Meet the People of 2017's Cleveland People Issue

By Scene Staff on Tue, Jul 18, 2017 at 10:51 pm

AKeemjamal Rollins

Slam Poet and Educator at the LGBT Center

Most poets are happy to get a smattering of applause for their efforts, so it's unusual, and stirring, for a poet to receive a standing ovation. And it's particularly notable when that tribute comes from your high school classmates.

But that's what happened to AKeemjamal Rollins after he read a poem in school at 13 years of age. "As I recall, the poem was based on some vocabulary words, such as 'rueful.' When I was done, all the kids stood and applauded. I guess that's where my poetry career began."

Since then Rollins has made quite a name for himself in slam poetry circles, in Northeast Ohio and nationally. Last year, the local team he coached finished in seventh place at the National Poetry Slam in Decatur, Georgia, out of 72 teams. (Slam poetry, for the uninitiated, is a poetry competition in which poets read their poems and are scored by judges randomly selected from the audience.) He is also the coach of this year's Northeast Ohio slam team, The People, competing at the nationals in Denver later this summer.

Rollins has also competed in 10 other national events, as well as countless local and regional slam fests. During these intense competitions, audience members are encouraged — nay, summoned — to yell, cheer, boo, scream and react vocally in any way that moves them. In short, it's a blast.

Rollins is a master of the craft, using his background as theater performer and his gift for writing compressed, evocative language to win over virtually any audience he encounters. As Rollins says, "To succeed in slam poetry, you have to be your true self, you have to dig deep to the roots. What an audience sees in a slam event are the branches and leaves, but if the roots aren't there, the poem won't work."

Actually, Rollins didn't write about himself until 2013, but since then he's been exploring all aspects of his own roots. An example of that is when Rollins writes about his little brother Rashad who is on the autism spectrum. Rollins was astounded when one day, out of the blue, the 21-year-old Rashad said, "AKeem," since Rashad had never said his brother's name before. As Rollins explains it, "Whenever I write about my brother, I become present. I re-enter my body."

Here are two haikus Rollins has written about his brother:

He is not a thing

I don't have an autism

I have a brother

He knows shooting stars

Are angels playing Frisbee

Using their halos

When he's not slamming, Rollins works as a prevention educator at the LGBT Community Center of Greater Cleveland, teaching comprehensive sex education to teens from 14 to 19 years of age in Cuyahoga County. He is in his second year of that work at the Center, and he looks forward to pursuing an Applied Behavior Analysis license in the future, so he can work with patients dealing with autism and related disorders.

With AKeemjamal Rollins, the roots run deep and wide. — Christine Howey

Aparna Bole

Pediatrician, Medical Director for Community Integration, Sustainability Director Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital and UH

We caught up with Dr. Aparna Bole on a classic Cleveland morning, gray skies shifting seamlessly into sunny, cerulean blue and back again. From our vantage point on the rooftop of Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital at UH's main campus in University Circle, the city beamed with energy. Walls of flowers bordered our conversation as Bole described how she got to her current positions and what she's looking forward to continuing to accomplish.

"In health care, we're becoming more and more aware of how much we need to widen our lens if we're serious about improving the health of the populations we serve," she says. She started the health system's sustainability office in 2010, blending the themes of waste reduction, energy management, sustainable purchasing, healthful food, green buildings and an overall sense of wellness into a massive institution.

This is a major motif in Bole's work: identifying how the environmental context of a patient — the stuff in between medical procedures and check-ups — affects his or her health. With a rapidly changing healthcare business ecosystem and a rapidly changing climate, this sort of paradigm shift is paramount for places like UH. Bole is on the vanguard.

Besides her two primary titles at UH, Bole remains a practicing pediatrician. And that's where her work has seemingly been most visible, by taking a close look at how climate change and its air quality effects end up impacting our community's most vulnerable population: children. This manifests as advocacy through health care operations, setting an example for local legislators and air quality control leaders. The key, Bole has noticed, is that government policy needs to be treated as a health issue. What is the home environment for Cleveland's children like? What decisions have been made to improve the places where young Clevelanders grow up?

"Ten to 20 percent of a population's well-being is determined by access to excellent health care, and that's great and we want to continue to provide that," she says. "But if we really want to improve our community's overall well-being, we need to focus on social, economic, environmental, physical issues in the community."

