A river runs through Collinwood made out of concrete and rusted railroad tracks. It's a dividing line, hemmed by unkempt weeds and plastic bottles, that you can cross without even knowing it, a stopover, a no-place, a between-place. But Jamar Doyle, executive director of the recently-formed Greater Collinwood Development Corporation, wants to bridge the divide.

Collinwood's river is I-90, says the 41-year-old nonprofit leader. It's the old Collinwood Railyards, a half-mile trench dividing the northern and southern parts of the neighborhood that was once one of the most active rail yards in the country, linking the industrial centers of the Midwest and Northeast. Today, it's a demarcating line separating white and black, middle-class and lower-income, trendy neighborhoods from ones that haven't even been thought of yet or were dismissed a long time ago.

Doyle says the highway and rail yards are his neighborhood's version of the Cuyahoga River, which has historically separated the city's whiter, more middle-class west side, which is known for having better schools, neighborhoods and services, from the city's blacker, poorer east side, which is known for its crumbling infrastructure, dilapidated houses and poverty.

"If you thought of this as our Cuyahoga, we have a lot of the same concerns, such as where is development going?" he says. "North Collinwood is seen as a more stable community, so how do we balance redevelopment of that area with efforts toward more equity and inclusion?"

"All of the east-west issues that Cleveland faces," he adds, "we face the same issues north-south."

People have been talking about reuniting Collinwood for longer than Doyle has been alive, but maybe that's precisely the point. Doyle is part of a new group of forward-thinking, collaborative leaders who are running Cleveland's community development corporations (CDCs), nonprofits that receive funding largely from the city but also from other sources to spur neighborhood redevelopment. These leaders say CDCs need a fresh approach, and they're focused on creating more equitable development patterns throughout the city, both east and west.

Doyle sees an opportunity to serve South Collinwood while continuing progress in North Collinwood, home to the Beachland Ballroom and Waterloo Arts District, both of which are fragile examples of the city's redevelopment. "There's a perception in North Collinwood that there aren't points of interest south of the freeway, whereas people in South Collinwood tend to feel that amenities north of the tracks aren't available to them," he says. "Neither is true."

These goals are ambitious given that there's less funding for community development than there was a decade ago. As the city's population has declined, so has Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) money that pays for CDC operations, from a high of about $40 million to $20 million per year. Declining resources have sunk many CDCs in recent years. Others have floundered or disappeared for other reasons, including mismanagement and malfeasance. Greater Collinwood CDC itself arose from the ashes of two failed CDCs that went belly-up.

A few years ago, when Doyle was working as assistant director at St. Clair Superior Development Corporation, he was approached by then-councilperson Jeff Johnson to become interim director at Collinwood & Nottingham Villages Development Corporation, where he was told director Tamiko Parker was out on temporary medical leave. However, it soon became apparent that in fact she'd stolen tens of thousands of dollars from the organization, among other things obtaining a $19,000 cashier's check from a CDC bank account to buy a car in Michigan, depositing paychecks twice in the amount of $30,000, and going on junkets to Las Vegas and Atlantic City. Within a few months, Doyle was tapped as permanent director.

By July 2018, he'd also learned that the director of Northeast Shores CDC was gone, and he was inheriting the organization's remaining staff. Nine months later, the board of Collinwood & Nottingham Villages created Greater Collinwood CDC with Doyle at the helm.

"Sometimes I joke, man, I need one year where things stay the same," he says with a laugh.

That's a big ask around these parts, but there's one bright spot to the declining resources and trimmer staffs: It has forced reorganizations, mergers and collaborations among Cleveland's CDCs that would have been deemed impossible a decade ago. Famicos Foundation, led by veteran director John Anoliefo, now serves Glenville after that area's CDC closed in 2015. Burton, Bell, Carr Inc. of Central now serves Buckeye-Shaker, where the long-troubled CDC recently failed to pay taxes on properties it owns and also failed to pass a clean audit test required by the city. Cross over to the west side and you have Old Brooklyn CDC collaborating with Metro West CDC; Tremont West Development Corporation and Ohio City Inc. partnering up on projects; and Detroit Shoreway providing community development services to Cudell through a shared service agreement.

