In 2011, a pair of scruffy twentysomethings moved into an old apartment above the dry cleaners on Coventry. Nate was from rural Pennsylvania near the West Virginia border. Martez was from Lakeshore, just a couple miles north of Cleveland Heights.

Nate had moved to the city for Tri-C's Recording Arts and Technology program, and through an internship at a local studio started finding rappers for his beats. Martez, meanwhile, was building a local buzz as a rapper while working at Pizzazz near John Carroll.

In the mornings, Nate and his producing partner Matt would pool their money together for Red Bull and a pack of cigarettes. With the $20 or so left at the end of the week, they'd splurge on the ten-cent vinyl bin at Record Revolution across the street. They'd mine the deep cuts and eclectic selections, turning them into samples for beats they'd share with local artists and friends who stopped by their makeshift studio. Oftentimes that'd include a skinny, soft-spoken producer from Mentor named Benny, who made eerie trap beats when he wasn't serving slices at pizzaBOGO up the street, and a Cameroonian transplant named Lorine, who hung out and sung leathery R&B.

Six years later, Martez, or Tezo, as he's better known, has been touring nationally since hopping on a Machine Gun Kelly run in 2012. TrapMoneyBenny, having moved on from the pizza shop, is a Soundcloud pioneer -- his iconic leery, playful production serving as the sonic backdrop for Chief Keef, Lil Yachty, 21 Savage and Playboi Carti. Lorine Chia's doing songs with Wiz Khalifa and The Game, performing on James Corden's Late Late Show, and garnering millions of Spotify streams on her diverse output of funky electro-soul. Nate Fox is now arguably the most important new producer of the past decade, having constructed the sound that propelled Chance the Rapper to the peak of contemporary pop culture.

And six years later, none of them are in Cleveland. One by one they left the city and the brick building next to the Cleveland Heights' Marc's parking lot, where creativity and promise blossomed.

In Cleveland, rap has stumbled, if it ever got a running start at all. The scene is a sprawling, gnarled ecosystem paced by a handful of buzzing upstarts, and churned forward by hundreds of local kids on USB mics. It's propped up by a diverse assortment of cultural and educational institutions, to varying degrees of success. It's a funhouse mirror reflecting some of Cleveland's successes, but mostly its systemic shortcomings. But it doesn't have to be that way.

Fits and Starts

For all intents and purposes, the only rap artists to make it out of Cleveland before 2005 were Bone Thugs-n-Harmony. In 1993, the eastside quintet signed to Eazy-E's Ruthless Records and quickly started churning out hits and collecting Grammy nods. Their signature double time flow is the closest thing Cleveland has had to a signature sound.

Bone Thugs certainly spent a fair amount of time in Cleveland, but they made their money in Los Angeles. And, because of that, their multiplier effect and influence rippled through their record label, not their hometown.

By the mid-2000s the Houston "swang" sound found a second home in Cleveland. Ray Cash blazed a trail that evolved into the Cap Rap era – rappers Fat Al, Chip tha Ripper, Ray Jr., Cory Bapes, and Royalty Camp blended a southern boom with swaggering piano chords and samples into a cohesive sound. While a nascent business management team and record label formed by Rich Paul and LeBron James helped score some major record deals, those, and the attendant momentum, disintegrated.

Cleveland seemed to shoot itself in the foot at every turn. And the two biggest contemporary hip-hop artists to come out of Northeast Ohio recently are atypical examples of success.

Kid Cudi's creative instincts – a genre-bending, melodic, electronic, moody landscape – caught the ear of Kanye West, who co-opted the sound for 808s and Heartbreak, an unquestionable watershed moment for rap music, and Cleveland helped spark that.

If Cudi is our left hook, our right jab is Machine Gun Kelly, another Shakerite whose rat-a-tat flow and punk persona propelled him through the ranks in the city. Kelly spent his early artistic career serving up burrito bowls at Chipotle, working at a Tower City airbrush shop, and unsuccessfully selling weed. He was handing out his mixtape in the high school cafeteria to dubious faces (mine included), and bottom-lining show bills at the Grog Shop for years before beginning to crack through. That came first with a few wins at the Ohio Hip-Hop Awards, later when he caught the ear of Diddy and Bad Boy with a few stand-out mixtapes, and eventually with legendary shows at 2011's SXSW that precipitated his record deal.