Cleveland is a great place to do just that. After growing up in Portland, Oregon, where environmental leanings have been a social constant for a long time, Bole landed in Cleveland to find a city that's situated perfectly to do even more to improve its footprint on this world. With a public transit system traversing roadways conducive to cycling and walking, Cleveland's old bones provide its current residents a platform to develop new, more sustainable community assets. The entrepreneur set has started companies that are built on green and eco-friendly models, which in turn benefit all neighbors. In the heart of it all, Bole finds optimism and enjoyment.

"How lucky are we?" Bole says. "We have plenty of fresh water, we have these incredible bones in our city — this architectural richness and incredible cultural diversity. If you think about the challenge and opportunity of the American city, Cleveland embodies that for me in a way that's really exciting and positive." — Eric Sandy

Brandon Luis Santiago

Owner, Woodworker, Cleveland Hardwood Restoration

One thing that Brandon Santiago does is cart around small pieces of finished lumber and leave them places, like small tokens or like a special bonus tip when he's leaving a restaurant. Sometimes he just gives them to people. Today, when he comes to meet Scene at Working Class Brewery in West Park, he's carrying a small piece of purpleheart finished with an eco-friendly mono coat.

But that's just one thing, because Santiago is a busy man.

Santiago started Cleveland Hardwood Restoration six years ago after a few jobs and several years of training under a bona fide flooring master. "I studied him," Santiago says, "and really studied to be better than him. I'm the type of person who ... whatever I put my hands on, whether it's making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or sanding a floor, I want to do the best."

He got his start by working in a vegan kitchen in Westlake. This goes all the way back to his childhood, helping his uncle tear down walls and build the place. When he hit 20 or so, his first child came along, and Santiago started thinking about where his life would take him. Naturally, he quit the job.

The guy who owned the building offered Santiago some work just two days later. The gig involved floors, and Santiago dug in. "The floor was being sanded from the most disgusting state — and one rip from the machine and the wood looked brand new. My first, lasting memory was just walking into this house and seeing this and being like, 'Holy shit. This is really cool.' I fell in love with the craft from Day 1."

With that last sentence, Santiago nods to the cover of Hardwood Floors magazine's 2017 Resource Book. There he is, on the cover of the industry's most important publication. That very same quote adorns a photo of Santiago in his workman's denim. It was the first time the magazine had ever featured a person on its cover.

In just a short amount of time, Santiago's Cleveland-based spirit and DIY attitude has given him some level of celebrity in the hardwood restoration world. His Instagram account, @clevelandwoodbee, boasts more than 13,000 followers. Through his photos, he showcases that very same feeling that first inspired his love of the craft years ago. This is another thing that Santiago does.

During our conversation, a brewer stops by and shows Santiago that he's still carrying the small piece of wood that he was given a few weeks back. This would be the ripple effect of Santiago's presence.

Originally, the mission was small and simple. But demand for Santiago's work has grown fast, and he's picked up a few employees and trained them himself — just like his own path not too long ago. With that, Santiago's been able to define how he wants to run a company: good pay for a job well done with eco-friendly, socially conscious materials. (Cleveland Hardwood Restoration uses Rubio Monocoat natural oil finish, which sets him apart from the chemical-laden competition. "Let the wood be the wood," Santiago says.)

Before the magazine, and the company, and his family, though, Santiago very nearly missed out on his life altogether. A few days after his Lakewood High School graduation, he was pitching in a game at Clark Field in the West Denison Baseball League. He was hit hard with a baseball, blinding him completely in his right eye.

"I've been told it could have killed me: the amount of damage that it did to my eye itself," he says. "To think that that could have been it, right there, makes me kind of feel like I only have one shot at this life. So let's start a hardwood floor business, let's hire some guys, let's buy a van. Let's just ride the wave, because who the eff knows?"

In so many ways, Santiago has carved his dream out of that ethos of hard work. It's the classic Cleveland story, and he's excited about the road ahead.

"The next floor will come," he says. "I'm a big believer in Cleveland." — Eric Sandy

Brett Jones

President, Evergreen Energy Solutions

Lights, lettuce and laundry. It's alliterative shorthand for employees of Evergreen Cooperatives that basically describes the employee-owned operation's three areas of business. There's Evergreen Energy Solutions (lights), which encompasses work in LED installation and construction; Evergreen Laundry Cooperative (laundry, of course), which does large- and small-scale work for nursing homes, hospitals and more; and Green City Growers (lettuce), the 3.2-acre hydroponic greenhouse in the Central neighborhood that grows all kinds of lettuce for area restaurants and for further distribution.

Evergreen began back in 2008 with the laundry facility, then the energy solutions business, and finally the greenhouse in 2012. There have been bumps in the road, but lights and laundry are profitable and lettuce is projected to be this year.

