If you know someone with an urban planning degree, it's quite likely they have a line from the world's most overquoted words on planning in their email signature.

"Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistency. Remember that our sons and grandsons are going to do things that would stagger us. Let your watchword be order and your beacon beauty."

This is a Daniel Burnham joint. He's the godfather of planning, and he rightfully belongs to Chicago, where he grew up and which he designed. Like many of the post-Industrial Revolution titans whose names adorn our institutions, he did lots of other stuff across the nation, mostly neoclassical and Beaux-Arts-y endeavors — New York's Flatiron Building, Washington, D.C. (and Washington, D.C.'s Union Station), the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

But Clevelanders like to claim him too, for his involvement in our Group Plan (full title: "The Group Plan of the Public Buildings of the City of Cleveland"), the 1903 document that's the reason why our civic buildings are arranged the way they are — around downtown's central malls.

Our civic core is the most fully realized plan like this outside of Washington, D.C., and it's City Beautiful through and through: It embodies, perhaps a little too well, the beautification and monumental grandeur that planners around the turn of the 20th century sought as a reform to disharmonious social order through the physical embodiment of civic virtue. Mayor Tom Johnson made it happen.

The Group Plan might sound familiar, because its name was revived by the private parties that wrangled a redesigned Public Square into existence just as the Republican National Convention came to town in 2016. In between 1903 and 1916 and today, we've tried a whole bunch of big stuff just like this. Cleveland's history is littered with the souls of those who tried to remake it in their vision, and there are two useful texts in that vein.

Daniel Kerr's Derelict Paradise: Homelessness and Urban Development in Cleveland, Ohio details repeated attempts to build and rebuild a convention center; in that context, it's hard not to see the Global Center for Health and Innovation as a naked, pricey gamble. As was en vogue in mid-century America, city leaders solicited federal funding to rip out the "slums" that sprung up between downtown and the warehoused, working waterfront.

Mark Souther's Believing In Cleveland: Managing Decline In the 'Best Location In the Nation' will tell you how Cleveland obtained more urban renewal dollars than any other city to clear out what it deemed undesirable and replace it with the much more orderly, I.M. Pei-designed Erieview Plan. As people fled the city for whiter, wealthier suburbs in the 1970s, leaders engaged Lawrence Halprin, noted festival-marketplace planner, to reconstitute San Francisco's Ghiradelli Square in Cleveland to bring people back downtown with a conventional execution of walkable, manufactured, safe-seeming fun.

Charmingly, amid all this, an official of Dennis Kucinich's City Hall attempted to liven up the malls by putting out chairs for people to sit in during lunch, a refreshing attempt among all the bureaucratic emphasis on cataclysmic change that has fixed generations of civic leaders.

Today, we'd call this tactical urbanism. Also, today, we're watching a contemporary iteration of attempts toward cataclysmic change for purposes that aren't particularly clear beyond making Cleveland something that it certainly isn't: the unnecessary renovation of the Q, the laughably impossible Hyperloop, the absurd-sounding bid on a blockchain economy.

All this has us thinking about Cleveland's superlative imperative, its keen eye on success for a few, and our public unwillingness to look realistically at what's actually taking place. Like how, for example, 14,365 black residents left Cleveland between 2011 and 2016, and how black households earning more than $50,000 out-migrated at three-and-a-half times the rate of those making less. Or like how in 1960, 92.3 percent of residents worked in the city of Cleveland, but as of 2011, only 46.9 percent do.

Despite our legacy of big plans, data tells us that people are getting the hell out. No wonder Jon Pinney has been able to successfully commandeer a conversation about that ever-exhausting topic of civic leadership in Northeast Ohio. We've barely got a center here, and the center that we've got certainly isn't holding.

But we're pretty sure that the answer isn't more commissions, or more collaboration, or more City Club forums. To wrap our own heads around all this, we asked any architect with an office within Cleveland city limits — in case you're wondering, architecture firms cluster in downtown and Midtown, so take the advice contained herein on the city as a whole with as large a grain of Cargill-mined salt as you'd like — what they'd do with no constraints.

And by no constraints, we mean no budget slashing, no value engineering, and absolutely no political quandaries, all of which usually combine to stymie good ideas before they've had a chance to take off.

Those who responded to our inquiry floated design solutions that political insiders and plebes alike will recognize as variations on common themes: Our city is too divided; access to our waterfront, in a word, sucks; and we desperately need public spaces for our personal and social health. The designers and architects we talked to are a fantastically talented bunch, and gave us some incredible ideas — the thoughtful, deliberate kinds of ideas that can only come from a marrow-deep sense of responsibility toward and love for one's hometown. It's an honor to print them in our pages.