This year alone, Kells has had a top five Billboard-charting single and a prominent Rolling Stone profile. He's the face of John Varvatos's Fall collection and is touring Europe. He's Cleveland through and through -- and Cudi still reps the city too -- but they're not your average homegrown hip-hop stars.

While Cudi's initial sound has aged well, his moody electro sing-rap was alien when it first emerged on the scene, for example.

And Cudi and Kelly have also each ventured deeply into rock music -- Cudi has recorded multiple rock albums as WZRD, and Kelly picked up the guitar for a number of tracks on his latest project, bloom. Also, Kelly is white, and, though skilled as a rapper, he'll often cite Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Good Charlotte, or Mötley Crüe as influences before rappers.

It's a bold move for an artist to cross genres, playing with identity and messing with the status quo. It's also one that's hard to emulate, especially for young Cleveland artists who see two atypical examples as the only ones to have emerged from the city in recent memory.

Wallace Settles, the rapper-turned-promoter who books hip-hop acts at the Grog Shop, put it succinctly: "You look at our scene in the last five years and there's about six new artists who've made a national mark and only one where it's been serious: Machine Gun Kelly."

Hurdles

Artists from Miami, Atlanta, Chicago, not to mention New York and L.A., are coming up hand over fist as the internet has opened up the floodgates to consumers. Cleveland artists, meanwhile, can't seem to find a foothold. Much of that has to do with a lack of institutional infrastructure. A few of the resources that exist elsewhere but not in Cleveland include: major record labels or imprints, robust music public relations agencies, publications with national reach that showcase local artists, and marquee festivals, to name just a few.

Jordan Morales, manager of Ezri, a young artist signed to Nas' Mass Appeal Records, paints the picture in terms of what Atlanta has in contrast. "An artist has one record, the whole city gets behind them and they're gone," he says. "Next thing you know they've got a deal or a situation beyond the city limits, or within an Atlanta-based label. In Cleveland, where's that structure? We've got to have a farm system. We've got this baby calf right here, we're nurturing him, and he's gonna be ready to produce some prime steak in about a year. And then as soon as that happens, he gets catapulted through the infrastructures and relationships that have been there."