Shaker Heights native Brett Jones is the president of Evergreen Energy Solutions and is part of the leadership team that's helped guide the businesses, which employ around 140 people, 60 of whom are members. (Employees can join the co-op after a year.) The whole "mission" aspect of Evergreen wasn't something he initially "got" when he started.

After high school, Jones went to Ohio State, finishing his degree while he was abroad in South Africa. He was a Fulbright fellow and got into global logistics (freighting), founding and working at a handful of businesses before being recruited to run Tri-C's workforce program. It wasn't long before Evergreen sought him out — they were working on a solar project at the time — and Jones signed on to help them with top-line growth in 2012.

"I understood the mission aspect a little at first," he says over coffee at Dewey's in Shaker Heights, where he lives in the house where he was raised, and where his mother was raised before that. "But I wasn't a community development or economic development guy. I was a business guy. So I wondered how we were going to do all this mission stuff, but after six months, I got bit by the bug. It's a reason to get out of bed in the morning.

Jones answers 10 questions when he's asked one. It's an "if this happens, then this happens, and if that happens, then this happens" proposition, all bubbling with passion. For example, Evergreen will find out later this year whether it's the recipient of $5 million of the $100 million available from the Quality Jobs Fund, founded by Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco and the New World Foundation with the goal of enhancing local wealth and creating long-term sustainable working families. If Evergreen receives the funding, Jones says it will be a game-changer with ripple effects.

"That will allow us to convert existing businesses into worker-owned co-ops," he says, noting they'd focus on industrial businesses in Cleveland, like tool and die operations. "You have these places where a current owner wants to retire, and they're not private-equity sized companies, but maybe they're attractive to offshoring. So you're converting them to worker-owned, to stay here. There are a lot of baby boomers who are ready to retire and business that may move or close. That devastates local economies, when you lose 10 or 20 jobs in aggregate. That industrial base in Cleveland is still strong and we want to keep that here.

"Motives change when employees own the business," he says. "When you talk about quality jobs, higher wages are part of that conversation, and benefits packages, and opportunities to not only have a living wage but to share in the profits of a company. We can create a new ownership class in America, close that income inequality gap, improve lives, create a new economic class."

Evergreen's living it. Employees, many of whom are refugees or ex-convicts, get access to financial training and affordable mortgages; members attend quarterly board meetings and vote on issues affecting the business and share in the profits. There may be 140 now, Jones says, but there will be more, especially in the LED and energy divisions.

"A new ownership and economic class," he says. "That's the stuff that gets you out of bed in the morning." — Vince Grzegorek

Brianna Jones

Owner, Lush and Lovely Floristry

Stepping into Lush and Lovely Floristry in Ohio City for the first time, your nostrils are bombarded by an earthy sweetness. It's an entirely unique sensory experience for visitors, but for owner Brianna Jones, it barely registers any more. This is the building where she spends most of her time, after all. When not on the first floor caring for her plants, two birds and loyal customers, she's upstairs looking after her children or studying for business classes at Cuyahoga Community College. Sleep is rare.

Lush and Lovely opened in October, and already Jones says the shop has built up a slew of regulars, many of them women in their 20s. Flowers, succulents and other green things are especially popular among the younger demographic, Jones says. Slide through any fashionable millennial's Instagram feed and you'll notice artfully posed women among green and neutral tones.

"Millennials in particular, we have a need to be environmentally friendly," the 31-year-old explains from a highly Instagrammable corner of her shop. "The plants bring you closer to nature, and there's this new spin on floral designs that makes it exciting."

Rather than tight bouquets, many young women (brides in particular) are looking for a loose, organic, garden feel. "It's the dahlias and peonies, versus roses and carnations," she says. "I think we're seeing a lot of younger people becoming florists too. It's not just your grandma's florists on the scene anymore."

This modern resurgence is part of what got Jones into the industry.

Growing up near the Poconos Mountains of Pennsylvania, Jones says she was always a "flower picker" and her mother always filled their home with plants. Later, after being stationed with the Army in Afghanistan (where the only flowers grew in the poppy fields), Jones went to art school in Georgia. Last year, when her husband also got out of the service, they decided to move to Cleveland, where her grandparents live.

"My husband and I had been talking about the possibility of opening a floristry shop, but it wasn't serious. It really only became an idea last summer," Jones says. "But when I make these rash decisions, I am all in. I did the same thing with the military. I just stopped in a recruiting office randomly and a couple weeks later, I shipped off to boot camp."