Without further ado, here's what we heard:

ALEX PESTA, CITY ARCHITECTURE

City Architecture's 25-year history has touched many a Cleveland neighborhood project: Hub 55, the West 25th Street Lofts, the West Shoreway. Alex Pesta leads City Architecture's planning practice, and offered what amounts to a modern reworking of some of the long-held equity planning principles put forth by the grandfather of the concept, Cleveland State's own Norm Krumholz:

"Focus and cluster investments in projects on Cleveland's east side with the sole focus of jump-starting development and raising land values to better balance Cleveland across the Cuyahoga; figure out how to pull Lake Erie's shoreline to the south — both metaphorically and, with creativity and aggression, physically; initial investments targeted and intended to narrow the equity gap as fast as possible must be done briskly but with a respect for heritage and cultural history/significance; once private development takes hold, and is determined to be authentic, subsidies should cease and city, county and other agencies need to get out of the way and let progress occur without cumbersome process."

Pesta says that the east side could be a model for "refocusing Cleveland's redevelopment aim" — a worthy moral undertaking that would extend far beyond a single project's physical reach. But it won't be easy. "Challenges, not the least is correcting decades of disinvestment and systematic racism, require leadership and steadfastness."

JILL AKINS, VAN AUKEN AKINS

Jill Akins leads Van Auken Akins, an architectural interior design firm with offices in Playhouse Square. The 25 employees at her 26-year-old firm have been on teams for the Hilton, the Global Center for Health and Innovation, and Hopkins International Airport.

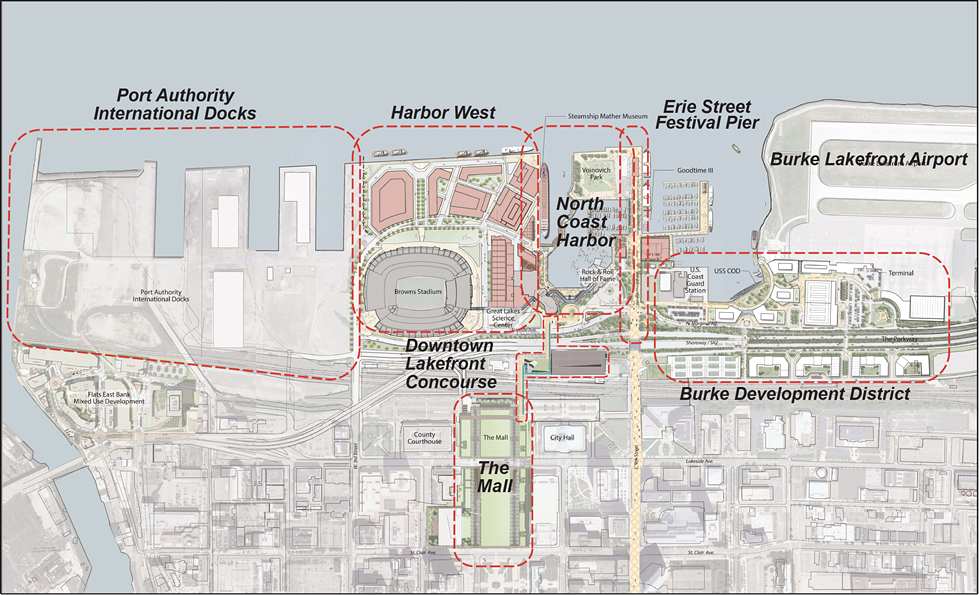

Akins endorses a plan that she and designers from Perkins Eastman collaborated on about four years back that tackles the silo-ing of the Browns stadium on the waterfront.

"That," she says, "was magnificent. I think so many people have been disappointed that the stadium is on the waterfront, but if you engage the stadium with retail and office, it would be fabulous. There's so much developable land north of the stadium, east and west, and we created neighborhoods — residential, commercial, and mixed-use. I think just starting with that and taking another hard look at financing it would be magical."

Perkins Eastman's plans for urban waterfronts loom large in many cities; the same firm is behind the cataclysmic development of Washington, D.C.'s Wharf, which has dramatically reshaped that city's southwest waterfront while providing a critical infusion of housing in a city that's strapped for it.

In addition to the "long process" that the two firms engaged in to create what she calls "a beautiful plan," Akins also worked on conceptualizations of how to get from the Global Center and the surrounding plazas to the waterfront. "That's really important, too," she says. "East Ninth is a wind tunnel, so we had a covered pedestrian bridge concept that could be heated or keep people dry in inclement weather."

"Our lakefront is so beautiful," she says, "and it's not being used."

MATT HILS, OHM ADVISORS

"No surprise: I would spend money on parks and public open spaces," says Matt Hils, a landscape architect with OHM Advisors. "There are a lot of great ideas out there currently, and there's no need to invent more." Hils says to double-down on the proposed Gordon Park expansion, the Irishtown Bend redevelopment, and neighborhood parks throughout the city generally.