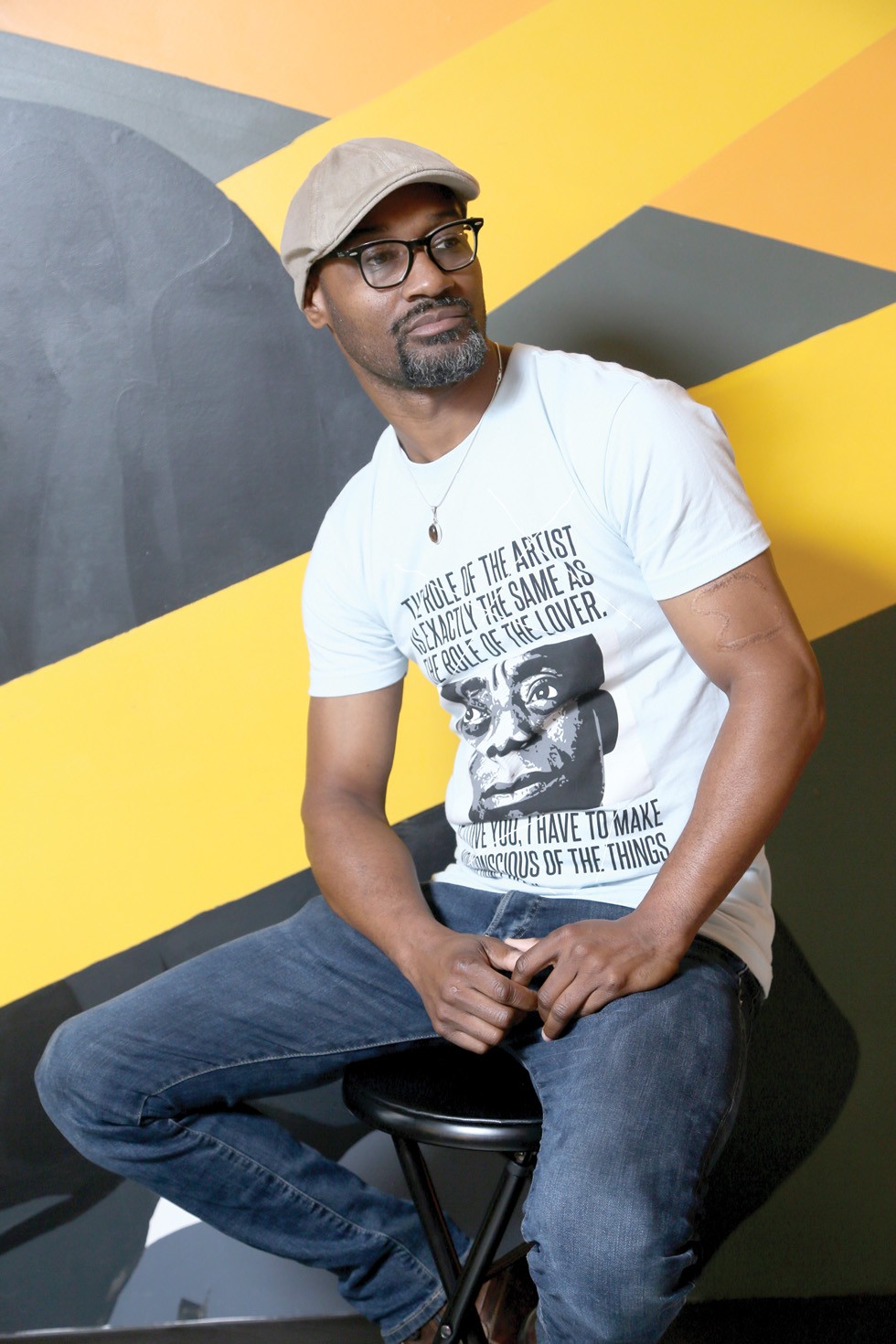

“A lot of our successful artists have left, and they’ve stayed gone, so you don’t have a blueprint for what authenticmentorship can look like.”— Daniel Gray-Kontar

tweet this

Texo elaborates: "The wheels are turning, but nobody's steering the car. Everybody's producing their ass off, rapping their ass off, singing their ass off, but there's no direction. The car might not even be touching the ground."

More than a few also mentioned the lack of accessible mentors who've been through the industry.

"A lot of our successful artists have left, and they've stayed gone," says Daniel Gray-Kontar, a poet, rapper and educator who recently opened the Twelve Literary Arts space in Collinwood. "So you don't have a blueprint for what authentic mentorship can look like. This gets in the way of building, and you need some kind of passing on and continuity."

DJ E-V adds, reflecting on an era before he made his move to L.A.: "I don't think any of us really knew what we were doing. In Atlanta and New York and L.A., there are people who are O.G.s who can step in and help. In Cleveland, there was nobody. Don't get me wrong – Cleveland is the most humble and hardworking place I've been to, period. But with music, everything I need is out [in Los Angeles]. If I need to collab, get something mixed, get something mastered, marketing, networking with publications, interviews – it's all there at my fingertips."

Cudi echoed that in an early interview with Music Connection, explaining his bounce to Brooklyn.

"I always felt trapped in Cleveland," he said. "I'm gonna tell it to you like this, and this might come off crazy, but I was like, "This town ain't ready for me... I wanted to be around people who were like me and there were no people like that in Cleveland. New York is definitely where I shed my skin."

While the natural inclination would be to turn to cities like New York and Los Angeles to find answers and resources, mid-sized cities have been able to develop thriving cores as well. Cash Money nurtured and vaulted New Orleans artists like Juvenile, Big Tymers and Lil Wayne to international stardom before they branched out and signed artists from around the world. Atlanta's LaFace records was instrumental in developing Outkast, TLC, Toni Braxton, and Usher.

Even peer cities like Memphis and Pittsburgh have found success. Yo Gotti's CMG imprint has snatched up every relevant Memphis rapper of the last five years, and Rostrum Records helped develop Pittsburgh artists Mac Miller and Wiz Khalifa from promising teenagers into bona fide stars.

Of course, local labels are a dime a dozen; we mention this handful because they were able to leverage local clout into international success. Most ended up with major label distribution deals, operating under subsidiaries of the big three: Universal, Sony and Warner.

It's worth noting that Dreamlife – the short-lived start-up label fronted by LeBron, Rich Paul and Leonard Brooks – could have been that missing link.

"Dreamlife could've worked because Rich Paul was the guy," Tezo says. "He had dudes performing in front of Jay-Z. He had LeBron in a video. How much bigger can you get?"

Machine Gun Kelly is regularly lauded for maintaining and nurturing his Cleveland roots. He's organized four EST Fests and signed a number of local artists to his imprint, EST 19XX. Maybe one day he becomes that link, but that's down the line, and his signees haven't exactly flourished yet.

