Eugene Johnson is walking north along Strathmore Avenue in East Cleveland, just a stone's throw from his childhood home, a familiar street in one sense but, now, an entirely different universe in another. It's a hot afternoon in September, and families are gathering on front porches as children meander home from school. Those who lived here in the early 1990s surely would have seen Johnson dribbling a basketball down the street and getting some hoops in with his buds after classes — or during, for that matter.

"After what was done to me, I kinda lost that thrill," he says of the game.

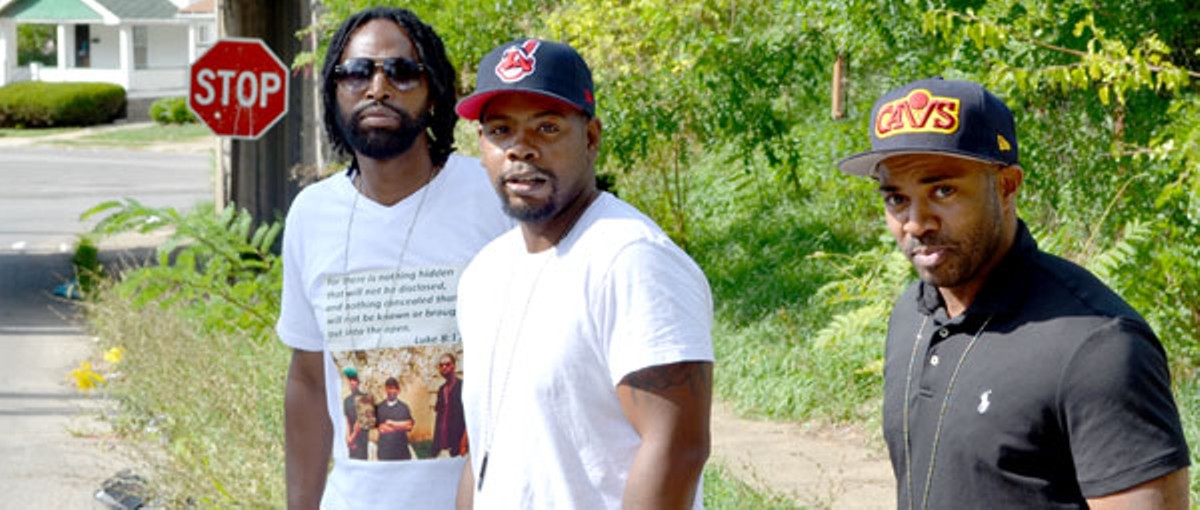

What was done to Johnson was also done to his friends, Derrick Wheatt and Laurese Glover. Friends for decades, they're joined forever as a single entity: the East Cleveland 3. They've returned to Strathmore today, rewinding their lives back to February 1995. Since their release from prison last year, they say, each of them has avoided this place, the intersection of Strathmore and Manhattan. They didn't shoot that guy; they should have never been caught up in that whole mess.

"This is where the nightmare begins," Johnson says, while cars breeze toward the stop sign under the bridge. As the three of them point out the precise location of the shooting, they can't help but comment on how much the street has changed since then. Wheatt, half-joking in a quiet voice, compares the neighborhood to what you might see on The Walking Dead, a post-apocalyptic "after" picture of what happens to a place when everything falls apart.

A lot of things fell apart in East Cleveland over the years, as gun violence became a motif in a city struggling with drugs and poverty and a declining population. The sound of gunfire on a Friday night back then could be anything: a gang dispute, a crack deal gone south, the sort of high-wattage domestic disturbance that might explode behind the walls of any home in this country.

But why was a man named Clifton Hudson shot and killed here on Feb. 10, 1995? It's difficult to say. Long-hidden evidence flashes scant light on potential leads; the investigation into his murder stopped short of the truth.

Rather, three teenagers were arrested and later convicted. A story was crafted on the word of a nerve-wracked 14-year-old walking home from school that day, and the records behind the investigation were kept from the public view for many years. Those teenagers became the East Cleveland 3 and, many years later, when the East Cleveland 3 were men, once everything got sorted out, their journey became a symbol for the rot within our criminal justice system.

"It was crazy how it happened," Glover says now. "Throughout the years, I always said it was written. It was meant to happen to us."

"We was just some carefree kids growing up in the inner-city," Wheatt says.

"Wrong place, wrong time," Johnson adds, shaking his head.