From the beginning, when Jones opened the shop with her sister Brooke Witt (who has since left the business), Lush and Lovely has hosted monthly workshops, teaching people how to make hip crafts like flower crowns and succulent tea cups. Jones also focused on keeping costs low (bouquets start at $20), while sourcing as much as possible from sustainable farms.

Now, nearly a year in, the entrepreneur says she feels at home, personally and professionally.

"For some reason I've always had a strong connection to Cleveland; since first visiting, I always knew I wanted to live here," Jones says.

"I was a nobody and I just opened this shop, and I didn't know anyone here, but people have been so supportive." —Laura Morrison

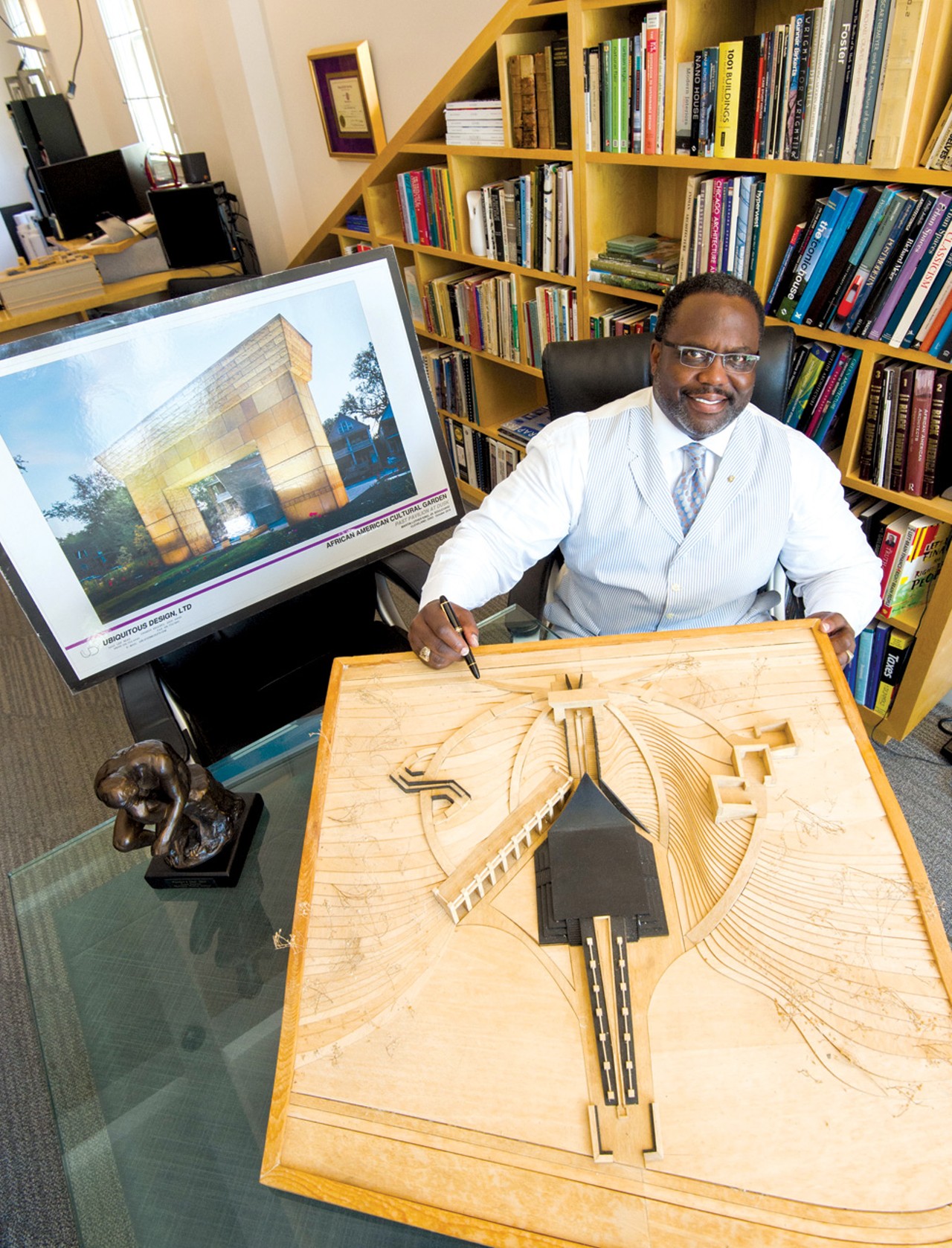

W. Daniel Bickerstaff

Principal, Ubiquitous Design, LTD

When architect Daniel Bickerstaff realized, with a start, that he wasn't just on the design subcommittee for the African-American Cultural Garden, he was in charge of spearheading the design, he went six months without picking up a pencil.