Many artists note there are hurdles in the pipeline way before the label stage.

"People have something to say, but they don't have the proper structures or tools, or even someone to tell them, 'Hey, write that down,'" says Morales. Ezri's manager. "And once you're empowered to write it down, not only that, you have a session at 2 p.m. on Tuesday to record it; and after that I'm gonna get it mixed; and after it's mixed you're gonna be able to hear it; and if you like it, we can apply artwork from your one homey who draws for whom we've provided Illustrator even though he's only drawn with pencils and paper up until now. And boom – we've got a single."

The importance of these types of baseline nurturing spaces for young artists can't be overstated. Nate Marshall, the lauded poet, rapper and educator from Chicago, came up through a series of workshops and open mics under the umbrella of the Young Chicago Authors (YCA) organization. Today, Marshall acts as Director of National Programs for YCA, and the organization is gaining cred for its role in nurturing the early creative careers of artists from Chance the Rapper to Noname. The spotlight shines bright on the organization's famous alum, but Marshall thinks its success is simple and can easily replicated.

"A lot of it is just being that gathering place," he says. "Chicago is having a moment, so people want to exceptionalize that moment, but this is just what people do; this is how folks make art.

"The important aspect is people being able to meet each other. Let's say you're rhyming, you're pretty good, and you feel like you're the best in your neighborhood," he continues. "Then you go to this other place where it's like, 'I'm the fifth best person in this room.' But you take that and build with them. It's important to me to convey that what is happening in Chicago is not unique, and not exceptional so that [other cities] don't get to thinking that they can't do it. That space always needs to be created, and it can be a struggle because we're not in a society that's built to value young people or their creative production."

Daniel Gray-Kontar seems to be speaking Marshall's language on both those fronts.

"We do a very poor job of supporting our young in this city," he says. "We do not do a very good job of bringing them to the table and asking them what they need based on their very lived and very real experiences growing up in this city. We do not provide enough access to space and enough access to opportunity based on what they define as opportunity. And because we do a very poor job with that, we lose young people.

"This is about more than just these individual artists; this is about also making Cleveland a better place for everyone to live and work and thrive and to keep our talent here. If we're not asking these key questions and providing support, then we're gonna keep falling into traps. So on the one hand it's very institutional and on the other, it's on us as artists to come together to create the sound, professionalize the sound to make them take notice as well. So this is a two way street."

Underdogs

Two-way streets are two ways for a reason, though. And coming back against the traffic of support is self-evaluation. It's painful to acknowledge maybe you're just not as good as you think you are. Alongside that missing infrastructure is a poisonous thread of entrenched local mentality, an echo of Cleveland's underdog attitude. "We're just as good as X, Y or Z, but no one gives us our credit."

"Why is it that we need validation from The LA Times or The New York Times or The Washington Post to know that we're a dope city?" asks rapper Archie Green, who has recently begun a series of local hip-hop networking and development events alongside his work as a mental health advocate. "We have a very depressed way of looking at ourselves, as though we're not worthy to have a seat at the table with all these other major metropolitan cities."

It's a decades-long cornerstone of Cleveland's scrappy identity, a rallying point to reach out and band together a fragile but proud community. But it's also what causes us to sometimes double down on homegrown mediocrity. That defensiveness, in combination with the internet-bred expectation of instant success in rap, is an insecurity that can end up regressive.

The risk of burning a single bridge by not heaping praise upon another local artist seems to trump much of the constructive criticism that should be fostered. You get labeled a hater, and no one takes a hard look at what could be improved.

Wallace Settles, the Grog Shop talent buyer, buys into that hypothesis. When Peabody's closed in 2013, the Grog Shop became ground zero for live hip-hop in the city, and Settles, a rapper himself who switched careers after encountering one too many promoters smoking weed in their car 20 minutes into a show they were supposed to be organizing, has a front row view of the city's emerging artists. He also doesn't pull punches.

"It boils down to professionalism and quality of music, and lots of our artists lack that here," he says. "A lot of people can't get from 105th and St. Clair to the Grog Shop on time; how you gonna get from 105th and St. Clair to Philly on time? We're not being realistic if people think they can jump out of here and do a national tour. You're not thinking clearly. We can't be skipping steps.

"Everyone wants to move so fast, and no one's taking their time to make quality. You might have to put out three or four albums. You might have to get booed off stage. You might get told no a couple of times. Deal with it. Your feelings are gonna get hurt. You're gonna want to cry. That doesn't mean you quit; that means you keep going. This shit is a fucking process.