***

The sun was setting early on the evening of Feb. 10, 1995, and Glover was cruising with his friends. He had just bought a '79 Blazer, a honking beast of American metal. In the mid-90s, you couldn't pull out of your driveway without seeing one rolling through the East Cleveland neighborhood. Glover was happy. Being all of 16 at the time, a sophomore at Shaw High School out with his buddies, what else was there to do besides joyride? "People were jumping in and out all day," Wheatt recalls.

"At the end of the day, it ended up just being us three," Glover adds, motioning to Wheatt and Johnson. Those two had been friends forever. Grew up a few houses from each other over on Ardenall. Glover rounded out the trio as they careened into their teenage years.

Here's what's happening: Wheatt's riding shotgun, and Johnson's in the back of the two-door Blazer. They're trucking north along Strathmore. Home is just around the corner.

Clifton Hudson, 19, is walking on the sidewalk. He'd been through a hell of a week so far. Just the day before, in fact, he was telling his brother Derek that some guys had pulled a gun on him. Derek told him that guys always think they're tough when they've got a gun on their side.

And he'd know. Earlier that week, according to police records, some other guys had pulled a gun on Derek, shooting several times from within a gray Chevy Cavalier near East 128th. He fled to a nearby convenience store, safe but concerned. Something was up.

On Feb. 10, as evening slid into view, Hudson had just gotten to the neighborhood after cashing a check nearby. According to witnesses, he looked like he was waiting for someone on Strathmore. Glover and his friends are driving up the street. Another man is walking out of the parking lot of the East Cleveland Post Office, a ragged glut of asphalt that spills onto Strathmore.

Like every other time, Glover stopped at the stop sign attached to the railroad bridge overhead, just short of the intersection with Manhattan Avenue.

And then: gunshots, abrupt and rapid.

Glover hit the gas and took a hard right onto Manhattan. The weird thing about this intersection, you see, is that the stop sign on Strathmore is set way back from Manhattan; you've pretty much got to stop again once you pass under the bridge. Glover didn't even bother. ("I almost hit a car and everything," he says.) He was frightened, and he tore off into the night with his friends, leaving a few bewildered observers with the vision of a black Chevy Blazer fleeing the scene of a shooting.

Back on Strathmore, Hudson lay dying in front of a blue house after a few bullets pierced his left arm and chest. A man was seen rifling through Hudson's pockets before running off and dashing up the hill onto the railroad tracks. (Cash amounting to $166.51 was found in Hudson's jacket later on.)

Hudson was declared dead at 6:28 p.m. Within hours, police officers arrested three suspects.

***

An investigation unfolded briefly that winter. Defense attorneys would later call this a classic case of tunnel vision. East Cleveland detectives pounded the pavement in the days after the murder, gathering witness reports from about a dozen people of all ages. Some of them saw the shooter, some didn't, but all offered worthwhile perspectives.

Everyone involved was confident that this thing would be wrapped up soon: The three kids figured they'd be home in no time — they had never even heard of this guy Clifton Hudson, after all. For their part, the cops knew that they had people in custody for a murder on their streets. Done deal.

Looking back, Glover says, "If a dude would have come in with a gun and told them, 'I did it,' they probably would have been like, 'Nah, we got three people.'"

The framing of the events surrounding the murder began an hour after Hudson died, when a 14-year-old girl named Tamika Harris was brought down to the East Cleveland Police Department to answer questions about what happened. Officers had encountered her at the scene, where she explained that she was walking home from school — down Manhattan, toward Strathmore — when she heard gunshots. Her first statement sets the stage for the next 20 years.

"I had just come near the bridge, and we heard three (3) gunshots. Both of us ran to the bridge. [My friend, Monique,] turned and ran away. I looked around the bridge and saw this guy get out of a black 4 x 4 with tinted windows. He pulled the gun from his pants and shot three (3) more times. I saw this guy standing on the street and he fell to the ground. The guy that he was shooting at was in front of the blue house where he was found on the ground. After the last shots, I heard the guy yell for help. After the guy finished shooting he looked around he had this black gun in his hands and while he was running he took the gun and tucked it under his jacket. When he got to Manhattan he was still looking around, I saw him and hid flat against the bridge. Before the guy ran towards the bridge whoever was driving the 4 x 4 pulled off and turned right onto Manhattan. He almost crashed into another car coming off Manhattan. They drove fast towards Shaw and stopped, the guy that did the shooting ran to the 4 x 4 got inside and it turned left on Shaw headed towards Hayden."