"That's unheard of for me," says the Shaker Heights resident, speaking at a conference table in his firm's office on Lee Road. "But I really wanted to understand this dual citizenship — this idea of being both African and American — before I put my ideas down."

Bickerstaff says during his extensive research of the harrowing Middle Passage and the experience of African-Americans in the United States, he would often find himself weeping at his computer screen.

"I'm a big guy, 285 pounds," says Bickerstaff, "but it was that emotional."

Bickerstaff, whose father is from Alabama, says he never discussed race with his family but that he sees the importance — no, the necessity — of doing so. "Just like our Jewish brothers and sisters," he says, "this country must embrace and express our history, even the awful parts. In doing so, we pay respect to those who survived. That's why I'm sitting here in this air-conditioned office."

Bickerstaff grew up in Hough (the 8200 block of Superior) and attended Cleveland public schools until the 10th grade, when he won a scholarship and finished high school in Boston. Afterward, he attended Washington University in St. Louis to study architecture, in defiance of a prominent professor who encouraged him to switch to social work. Energized, and proud of his academic accomplishments, he returned to Cleveland in 1986. After working in the private sector for a few years, he worked in the city's planning office. He was Mayor Michael White's chief architect before he set out on his own in 2002.

Since that time, his firm, Ubiquitous Design, LTD, has worked on an array of local projects. Bickerstaff has a passion for historic preservation and designed the Men's retail clothing store at Clifton Boulevard and Lake Avenue that used to be a BP gas station. He designed the red and metallic contemporary condos on Brayton Avenue in Tremont. He has designed churches and hotels and local parks.

(In case you're wondering — we couldn't resist asking — Bickerstaff's favorite building in Cleveland is the Terminal Tower. He worked there fresh out of college and has fond memories of, among other things, the fountain. He says he looks forward to what Tower City can be again, now that a sufficient downtown population exists to patronize the businesses there.)

But his crown jewel remains the cultural garden. Though only the $600,000 first phase of the $2.5 million project is complete, the finished portion is already an important symbol for Cleveland's African-American community. The garden was originally dedicated in 1977, but a committee to raise funds and build the memorial wasn't established until 2003.

The completed portion includes a large archway and a black corridor that signifies the Doorway of No Return in West Africa.

"These are torturous things we're representing," Bickerstaff says, of his concept, "but I wanted the design to be beautiful, to be elegant, and to be something we're proud of as a community."

Bickerstaff says the fundraising for the remaining phases is ongoing, and that he'll be involved until the final stone is laid.

"For me," he says, "it's a labor of love." — Sam Allard

![Daniel Gray-Kontar

Playwright, Teacher, Artist

"One thing I know," says Daniel Gray-Kontar. "I don't want to be 50 years old, rapping. All due respect to Snoop Dogg, I don't want to be running around on somebody's stage, saying, 'Throw your hands in the air like you just don't care.'"

Gray-Kontar is 46. The dusting of white in his goatee is the only visual evidence that he's not 10 years younger. He's a versatile writer and artist and says that he has always tried to find the medium that allows him to best express himself, the medium that makes the most sense for the times. In the past, that medium was journalism; in the past, it was hip-hop.

"Right now, it's poetry," he says. "Poetry allows the same capacity to play with language and rhythm and meaning, but without some of the restrictions of rap."

Performance poetry is also one of the key subjects taught and explored at the Twelve Literary Center, in North Collinwood, which Gray-Kontar founded last year. There, teenagers participate in a fellowship where they learn performance poetry and "various aspects of social justice." (Right now, five teens from Twelve are representing Cleveland in the Brave New Voices youth slam poetry festival and competition in San Francisco.)

In every aspect of his life and work, Gray-Kontar is committed to young people and advocating on their behalf. He was a creative writing teacher at the Cleveland School of the Arts for many years and has always believed that in society, "young people are often spoken at or spoken to.

"But it's incumbent upon us to listen," he says. "Young people live in this world too, and they often have answers that go overlooked."

One of the goals of the Twelve literary space, in fact, is intergenerational performance and dialogue.

"We've had conversations about race in this space," Gray-Kontar says, sitting on one of Twelve's comfy couches that form a perimeter around a performance area. "We've had conversations about class. We've had conversations about gender equity. The perceptions that young people have are different than those of older people. Both perceptions are equally valid, and that tension between them helps us unpack the issues. It's about mutual respect."