"Yes, you're in a small city. Get off your ass. Stop crying. Work harder."

“You might have to put out three or four albums. You might have to get booed off stage. You might get told no a couple of times. Deal with it. Your feelings are gonna get hurt.”— Wallace Settles

tweet this

He's not the only one who thinks the artists could use a kick in the pants.

"I'm always like, 'Man, no one told this person this song was shitty?'" says Alpesh Shah, who co-manages Ripp Flamez. "Maybe there aren't enough bosses, just yes-men."

"It's important to have an educated approach to this music shit," notes Archie Green. "There's too many bedroom rappers; you've got a mic, a Macbook, a MIDI controller, and you think you're an artist, but this is hard fucking work! It's the importance of rehearsal; it's running a small business, learning to communicate with venues and promoters, getting to know gatekeepers as people, not just enablers. "

It can easily (and, in very rare cases, correctly) appear that all it takes is mumbling over a hot loop to become a star – just check out Lil Yachty. The barriers to entry in music creation and distribution have lowered dramatically, though the path to real success remains difficult and often opaque as ever. That dissonance can be difficult to grasp, and when it doesn't go your way, the almost inevitable frustration unfortunately harmonizes with parts of this city's identity.

"Some people say Cleveland's a hater city, but I say Cleveland makes you earn it," says DJ Red-I, one half of FreshProduce. "Your music can't just be good or decent. It's gotta be amazing."

Nate Fox, who spent lots of time in Chicago as he worked on Chance the Rapper's projects, proposes a contrasting approach.

"There's a difference between criticism and being a hater," Fox says. "When I'm in Chicago or New York, I play a beat for someone, they'll say something like, 'Damn, that sample is crazy – I don't know about those 808s though. You can do better.' When I play a beat in Cleveland, someone can not even nod along and be looking at their phone, then just say 'That was tight.' If I'm playing you something that I've done, I'm looking for constructive criticism. It's finding the bar, raising it, pushing each other."

A Way Forward

Given all that, is a robust Cleveland hip-hop pipeline a pipe dream?

Short answer: nope. Just look at some roughly comparable urban areas with similar populations and demographics where it's been done already: Memphis, New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

"Cleveland's had a loser's mentality," says Red-I. "But things have started changing and now there's a whole generation of people are coming up saying, 'We're champions – we have just as much upside, and potential, and right to be here as anybody else.'"

And despite the setbacks and hindrances, more than a handful of artists are making good rap music and carving out paths forward.

Some venture out and get snatched up by surging local labels: 55Bagz signed to Yo Gotti's Memphis-based Collective Music Group, and Kipp Stone was inked with Chicago's Closed Sessions, an indie that's taken some of the city's most innovative artists under its wing, before jetting to sign a indie distribution deal with Empire. MalcUpNext and Q Money flipped Instagram fame into deals in Atlanta. East Cleveland's Doe Boy and his stick-up anthems found a home in Future's Freebandz imprint under Epic.

Another way forward? Placing a strong emphasis on business-savvy, relationship-driven management.

"I've been watching MGK's team since day one," says John Stursa, a Lorain-based blogger who runs Cleveland's pre-eminent hip-hop site, ImFromCleveland.com. "If I had to give advice to another artist, I'd say watch the moves they've made. Look at the pieces he has; he's not doing that by himself. Artists need to buy in and develop those teams."

Paper Paulk has taken that advice almost verbatim. His manager, Derrick Pender, spent years at Bowling Green State University studying business and working with Andre Cisco throwing events, bringing artists from Drake to Wale to Wiz Khalifa to town. More importantly, Andre had been working with MGK since booking him in 2006. By 2011 he was Kelly's road manager.

"Dre is my O.G.. He always understood how to make the most of limited resources – he taught me how to take two and turn it to four," says Pender.

After Paper Paulk dropped his first project in 2012, the pair went down to Austin for SXSW.

"From 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. we were going to meetings and workshops catering to what we needed to learn at the time," Pender remembers, "That first time gave us the exposure to where this could go, and where we had to begin putting a plan in process."

An easy example: A mentoring session with Miles Davis' nephew, of all people, landed them a slot opening for A$AP Rocky on a major stage at SXSW.

The duo used conference and festival gatherings as a proxy for what the city couldn't provide: industry mentorship, access to major media outlets, and national stages. They've been able to flip personal relationships into agency representation, features from A-list artists, and significant coverage from hip-hop media. Over this past summer, Paulk went on a 42-city national tour supporting an artist he'd opened for at 2013's conference: the newly minted XXL Freshman Kap G.