Industry leaders say Cleveland CDCs, which have shrunk in number from more than 40 at their peak in the 1980s to fewer than 30 today, must combine resources to be more effective, and they're actively driving in this direction by tying funding to groups that work across neighborhood lines. For the past several years, the city and other funders have required CDCs to serve more than 15,000 residents, emphasizing collaboration and working together across neighborhood lines.

"There's a real effort to find ways to better serve parts of the city through partnership or capacity building that have not received strong services in the past," says Joel Ratner, president of Cleveland Neighborhood Progress (CNP), a nonprofit intermediary that provides support and technical assistance to CDCs.

Yet for Doyle, who is African-American, this mission is personal. He grew up in Glenville and watched its decline when he was younger, and now sees an opportunity to help guide development in a way that benefits eastside neighborhoods.

"The passion for the work for me is because I feel like I'm rebuilding home," he says.

CDC Changes

Cleveland's CDCs started off in the '70s and '80s as scrappy grassroots organizations that used aggressive organizing to bring attention to disinvestment, redlining and white flight in their neighborhoods. They were funded in part by the Commission on Catholic Community Action, which received support from the Catholic Diocese and the Gund Foundation. At the peak, there were literally hundreds of community organizers working across the city to improve neighborhoods.

That independent community organizing approach came to a screeching halt one weekend in spring 1982, however. At the time, Sohio, now BP, was headquartered here, and community leaders were angry at the company for making record profits at a time of soaring energy costs which were disproportionately borne by the poor and elderly, so they organized an action. Dozens of enraged community members "disrupted the annual SOHIO shareholders meeting, picketed at the home of SOHIO's president, and stormed the chairman's lunch at his tony suburban country club," according to "The Community Development System: Urban Politics and the Practice of Neighborhood Development in Two American Cities from the 1960s to the 1990s," a dissertation by Jordan Shein Yin presented to Cornell University in 2001.

This is relevant to today's CDCs because that's when many CDCs learned a painful lesson about not biting the hand that feeds them, and it's stuck with them ever since. The now-infamous "Hunt Club incident" didn't go over well with business and philanthropic leaders, to say the least, who immediately cut their funding. After that, CDCs shifted away from community organizing and toward bricks and mortar development, including work like building affordable housing, rehabbing older homes and helping businesses with storefront renovations.

The problem has always been that with many CDCs receiving the majority of their funding from HUD's Community Development Block Grants as well as their councilperson's ward allocation, these groups needed to please their elected officials in order to survive. While the best CDCs have developed a diversified revenue stream including development fees, fundraising and grants, many of them did not, and went under due to development deals that went bad in the recession. In the worst cases, CDCs in some neighborhoods have functioned as mini city halls that are effectively run by their council people, receiving as much support and funding, or as little, as that councilperson decides, which in turn is dependent on how involved they are, or what little or big dramas with CDC employees have preoccupied their attention.

Ratner, who has led efforts over the past decade toward adopting a community development model that goes beyond bricks and mortar to addressing racial equity, job creation and education, says that Cleveland's CDCs need to change. Too often, he says, the industry has been measured by how many CDCs there are rather than their effectiveness. In the past, all CDCs had access to similar funding from the city and their councilperson, regardless of how good they were at doing their jobs.

"We really want to keep our eye on the ball, and focus on quality community development services to neighborhoods, not just infrastructure," he says. "What we know is that too many CDCs for too long have not met the needs of their neighborhoods. What's the right number of CDCs? It's the number that can be sustained with the dollars we have and that are delivering effective services to their neighborhoods.

"Our job at CNP is to make sure that neighborhoods either maintain or improve the quality of community development service over time so that all neighborhoods ultimately — and this is aspirational, we're not there yet — have strong, transformational CDCs working there," he adds.

This is not exactly a new conversation. Some CDC leaders have long been frustrated with spreading CDC funding over all 36 of the city's neighborhoods. "What is the benefit to a neighborhood and the region if you have resources going to ineffective CDCs and equal or less resources going to effective CDCs?" Burton Bell Carr's Tim Tramble told Scene in 2015.

