Nothing about its dirt-streaked exterior suggests that the warehouse off London Road could be a repository of good karma. That's only apparent inside. Sofas, beds, dressers, and thousands of other household items, almost all of them donated, sprawl across 15,000 square feet. In this Age of Stratification, the goods offer reassuring proof that the haves actually still give a damn about the have-nots.

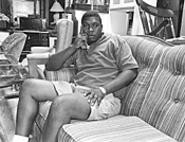

Alas, figuring out which have-nots should receive a dinette set or playpen presents its own kind of burden. Much of that weight rests on the thick shoulders of Alan McDonald, executive director of First Step Alliance, the lone nonprofit furniture bank in Cuyahoga County. He talks with the speed of someone who breathes the cause, words tumbling out in torrents as he describes his work.

Yet as he walks amid stacks of armchairs and end tables, McDonald concedes that his group elicits something less than universal hosannas. First Step has upped the price of its goods and delivery service in the last year, drawing a chorus of criticism from advocates for the poor. They charge that the furniture bank has strayed into for-profit territory -- and morphed into a downscale FurnitureMax.

"You could go to a thrift shop and get things for much less," says Sister Donna Hawk of Transitional Housing for Women. She contends that First Step's prices -- $100 for a sofa, $110 for a crib, $200 for a stove -- put its inventory beyond the grasp of those it ostensibly serves.

Likewise, the group's $75 delivery fee -- up $25 from a few months ago -- has led some nonprofits to send clients to First Step strictly as a last resort. Says Cathleen Alexander of the Domestic Violence Center: "It's the same cost as renting a U-Haul truck just to get a piece of furniture. For some of our women, it's just too much."

In one way, First Step's price hikes differ little from the reaction of other nonprofits to a trickle-down economy that has them dying of thirst. As government guts funding for social services, groups need to raise fees to survive -- leaving fewer people able to afford their programs.

"We know there's a tremendous demand, and we don't want to turn our backs on anyone," McDonald says. "But we serve no one if our doors close."

They've nearly slammed shut countless times. In 2001, First Step served 3,000 customers. Last year, the number plunged to 2,200, with the group sinking more than $65,000 into the red. This year, some 1,000 people languish on the group's waiting list, hoping that other nonprofits or public agencies might rustle up the $150 for a twin bed or $200 for a refrigerator.

The money crunch has forced a seismic shift of the group's customer base. In its early years, First Step primarily catered to the homeless, domestic-abuse victims, and welfare mothers, charging them little or nothing. Now, the disabled and seniors top its list, for a clear-cut reason: They still receive entitlement checks, enabling them to pay for items.

"You can't keep handing out everything gratis and expect to stay in business," says retired accountant Sid Brode, First Step's financial adviser. "You have to generate some income to keep the doors open somewhat to help some people."

But the switch has left the homeless and abuse victims -- already starved for public assistance -- feeling robbed of one of their last crumbs. "We used to be able to pick up things at First Step for free -- we didn't need money," says social worker Toni Johnson, who sits on an advisory panel of the city and county's joint homeless-services office. "But without Libby, they lost their direction."

Libby would be Libby Ellis, who started First Step in the basement of her Solon home in 1992 on the strength of family, friends, and unstinting moxie.

She hewed to a principle that, since the group received donated items, it should give away as much as possible. To cover costs, she bought certain items in bulk, then sold them at a slight markup to public agencies, which still received a better deal than if they'd gone out and purchased the goods themselves. She also created a credit system for nonprofits. When someone donated furniture in a group's name, the nonprofit earned points that later could be cashed in by their clients to obtain whatever they needed for free.

Ellis's spirit, coupled with an initial surge of grant money, sustained the furniture bank through two expansions, first to a storefront and, in 1997, to the warehouse. But as demand deepened and outside funding withered, the nonprofit's board members nudged her toward a fee-based model. She resisted; they heaved her out in 2000.

Today, she's humble enough to admit to past mulishness. But she's also critical of First Step's new approach, saying that what once was a merry band of volunteers has become a bottom-line enterprise obsessed with bean-counting.

"It's been perverted. It's serving the needs of the people running it, not the needs of the people it's supposed to help." Then Ellis, a petite woman with a great heap of curly auburn hair, places a fist over her heart -- a gesture meant for McDonald, whom she hired as operations manager. "Alan's a nice guy. But he doesn't feel it in here."

McDonald, for his part, tosses verbal bouquets toward Ellis, invoking her name every few minutes as he relates what she taught him. Yet he and others counter that First Step confronted an obvious choice: adapt or die.

"Was there a different spirit in 1997? There was," concedes board member Mary Jo Paulett-Toumert. "But you couldn't keep running a business like that. It would have collapsed."

"Business," perhaps, is the operative word. In 2001, First Step collected money from 2 out of every 10 customers. Last year, it jumped to 4 out of 10, yielding $400,000 in revenue. Unlike during Ellis's reign, when customers could walk in off the street, they now must obtain a referral from a nonprofit or public agency -- an attempt to reduce fraud, McDonald says.

As for boosting prices, he insists that the group needed to keep pace with operating costs. He rattles off a list of expenses: the $3,000 monthly rent on the warehouse, the salaries of eight employees, the cost of picking up donated goods, maintenance on three trucks. The group earns between $2 and $8 on items it sells -- a margin that he says has helped push the group "a little bit into the black" so far this year.

Other advocates understand the increases -- to a degree. As Alexander says, "I run a nonprofit, too. If you're facing extinction, raising fees is sometimes the very hard decision you have to make."

But even as prices rise, critics assert, the quality of service plummets, prompting dozens of nonprofits to forgo First Step. Johnson has heard clients complain that they received defective furniture -- or none at all. A spokeswoman for the metropolitan housing authority says First Step has ignored its client referrals. Ex-employees stir murky rumors that workers embezzle funds and cherry-pick the best furniture for their own homes.

Only on that last point does McDonald offer a denial, adding that he's fired a couple of workers for stealing. He pleads guilty to committing honest mistakes, however, saying that the group endures a plight common to nonprofits: too much demand, too few bodies. "We're always scrambling. It's not a perfect science."

He's doing what he can to hammer the dents out of First Step's image, expanding its service into other counties and rebuilding bridges to the homeless. In the past three months, McDonald has arranged for the Salvation Army and Care Alliance, a low-income health-care provider, to send clients his way. Officials for both homeless groups say they're optimistic about the deal -- but, then, they've yet to see an invoice.

"The proof will be in the bill," says the Salvation Army's Mike Green, chuckling. "After that, I might be on the phone yelling at Alan McDonald."