Gray-Kontar is also a recent addition to the Northeast Shores board of trustees. In that capacity he focuses on education issues and sits on the governance subcommittee. He says right now, he's intent on developing increased youth leadership opportunities.

It should come as little surprise that when he was tapped to collaborate on a play to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the historic Carl Stokes mayoral election, Gray-Kontar insisted on bringing youth on board.

"That was the one thing I said to [Karamu House president Tony Sias]," Gray-Kontar says. "I said I'm down. I just need to make sure young people are involved."

The resulting play, a 'choreopoem' called Believe in Cleveland, utilized documentary material, hip-hop lyrics and scripted dialogue. It was performed in June at Karamu and featured significant written contributions from local teens. Gray-Kontar says he's excited about the possibility of another run of the show (not at Karamu) later this year.

For now, though, he's thrilled to be at Twelve. He says when he was let go from from CMSD — like a lot of artist-teachers, Gray-Kontar didn't have his teaching certification — it was the first time he'd cried in a long time.

"But it turned out to be the best thing that could've happened," he says. "Now I can bring the same message I taught at [Cleveland School of the Arts] to youth all over Northeast Ohio."

— Jeff Niesel](https://media1.clevescene.com/clevescene/imager/meet-the-people-of-2017s-cleveland-people-issue/u/zoom/38252522/dan-kontar076.jpg?cb=1648285590)

Daniel Gray-Kontar

Playwright, Teacher, Artist

"One thing I know," says Daniel Gray-Kontar. "I don't want to be 50 years old, rapping. All due respect to Snoop Dogg, I don't want to be running around on somebody's stage, saying, 'Throw your hands in the air like you just don't care.'"

Gray-Kontar is 46. The dusting of white in his goatee is the only visual evidence that he's not 10 years younger. He's a versatile writer and artist and says that he has always tried to find the medium that allows him to best express himself, the medium that makes the most sense for the times. In the past, that medium was journalism; in the past, it was hip-hop.

"Right now, it's poetry," he says. "Poetry allows the same capacity to play with language and rhythm and meaning, but without some of the restrictions of rap."

Performance poetry is also one of the key subjects taught and explored at the Twelve Literary Center, in North Collinwood, which Gray-Kontar founded last year. There, teenagers participate in a fellowship where they learn performance poetry and "various aspects of social justice." (Right now, five teens from Twelve are representing Cleveland in the Brave New Voices youth slam poetry festival and competition in San Francisco.)

In every aspect of his life and work, Gray-Kontar is committed to young people and advocating on their behalf. He was a creative writing teacher at the Cleveland School of the Arts for many years and has always believed that in society, "young people are often spoken at or spoken to.

"But it's incumbent upon us to listen," he says. "Young people live in this world too, and they often have answers that go overlooked."

One of the goals of the Twelve literary space, in fact, is intergenerational performance and dialogue.

"We've had conversations about race in this space," Gray-Kontar says, sitting on one of Twelve's comfy couches that form a perimeter around a performance area. "We've had conversations about class. We've had conversations about gender equity. The perceptions that young people have are different than those of older people. Both perceptions are equally valid, and that tension between them helps us unpack the issues. It's about mutual respect."

Gray-Kontar is also a recent addition to the Northeast Shores board of trustees. In that capacity he focuses on education issues and sits on the governance subcommittee. He says right now, he's intent on developing increased youth leadership opportunities.

It should come as little surprise that when he was tapped to collaborate on a play to celebrate the 50-year anniversary of the historic Carl Stokes mayoral election, Gray-Kontar insisted on bringing youth on board.

"That was the one thing I said to [Karamu House president Tony Sias]," Gray-Kontar says. "I said I'm down. I just need to make sure young people are involved."

The resulting play, a 'choreopoem' called Believe in Cleveland, utilized documentary material, hip-hop lyrics and scripted dialogue. It was performed in June at Karamu and featured significant written contributions from local teens. Gray-Kontar says he's excited about the possibility of another run of the show (not at Karamu) later this year.

For now, though, he's thrilled to be at Twelve. He says when he was let go from from CMSD — like a lot of artist-teachers, Gray-Kontar didn't have his teaching certification — it was the first time he'd cried in a long time.