"I rock the stage, then build a person-to-person connection with every fan that talks to me after the show, meet every promoter from every venue, talk to the sound engineers, shake every person's hand." Paulk says.

Ripp Flamez, a native of the Garden Valley neighborhood, has also assembled a strong team around him. Ripp had been developing his signature spacious, smoky, auto-tuned sound in tandem with his brother Ed for years before catching the attention of Alpesh Shah. Shah is a Cleveland native who'd worked as a DJ and manager for years before joining LiveMixtapes, the iconic Cleveland-based rap clearinghouse and media company, and came on as co-manager of Ripp with Ed.

"When he moves, it's like he's signed to a major even though he's not," Shah says. "We have the relationships to facilitate that." LiveMixtapes sifts through thousands of projects, so Shah can suggest potential producers or collaborators for Ripp's consideration, and deliver if he says go.

Shah keeps a place in Los Angeles, and hinted that Ripp and Ed may be heading down to Atlanta to develop further. They're not alone in that instinct to explore what the world has to offer.

"Taking Ezri outside the city and tapping into the culture beyond just the walls of Cleveland early on helped him see beyond the realities of where Cleveland's stake was in music and culture in general," his manager Morales says. "It was crucial."

Ezri became a favorite of the city's tastemakers. As he made his way through MC2 STEM High School, he was being invited to studio sessions hosted by Rich Paul and Ray Jr., and was mentored by Steph Floss. Those connections cascaded into Ezri's eventual Sway in the Morning freestyle, a five-minute tour-de-force that introduced the young rapper to the world. He landed acting roles in The Land and Empire and found a fan in rap legend, Nas, who inked him to his Mass Appeal label. His debut album dropped last week.

Others, like that small Coventry crew, have been more deliberate about leaving the city.

"Just from being close with people like Chip the Ripper and [Fat] Al," Tezo says, referencing two artists whose careers didn't flourish as expected in Cleveland, "I already knew what it was going to take. There's a glass ceiling in this city and you smack it.

"Until that infrastructure builds in Cleveland, you gotta bounce," says Tezo. "To build a real career – book it, bro." He's based in Los Angeles, where he works fairly consistently with TrapMoneyBenny, who agrees.

“I rock the stage, then build aperson-to-person connection with every fan that talks to me after the show, meet every promoter from every venue, talk to the sound engineers, shake everyperson’s hand.” — Paper Paulk

tweet this

"A lot of doors just open up in Los Angeles that you wouldn't get in Cleveland," he reflects. Benny has found unlimited free studio time, vetted lawyers, and the network opened up by his manager's other client, Grammy-winning singer/songwriter James Fauntleroy. "You could just bump into Travis Scott at the studio, or find a random dude who's really good at playing the guitar, ask him to record some shit, chop it up, and it could be the next Rihanna song."

Nate Fox's ascent since leaving has been even more staggering. He produced half of the tracks on Chance the Rapper's breakthrough mixtape, Acid Rap, has writing and production credits on half of the Grammy-grabbing Coloring Book, and even just dropped a song with Paul Simon.

Fox spent five years cutting his teeth in Cleveland, first at Tri-C, then at his studio internship, then in his home studio. But even after he started selling beats, he couldn't see a way out from within the city. "It would've taken a real plan for the future and real money," he says. "We didn't have the knowledge or capability to do what needed to be done to push it to that national level. The pool of ideas of what to do next was very small."

In 2011, his dad came to Cleveland, threw his shit in a truck, and brought him back to Pennsylvania. Nate got a job working construction outside of Philadelphia, and he'd use the money he made to rent a car every weekend and come back to Cleveland or Chicago, where he was developing ties.

At 2012's SXSW, Nate was introduced to Chance the Rapper. "I gave him a beat CD and it had, like, 'Juice,' 'Favorite Song.' After [Chance] got back to Chicago, he recorded it and sent it to me just a few days after. I was like, 'What the fuck is this?'" he remembers. "Then he called me and asked me to do the whole project."

Throughout 2012, Fox spent weekends in Chicago, drove all night Sunday back to his place in Pennsylvania, and start breaking walls with a sledgehammer at 6 o'clock the next morning. "A few days after Acid Rap came out, a guy named Josh Fisher who was interning at Interscope called me like, 'Did you do this shit?' I said yeah, and he was like, 'You need to come the fuck out to L.A. right the fuck now. I got like six meetings for you.' I was like, 'OK,' and I went to L.A. and I'm still here."