When asked if she could identify the man who fired the gun, Harris replied, "No. I didn't see his face that clear."

Overnight, police searched and soon found a black Chevy Blazer parked at the bottom of Glover's driveway. After waiting around to make contact with the owner, police saw Glover and Wheatt get into the car. They arrested the two immediately. Johnson was arrested at his home; his mother joined him en route to the police station.

The 14-year-old girl was seated opposite detectives once again the next day, being urged to recount what would become the prevailing narrative of the crime. In short order, she identified Johnson as the shooter. Presented with photos of three men – Johnson, Glover, Wheatt, all in custody by then – Harris selected Johnson.

The die was cast.

Between that point and the January 1996 trial, detectives continued to build supplemental reports, interviewing multiple neighbors whose words would not be heard publicly until almost 20 years later. Defense attorneys themselves weren't made aware of the extent of the investigation, limited as it was, and so they presented only two witnesses who did indeed insist that the shooter was not one of the three men facing charges. They never had a shot at mounting a full-bodied defense, though.

The county prosecutor ran with Harris' storyline, using gunshot residue found on Wheatt's hands and on a glove inside Johnson's jacket as the basis for a "two-shooter theory." Assistant County Prosecutor Michael Horn painted a picture of Wheatt shooting from the front passenger seat before handing the gun back to Johnson, who exited the vehicle to approach and kill Hudson (and then chased the Blazer onto Manhattan and jumped back in).

As the trial wore on over a few days, however, Harris changed her story again and testified that she never saw the shooter emerge from the vehicle. Rather, she saw a man walk around the back of the vehicle — from the post office parking lot — and confront the victim before pulling a gun and shooting him.

"I remember like it was yesterday," Glover says. "Tamika testified on a Friday. And I remember going home that Friday, and for everybody that wasn't there at trial I'm telling them we got this. We've beaten it. Because that's their only witness — and all the stuff she was up there saying, like, 'I made a mistake. I corrected it.' It was just too much. It was bad. I just knew there was no way we could get convicted after that."

The following week they were each convicted on murder charges. They declined to plead guilty for lesser sentences. As their trial attorneys urged a plea deal, the reality of how deep this hole might go was only just beginning to settle in.

"I started getting a little scared then," Glover says. "Like, I'm 17, going away for murder — for life."

Glover was sentenced to 15 years to life in prison. Johnson and Wheatt picked up 18 years to life. As part of the sentence, Johnson, the one who allegedly finished the murder, was ordered to be placed in solitary confinement every year on Feb. 10, the day Clifton Hudson died.

***

Time marched on, hand in hand with the sedate pacing of the appeals process. The East Cleveland 3 kept busy with paperwork and legal study.

In 1998, then-Mayor Emmanuel Onunwor of East Cleveland was raising vocal doubts about the convictions of Johnson, Wheatt and Glover. He pushed the police department and rooted around for information that might fill some of the obvious gaps in the crime narrative. There had to be more than seven pages in the case.

That's when the county tossed its weight back into the arena, the reputation of its prosecuting attorneys hinging on a dubious case that was still stirring protest in the neighborhood.

First, Assistant County Prosecutor Carmen Marino (later to serve as county prosecutor) sent a letter to Sgt. Terrence Dunn of the East Cleveland Police Department in June 1998.

"It has come to our attention that the City of East Cleveland intends to release the police file of the investigation of the above captioned case. It is our position that said police file and its contents are not public record, thus any release could constitute a willful violation of the law.

"You are hereby directed to turn over to the Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office Investigator presenting this letter the entire department file concerning the above captioned matter, including, but not limited to, all items of the file contained within the Detective Bureau as well as any and all copies which exist elsewhere, including, but not limited to, the Records Room of East Cleveland. Said file and all contents are to be handed over to Cuyahoga County Prosecutor's Office Investigators forthwith."

What happened in the wake of that letter is hazy, as most — if not all — of the documents contained within the police report did remain in East Cleveland over the years. Had the police department complied, the documents might have been buried in the back room of the prosecutor's office. The truth might have been shredded immediately.

Still, pressure was exerted, and the police report disappeared.

But people in the neighborhood continued to talk, and by the time the Ohio Innocence Project came onboard the case in 2006, a wave of engaged legal expertise was coming down on the East Cleveland Police Department. There had to be more to the story, after all these years.