"But it turned out to be the best thing that could've happened," he says. "Now I can bring the same message I taught at [Cleveland School of the Arts] to youth all over Northeast Ohio." — Jeff Niesel

Deb Sherman

Owner, Aut-O-Rama Twin Drive-In

The Aut-O-Rama in North Ridgeville wasn't the first drive-in theater in Cleveland, but, in 1972, it was the first to offer two screens. "We actually opened this after the big wave of drive-in theaters in the 1950s," says Deb Sherman, the owner. "So ours looks a little different. We learned from the others what worked and what didn't."

It was birthed seven years before the addition of the second screen, back in 1965, by Sherman's late husband's family. Her father-in-law wasn't necessarily a film lover; he was more of a businessman, always looking for new ideas. Thus, the second screen.

Sherman's husband and his brother joined their father in the business shortly after he opened it, and it's been in the family ever since, with all five Sherman children helping her run the place since her husband's death in 1993. Three of the kids have since moved away, but sons Tim and Del are still around to help their mom.

"I wouldn't be able to do it without them," Sherman says. "I've got three grandkids that are local, and they'll help out and be here just about every night, and if we don't burn them out, hopefully they'll be around here for a while." Sherman's 8-year-old granddaughter runs the register, while her 10-year-old grandson will be popping popcorn and running pizza orders.

Ohio is actually the leading state for drive-in theaters, along with Pennsylvania. "There are 26 in Ohio, last I heard," Sherman says. The Buckeye State's temperate climate lends itself to the industry, as does the local love of automobiles.

"One of my theories," Sherman says, "is that it's part of the whole car climate of this area, with all the car manufacturing back in the days, and people just love their cars and doing things with their cars, and that's a big part of it, hopping in the car and staying in it and watching a movie from the car." The allure is part nostalgia, part functional, and part programming.

While they'll show newer movies, the attraction of combining a semi-old-timey outing with semi-old-timey movies has packed in the crowds. Sherman, in addition to doing everything including running the concession stands, is the chief curator.

"The films from the 1980s are always the most popular," she says. "Pretty in Pink, Weird Science, Sixteen Candles. That's what people like to see. And I look down the list of what was popular in each decade and choose based on that, but the '80s draw the best."

Coincidentally, the 1980s is also when drive-ins were really struggling — when cable television came out, when the VCR became popular and video stores were big and people were staying home. "That was a really rough decade for us and that's when most of the drive-ins around here closed." But Aut-O-Rama stayed open, and while there have been ups and downs since then, it's been pretty steady the last couple of decades, and since digital projectors were installed in 2013, they have seen an uptick in customers. With half a century in the books, here's to another. — Brett Zelman

Eric Rogers

Chef-Owner, Fix Bistro, Sweet Fix

At the age of 19, and with nothing resembling an advanced degree, Eric Rogers was employed as a file clerk by University Hospitals. His work ethic, confidence and optimistic personality helped him scale the corporate ladder all the way to finance manager.

"I've always been a hard worker," he says. "Anything I do, I do with full force. That's how I was raised."

Much of what Rogers needed to know, he learned in his grandparents' East Cleveland restaurant, where he began working at the age of 8. He started off small, cleaning greens, snapping beans, peeling potatoes. But by the age of 13, he was the restaurant's head cook.

"Customers started coming in and saying, 'I want the little guy to cook my food,'" Rogers recounts. "That's when I started taking it more seriously."

Even during the Desk Job years, Rogers never fully put away the apron. His backyard barbecues drew crowds, his guests shifting from family and friends to paying customers. At 33, he made the decision to walk away from his corporate gig and follow his heart.

While his wife was unconditionally supportive, Rogers' parents thought he was crazy. But all those years poring over the hospital ledgers provided him with a degree of financial aptitude that many fledgling entrepreneurs lack.

"I didn't just jump off a building: I planned," he explains. "I created a business plan, did market analysis, looked for a void in the community ... I took a professional approach, and at the end of the day, I knew I couldn't fail if I had a great product."

First came Nevaeh Cuisine, a Creole- and Cajun-style eatery in South Euclid, which he quickly traded in for a "great little corner spot" in Cleveland Heights. Rogers took his soul/Cajun leanings and reshaped them into a "fast-gourmet" sandwich concept called Black Box Fix.

"I knew this area would appreciate what I do," he says. "I was creating food that this side of the city had never seen before. After that it was like, boom, everything blew up."

You could call Black Box the restaurant that OMG Phillys built. That immensely popular hoagie consists of sauteed chicken, peppers and onions capped with plump seasoned shrimp, and thousands were selling each week.

When a larger space opened nearby, Rogers eagerly expanded into a full-service restaurant called the Fix Bistro. In his old spot, he partnered with a baker to open Sweet Fix, a neighborhood bakery. This summer, Fawaky Fix, a partnership with the owner of Fawaky Burst Juice, will open on the same road. Soon after, Soul Fix, a healthy soul food carry-out, will open down the road.