We're Still Here

Beyond the success stories of ex-pats or artists patching things together locally, there are tangible efforts being made to bolster the culture at its roots and move past the underdog attitude.

"If you're willing to look with new eyes, you see Cleveland as a great city, a destination, with lots of opportunity," says DJ Red-I as she thinks about the path forward. "We just have to forge it."

Bulkley House, a four-story downtown brownstone on Prospect, opened its doors in 2015 and has become a multidimensional creative space for the professional hip-hop community. With brand new studios, photo suites and podcasting equipment, the space has allowed local talent to simmer, and national acts to pop in while they're in town. In just the last year and a half, Bulkley has hosted studio sessions with artists from Migos to Post Malone. DJ Phatty Banks, one of the producers behind Royalty Camp and a local OG, used the space for sessions on a recent collaborative album, Balance, pairing local emerging artists with established figures in the scene – a perfect embodiment of what Bulkley is all about.

I'm From Cleveland, the only substantial media platform for local hip-hop, is also in a progressive transition. Stursa, the blog's founder, noted that he's in the process of reducing the content he's posting to only highlight the highest quality releases, like local tastemaker-curated Cosign mixtapes.

"I'm trying to make I'm From Cleveland be that Fake Shore Drive for Cleveland," says Stursa, referring to the hugely influential Chicago hip-hop blog whose co-sign is respected nationwide, "highlighting what's on in Cleveland, and pushing it out there, hopefully to a national stage." The recent Complex and XXL features on the Cleveland scene seemed to reflect the groundwork of the site.

The women of FreshProduce are hitting the ground running on a major project combining hip-hop development and entrepreneurship. Coming up through the vibrant community of Tuesday Open Mics at B-Side instilled in them the importance of mentorship and feedback, and they're hoping to provide that for young people in Garden Valley.

"We just got funded for a program called FreshLo, to help develop music and business skills together with some people down in Garden Valley," Playne Jayne says. "We're working with different organizations from around the city and from within the neighborhood to help build entrepreneurial mindsets around hip-hop."

After spending the last year and a half on a planning grant, Red-I and Playne Jayne are helping lead a Kresge Foundation-sponsored two-year program starting in January.

This is huge. Kresge's typical recipients in Cleveland? All the heavy hitters: CPAC, Cleveland Clinic, every community development corporation, Tri-C, Cleveland Public Theatre, even the zoo. And now, an initiative spearheaded by a hip-hop duo.

"This work is the work you have to do. This is the infrastructure building," says Red-I. "Working with groups of people with limited resources and using their creativity and ingenuity to make something beautiful and maybe something people would pay to see. Everyone can't conduct the train, somebody gotta lay the track."