What's different now is that CNP has changed its funding criteria to promote collaboration, leading to many of the mergers, collaborations and partnerships that we're seeing today. Ratner acknowledges the challenges ahead, but he's bullish on the system, saying that even though there are fewer CDCs than there used to be, the ones that remain are more effective. Moreover, there's a renewed focus on equitable development that's different from the way things operated in the past, he says.

Ratner points to examples like new homes and businesses in the Circle North development on East 105th Street in Glenville, part of Mayor Jackson's neighborhood redevelopment plan. Scene reached out to the city requesting information on how the Department of Community Development awards funding to CDCs, but spokespeople did not respond to requests for comment.

"We feel that the system is stronger and more efficient than ever before," says Ratner. "We're delivering community transformation in many places, though there's still a lot of work to be done."

Out of the Ashes

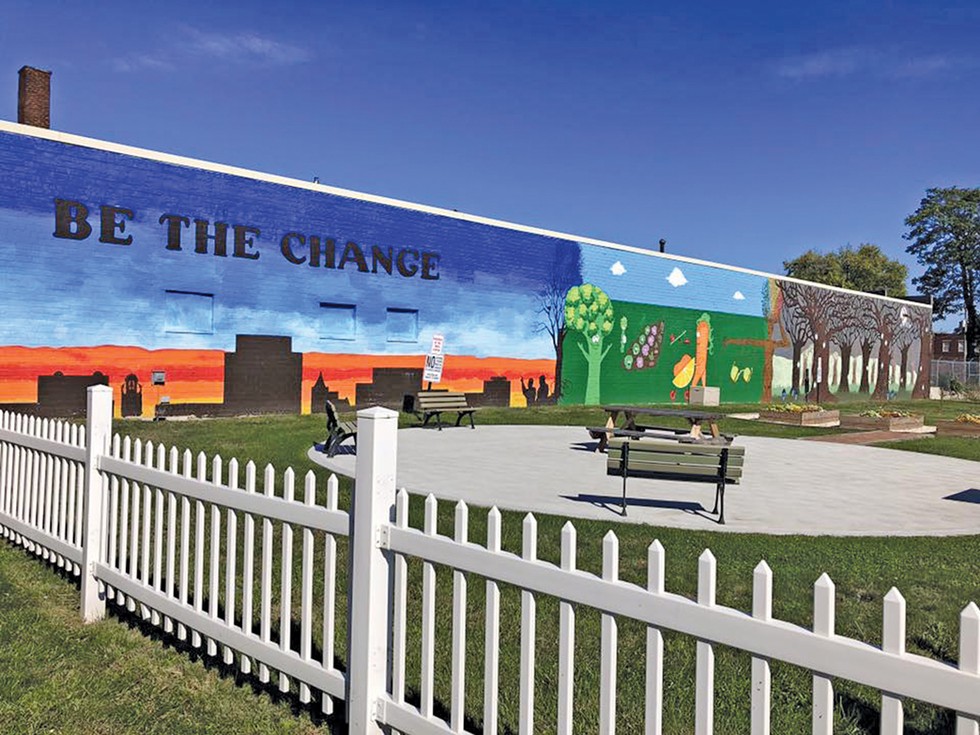

Doyle points to Greater Collinwood CDC's recent successes as evidence that the revamped approach can work. In the past few years, Greater Collinwood has worked with Cleveland Chain Reaction to bring nine new and rehabbed businesses to the area; secured a $50,000 grant for the initial re-vamping of the Five Points streetscape at East 152nd and St. Clair Avenue; saved Collinwood High School from closing and developed a plan to add programs there; and worked with Cleveland Metroparks' on the revitalization of Euclid Beach Park, a regional amenity that serves the entire city.

At the same time, he acknowledges the challenges and opportunities of a larger service area. For example, while Greater Collinwood CDC now serves more than 35,000 residents — "If we were a city, we'd be one of the 10 largest in the Northeast Ohio region," Doyle says — the organization has fewer staff members and less money than previous groups. Whereas there were once 22 staffers spread out among multiple organizations, today Greater Collinwood has just 12 full-time staff members.

"That's sometimes tough because we can't do everything we want to do," Doyle says.