But the move that Rogers seems most pleased about is the chance to take the Black Box Fix concept to Legacy Village.

"They called us, and that was something that made us very proud, being one of the first black-owned businesses to go in Legacy Village," Rogers says. "It's a whole different market, and we have to prove ourselves, but I think it's a model that crosses cultural borders."

Does Rogers ever pine for the relatively tranquil days working the desk?

"I love what I do, and the fact that my wife is now doing it with me definitely helps," he reports. "I wake up every day and do what I love, so I never feel like I'm working. You can't beat that in life." — Douglas Trattner

Freda Levenson

Legal Director, ACLU Ohio

There will come a time when America's lovefest with the ACLU will end, or at least taper off. Freda Levenson knows this.

The Trump administration and its attendant policies and rhetoric put the legendary civil rights organization in the spotlight, especially after it battled the president's Muslim Ban.

"The ACLU has brought some of the foundational Constitutional cases, we have a long history, but we're not your grandmother's ACLU," says Levenson, the legal director of ACLU Ohio, in her office one June afternoon. "We're as fresh and relevant as ever, and we can partly thank President Trump for that. When he was campaigning, the rhetoric was so laughable and not credible, but the ACLU took his promises seriously and we were prepared for legal challenges. So when he made good on promises to cut back rights, the ACLU was ready."

In one weekend following their first victory over Trump's Muslim Ban, the ACLU received $24 million in online donations from more than 350,000 individuals. "Our membership swelled," Levenson says, "and people that maybe hadn't noticed the ACLU were calling us heroes."

That has been great, in exposure and pure monetary terms. The donations allowed for additional hiring, but the ACLU has only about 300 staff attorneys nationwide compared to some 19,000 government lawyers — "We're still David to Trump's Goliath," she says — but it's untenable. Folks who pledged support who might think the ACLU exists to fight Trump might not like it when that portion of their work doesn't continue to populate headlines, or if and when the ACLU represents someone they disagree with.

"It's not going to last forever," Levenson says. "And we're very proud of the work we do that's also the opposite of taking on Trump." They represented Citizens for Trump during the RNC, for instance. Levenson also cites the famous 1970s case when the ACLU represented neo-Nazis and their right to march in Illinois.

As ethics and morals become fungible and flexible based on partisanship, strange bedfellows is a useful test to see if a person or organization hews to the straight and narrow points of their mission. The ACLU passes with flying colors. "We're an equal opportunity pain in the butt," Levenson says. "We're staunchly nonpartisan. We represent people that we or you may disagree with, but it doesn't matter if their Constitutional rights are being violated. Free speech protects all speech, including hate speech, and our Constitution is designed in a way that if you disagree with something or find it offensive, the solution isn't to censor it, because then it goes underground. The solution is more speech."

Levenson calls the ACLU gig the "dessert of her career." She grew up in Shaker Heights, went to Wellesley, then to the University of Michigan for law school. She landed a job as a commercial litigator and eventually became partner at a large Chicago law firm when her professional status was a rarity.

"I was the second woman at a very large firm," she says. "A lot of people didn't understand that I was a lawyer. If I showed up to a meeting, someone would ask me to get them coffee. If I came to court, the judge would say, 'Miss, when's your boss getting here?' The lawyer's lounge at the firm, to get there, you had to go through the men's bathroom. If I wanted to go to a lounge, I had to go through the women's room to the secretary's lounge. It was a novel experience; times were changing rapidly. It was great training."

After moving back to Northeast Ohio, and as her four children grew older, Levenson taught as an adjunct professor at Case Western Reserve University and started volunteering with the ACLU. It wasn't long before she was hired as a senior staff attorney, then managing attorney, then legal director. While she praises her experience as a commercial litigator, it wasn't "as satisfying as combining your passion with your intellectual pursuit," she beams.

And while the ACLU continues to fight Trumpian battles, exceptionally important work is being done on the local level every single day, just like it's always been. In Ohio, Levenson and the ACLU fought a vital battle against the state for purging Ohio's voter roles. A 6th Circuit Court ruling sided with them, allowing the votes of some 7,500 Ohioans who otherwise wouldn't have had their votes counted in the November election, through an emergency temporary action. Which isn't the end of the battle: the Supreme Court will hear the case later this year.

"I'm living my dream," she says. "It's such a gift to work with your passion and always be on the right side." — Vince Grzegorek