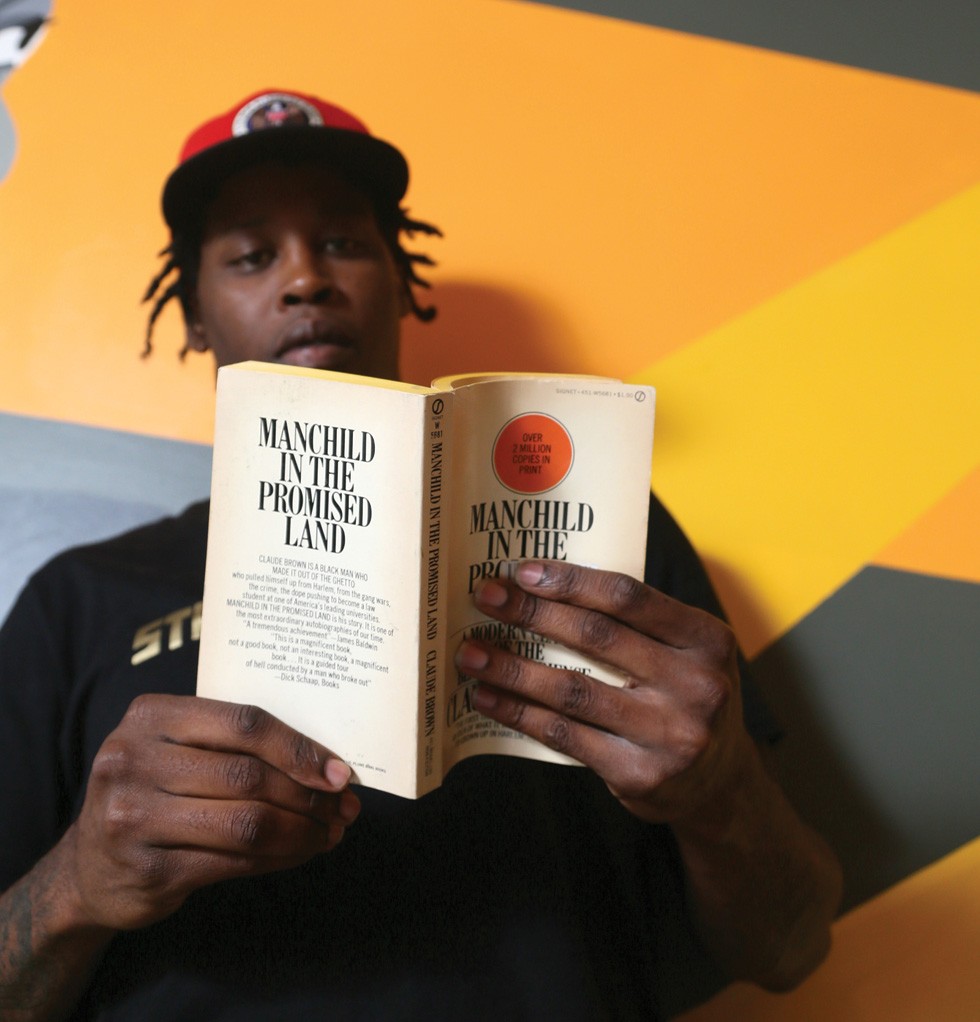

Daniel Gray-Kontar's Twelve Literary Arts space in Collinwood is a strong answer for Chicago's YCA and Nate Marshall's call for a gathering space, and it's growing. Hosting performances, workshops, studio sessions, and informal creative sessions for young artists, it's already knocking down a wall to take over the entire floor in its building.

"Our role is to provide MCs and poets with brick and mortar space for them to feel comfortable doing their thing. It's really minor, but at the same time it's really important. They share their craft with other MCs, or with others who just love hip-hop.

"Our thinking was just creating a teaching space that doesn't feel like a classroom," he continues. "It's literally you just being you and just learning. Like everybody has done before. Somebody like Archie or myself – somebody who has been recording for a long time – almost becomes a mentor. MCs who are not as seasoned at producing high quality tracks get to learn from that mentor even though the mentor isn't teaching in a traditional sense."

“This is the infrastructure building, working with groups of people withlimited resources and using theircreativity and ingenuity to makesomething beautiful and maybesomething people would pay to see.”— Red-I, FreshProduce

tweet this

Archie Green has seen an immediate impact. "Kids were walking the street, and a couple of them walked in just to see what we were doing. We were cyphering, we had beats going, and a couple of these kids got on the mic. The older kid, 14, 15, was like, 'What are y'all doing?' He was detached, but he stuck around, saw and heard what we were doing, and he ended up recording on the mic in our studio space, and by the end of the night, he's helping fold chairs. He cares now. He sees this place in his neighborhood as valuable." Like FreshProduce, Gray-Kontar has managed to tap into funding sources that give these projects sustainability and support.

"A lot of people operate under the premise that there's no money here, but that's a false premise," Gray-Kontar notes, "There's a lot of money here. It's bananas."

For Gray-Kontar, he's leveraged funding from the Cleveland Foundation, which grants almost $90 million annually to community non-profits. Twelve Literary Arts is one of those recipients, and Kontar has managed to find harmony between the foundation's interests and those of the hip-hop community.

"The question for me isn't necessarily how well how do we push back against institutions. It's more, how can I say to those with power, 'These are the needs. Let's create an environment where we meet the larger needs of the city and also meet the needs of the public that we're trying to serve.'

"I'm not the first person that has tried to do that and I'm not the only person trying to do that. I just happen to emerge trying to do some work in Cleveland at a time when Cleveland really needed it, in a neighborhood that is embracing who I was and what I was trying to do. A lot is right place, right time, and just luck."

He might be right. But if Cleveland's rap scene keeps getting more "lucky" breaks, if they champion pioneers seeking to serve young artists and community through hard work, if young rappers start getting the support they need to develop as artists, if the couple of artists who've forged their own path through this Midwestern concrete jungle keep pushing through and giving back, Cleveland could solidify itself as the right place and the right time, no luck about it.