"She's working on a series of scar portraits," he laughs. "She might be calling you up to see if you have a good scar."

The heart attack happened about three months ago, as Dixon and Jones were out running errands near their Canton home. Dixon started to feel his arm go numb and then experienced chest pains. They drove quickly to a hospital.

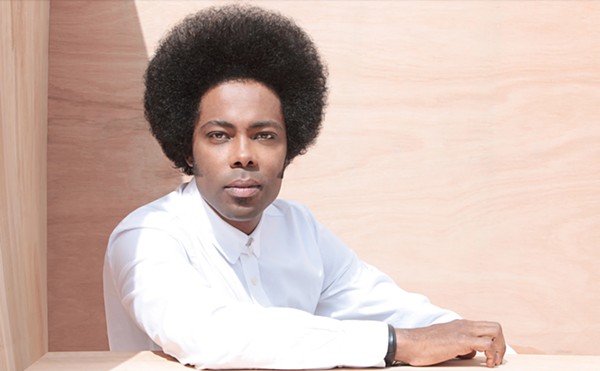

Like many musicians, the 50-year-old singer-guitarist doesn't have health insurance, so his trip to the emergency room came at a cost. While the incident didn't get any press locally, back in the Chapel Hill, North Carolina area where Dixon's originally from, a groundswell of support rose up. R.E.M., with whom he's worked, posted a plea for donations on its website, and relief funds were soon on their way. Dixon, who's on medication now, says he's been able to handle expenses, thanks to the band's support.

"It's been really hard, but R.E.M. really came through," he says. "They were really helpful. I've always been really good about health insurance and then, six or eight months ago, I just got pissed off about paying for it, so I stopped. And then I end up having a heart attack."

It's not surprising that Dixon's heart attack wouldn't have registered with the Northeast Ohio music community. Since moving here from Chapel Hill in the mid-'80s, Dixon has kept a low profile and hasn't produced any area acts. He doesn't play much locally, either.

"There just hasn't been something that I've gone crazy about from around here," he says. "I typically work with bands already signed."

Too bad. As Eric Olsen writes in The Encyclopedia of Record Producers, Dixon is "one of the pioneers of the organic, guitar-based side of '80s new wave." Initially, Dixon played in Arrogance, an obscure band that recorded a handful of records before dissolving in 1980. He then turned his attention to producing.

One day, friend Mitch Easter asked him over to the Drive In, the studio he had created in his parents' garage. He was working on an EP by a band from Athens, Georgia, and needed some help mixing it. That band was R.E.M. Though Dixon doesn't know whether any of his mixes made it onto the resulting "Chronic Town" EP, he was enlisted to help the band once again on Murmur, its full-length debut. That album stands as one of the best of the '80s.

"We worked hard and made a very good record," says Dixon, in his slight Southern drawl. "[Murmur] was a hard record to make. If we took everything they were doing on the surface and just made a document, it wouldn't have been as interesting. People talk about not being able to hear the vocals and all this stuff. It's not that you can't hear the vocals; it's just that you can't understand what [singer Michael Stipe] is saying, because he's saying shit like 'two-headed calf.' The sound of what was going on is important."

For Dixon, the '90s represent an era of missed opportunities. He was close to working on Nirvana's Nevermind ("the most excited I'd been about an album in a long time") and even met with the band for some early sessions in Seattle. But the group chose producer Butch Vig instead. "They got their way and decided they didn't need another asshole in the studio." He also unsuccessfully tried to get Hootie and the Blowfish signed to a major label. When the group finally did sign, Dixon didn't get to produce its major label debut, 1994's Cracked Rear View, which, like Nevermind, went multi-platinum.

While Dixon admits that it might seem as if he's "passed on all the good things," he's had his share of successes. His song "I Can Hear the River" was a hit in Germany for Joe Cocker, and he co-wrote the Counting Crows' "Time and Time Again."

Dixon says his health problem hasn't made him rethink his life. He never imagined he'd live long. While his next album, Note Pad #38, a collection of odds and ends, might seem as if Dixon is clearing the vaults while he still can, he says the album was nearly finished before his heart attack.

"I don't feel any more mortal," he says. "Growing up, life always stopped at 25. For me, there was no visualizing myself any older. I guess, at around that age, that's when I started to think that I was going to die. I don't have a preoccupation with it or anything, but I've been aware of it for a long time. It's a fun thing to think about, rather than a morbid thing."