taft would never do this."

Moments later, a line of politicians -- Hagan, judges Pokorny and Sean Gallagher, Councilman Zach Reed, County Commissioner Peter Lawson Jones -- took turns at the microphone, pledging solidarity with Cleveland's lesbian/gay/bisexual/ transgender community. Not one hedged or equivocated.

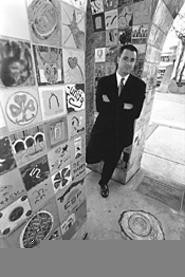

Only recently, such a scene might have been hard to imagine. Gay life in Cleveland has not been measured by its political activism. In a short time, however, Stonewall has emerged as a prized constituency and Shepherd, 32, one of the city's most dynamic operatives. At Bounce, the candidates paid tribute. "Wow, you have no idea what an asset you have in Patrick Shepherd," Gallagher told the crowd. "He's out there. He's working it. He's doing it. He's the man."

Said Lawson Jones: "Pat is tireless, has great energy, and won't be stopped." Hagan all but offered him a job in his unrealized administration.

Shepherd has inspired such confidence by positioning Stonewall not as an antagonistic special interest, but as a political force with capital to spend. Stonewall's mailing list is 1,250 households strong. Volunteers work phone banks. An October fund-raiser raised more than $10,000 for candidates. Earlier this year, Cleveland Heights City Council considered an ordinance to extend benefits to the domestic partners of gay and lesbian employees. Stonewall members packed chambers an hour early on the night of the debate.

"I want to get in the category of the AFL-CIO," Shepherd says. "If you get [Cleveland AFL-CIO Executive Secretary] John Ryan's endorsement, you're going to get money and volunteers, and that's where I want to be."

That Shepherd knows and admires John Ryan speaks to his experience in the political trade. As a Bowling Green student, he took off a semester to work on Bill Clinton's 1992 campaign. He later was executive director of Wood County's Democratic Party. After college, the Wellington native settled into the nonprofit sector, first at the Red Cross and now at the Cleveland Film Society. He resumed a political life when the National Stonewall Democrats formed under Congressman Barney Frank's aegis in 1998.

The Cleveland group first met in 2000, and from the beginning, Shepherd has insisted that it be credible and consistent. Last year, Stonewall decided to wait until after the May primary to make endorsements. When two openly gay candidates for Cleveland City Council failed to finish in the runoff, Shepherd was criticized by some for standing mute. But Stonewall's stated mission is the advancement of equal rights, not gay candidates. Shepherd didn't budge.

The decision appears to have paid off. Councilman Matt Zone, who ultimately won the race in Ward 17, where one of the gay candidates lived, courted Stonewall and became a fast ally. "He's a very disciplined person," Zone says of Shepherd. "If he tells you he's going to do something, you can bank on it."

In an age of shrill debate, Shepherd is a testament to reason and consensus. He doesn't inflame; he informs. Cleveland Heights Councilwoman Nancy Dietrich sponsored the ordinance for domestic-partner benefits, even though Stonewall declined to endorse her in the prior election.

Dietrich today says she understands why Stonewall left her name off its slate of candidates. She walked into the endorsement meeting thinking that, in progressive Cleveland Heights, gays suffered no injustice. She left believing otherwise. Domestic-partner coverage "really seemed to be a wrong that needed to be righted," she says.

The measure passed, 6 to 1.

Dietrich appreciated that Shepherd didn't mistake her lack of awareness for bigotry. "He doesn't see ill will lurking under every stone," she says. It's true. Shepherd is reluctant to label Cleveland Heights Councilman Jimmie Hicks Jr., the lone dissenter on the domestic-partner vote, a homophobe, though Hicks has worked to have the ordinance repealed by referendum. For Shepherd, the enemy is unfamiliarity. "Once a month, I have a meaningful conversation with someone who's never had a meaningful conversation with someone who's gay," he says.

So he stresses visibility. He joined the City Club and Bridge Builders, and he's fine with being known as "the gay guy." Fifteen Stonewallers won seats on the Democratic Central Committee. Initial fears of rejection were put aside when party boss Jimmy Dimora embraced the newcomers, Shepherd says. "He knows we're a formidable constituency."

Besides Dimora opening his big arms and the Cleveland Heights ordinance, Stonewall can look back at a year the cheap-shot "Defense of Marriage Act" died in the Ohio Senate, the mayor of Cleveland first marched in a Gay Pride Parade, and the rainbow flag waved over City Hall.

For now, Stonewall is focused on Cleveland, Cleveland Heights, and Lakewood, the heart of its constituency. "There's a bunch in Parma," Shepherd says, "but I don't know if I'm ready to get involved in Parma politics yet." Spoken like a pro.