Tim Tramble of BBC rattles off a list of similar challenges regarding serving an expanded area. He was initially reluctant to take over community development services in Buckeye-Shaker and, in fact, he and his board said no multiple times. "My main concern was to protect the integrity and efficacy of what we were already doing (in the Central neighborhood)," he says.

Nonetheless, they ultimately saw an opportunity to serve a part of the city that lacked high-quality services. He acknowledges that staffing a larger service area has made his job much harder. "The reality is, I'm only one person, and our associate director is only one person," says Tramble. "There's more work to do, and we have an inability to split ourselves into two people."

Nonetheless, he doesn't regret it. "We think that there is tremendous opportunity there, and that Buckeye-Shaker is a very special part of the city," he says. "There's a rich diversity of people who truly care about their neighborhoods. They all want the same thing, and there's an opportunity to forge a broader, more cohesive, more connected area."

Tramble, who is well-respected in the city for his success as leader of BBC, hasn't wasted time bringing his no-nonsense approach to Buckeye Shaker. Recently, BBC announced through a partnership with the city of Cleveland that it was acquiring the majority of buildings within a 14-block area of Buckeye between East 116th and East 130th Streets, in an effort to attract businesses and residents to the neighborhood.

Doyle says that organizations like Greater Collinwood and BBC could have a catalytic effect on the east side, where development has lagged behind. "The west side has received a disproportionate amount of funding and investment," he says. "Now, with organizations like Greater Collinwood, Famicos Foundation and Burton, Bell, Carr Development expanding their services, we're at scale. There's an opportunity to leverage the capacity of the east side."

Fresh Blood

Westside CDC leaders are also busy working together across boundaries. In Old Brooklyn, which has gained new coffee shops, restaurants and retail and where home prices have also gone up, CDC director Jeff Verespej has seen a sea change. In the past, CDCs were often focused on their own service areas to the detriment of collaboration, but that's starting to change.

"We've gone from everyone working just for the goals of their own neighborhoods to realizing we need to work with our neighbors," says Verespej, citing his ongoing collaboration with Metro West CDC on a healthy housing project as one example. Last month, the Cleveland Foundation awarded Old Brooklyn CDC a $99,000 grant to "help implement its health-focused strategic plan and strengthen the Benjamin Franklin Community Garden," according to an announcement.

"We're not going to succeed as a city if we have three places that are vibrant and the rest of our communities are still being left behind," Verespej says. "We've raised our game to make all of us better."

Other community development leaders in Cleveland share his optimism, though not without some hesitation. Jenny Spencer, managing director of Detroit Shoreway Community Development Organization (DSCDO), oversees neighborhood programs for one of the city's best-known CDCs. The organization has been serving the Cudell and Edgewater neighborhoods under a shared service agreement since Cudell Improvement Inc. lost its staff two years ago after years of what insiders characterized as mismanagement. The two groups are currently in talks about a merger.

Although working in a larger area can be challenging, serving a new neighborhood has allowed DSCDO to leverage staff expertise and heighten their impact. "Cudell and Edgewater share aspects and characteristics with Detroit Shoreway," she says of the organization's decision to start serving these areas. In the past, when staff members got calls or emails from residents or businesses past 85th Street, they couldn't help them. "It's always been an artificial boundary, with Lake and Detroit Avenues running through all three neighborhoods and connecting us."

It also allows organizations to tell a more powerful story to funders. Yet she cautions that it isn't easy and the two groups are still working on it. "I don't think there's been a successful merger yet," she says of Cleveland's CDC landscape. Residents in Bellaire-Puritas and West Park actually rejected a merger of their CDCs a couple of years ago. "At its core, it's about identity."

Doyle agrees that connecting North and South Collinwood is as much about neighborhood identity and class and racial barriers as it is about physical development.

Yet in the end, he says, having one CDC could allow residents and stakeholders to fulfill a long-held dream. "There has always been discussion that there should be one Collinwood, when in reality it's been over 100 years that Collinwood has been divided," he says. "There's an opportunity to reconnect the neighborhood in ways that it hasn't been. The community has so far embraced us and worked with us."