"I'd like to distribute the wealth if you will, between downtown expenditure at Irishtown Bend and an eastside version of Edgewater Park, and spread the money out into the neighborhood so that there's a relatively equal distribution of public spaces for local neighborhoods. You need places for families to gather, reunions to take place, anything that's a memory-maker, anything that enhances family and community relationships. There's so much value to parks from that standpoint, the health standpoint, social and mental health — especially for kids." And for Gordon Park, in particular, which alongside a thoughtful reuse of the Cleveland Public Power site could be not just an eastside counterpart to Edgewater but perhaps even upstage it? "It should be a slice of a new neighborhood, a self-sustaining neighborhood with housing and commercial space that meets residents' and visitors' needs — it should be more than just open green space."

Hils pitches that every Clevelander should be within a 10-minute walk of green space, and notes that the city has already inventoried and assessed its 170 parks to prioritize their renovations. Each of those parks should have basic necessities: shelter, drinking water, heating, and places for kids to play.

"Anything that encourages engagement between people, anything that fosters interaction between different socioeconomic groups or races, anything that encourages integration of different social classes," he says, "because when you can get a wide variety of people together, that ultimately is where society is going to benefit from a greater understanding of people who are different from yourself."

RICHARD FLEISCHMAN, FLEISCHMAN + PARTNERS

Dick Fleischman has been dreaming big on this particular topic for, perhaps, most of his life. The founder of Richard Fleischman + Partners — which worked notably on the initial master plan for Gateway — was born and raised in Northeast Ohio. He spent formative years in New York and Rome, where he became convinced that Cleveland could be a crown jewel in a Riviera-like network of residential, recreational, and commercial areas along Lake Erie.

"What cities would you like to repeat?" he posed to us rhetorically. "Because the sunsets here are as good as anywhere in the whole world."

Fleischman has worked up two substantial documents. One is his vision for an Ohio Riviera — what he calls the Lake Erie necklace — from Toledo to Ashtabula, a "continuous urban concept" that would run along "unrestrained urban shoreline with continuous beachfront." The other is a collection of Fleischman + Partners' civic work, and civic dreams, created over the years, including the old Cuyahoga County administration building, 515 Euclid, Gateway Plaza, the Buckeye-Woodhill RTA, and a fanciful lakefront horse racetrack on top of a parking garage.

The introductory text to that second document says, "I invite you to rediscover the sense of space, the thing that puts the fire in your eyes. Within and around this issue, you can experience this most fantastic of voyages, the trip from your heart to your mind, from intuition to intention, from dream to reality. There is one destination: the quest to be. Every new generation should search for its own understanding of nature, man, art, and architecture through profound observations and reflections, and thus create a basis for their own creative activity. While the understanding of nature and esthetics are the key areas of philosophy, they are traditionally considered in historic terms, so we must look for our own ethics if we don't want to become guilty."

Which, in practice, means what? That we should do better than touting projects like East Fourth Street, which, while certainly important to the late-aughts downtown revitalization much-heralded by civic boosters, is, in Fleischman's words, "cute. A street of restaurants. That's not significant. That's cute." Instead, he asks, "What's going to happen in 2040? 2050? Whatever it is, it can't just happen by gravity. We have philosophers that talk about beauty and ideals. What happened to that?"

THEODORE FERRINGER, BIALOSKY CLEVELAND

Bialosky Cleveland has undertaken a number of projects that instantly feel well-loved upon their execution. Most notable is the new Edgewater Beach House, but Bialosky has also drawn out the charms of the Schofield Building; the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority headquarters; suburban hotspots Crocker Park and the emerging Van Aken District; and the yet-unbuilt Midway, which proposes center-running, physically protected bike lanes along the old streetcar corridors on Cleveland's radial arterials.

Fittingly, director of business development Theodore Ferringer, who led the initial conceptual planning for the Midway and is a board member of the Green Ribbon Coalition, sent us a response full of vim and wit that we couldn't bear to edit it down.

"The number one thing I would do is to build/implement the Cleveland Midway. The value proposition of this is so painfully clear. While many people at the city and other groups are working on pushing parts of the proposed network ahead, this project is still not receiving the prioritization it needs from both political and philanthropic leadership in Cleveland to happen as anything close to proposed on a reasonable timeline. In simple terms, the Midway is not a bike infrastructure project. It is an urban transit, streetscape, economic development, and social equity building project that increases Clevelanders access to jobs, school, each other, and green space that happens to provide, per every available metric, the best and safest urban cycling infrastructure possible.

"The second project I would do is the Green Ribbon Coalition's proposal to move I90 and reconnect Gordon Park with the lakefront. The long story short is that there is a once in a century opportunity to repair a key part of our lakefront. Since the closure of the First Energy coal power plant on the lake to reroute I90 and reconnect a massive area piece of otherwise junk real estate with the lakefront. The only reason I90 is routed where it is along the lake near East 72nd is due to the power plant being built first. Over 100 years ago the east side had a park every bit the equal to Edgewater — it is time to heal this scar and provide near east side Clevelanders a premier lakefront park. This isn't just a park — its an issue of environmental justice.

"After doing those two projects, I would then move onto finally following through the true vision of Daniel Burnham's Group Plan and connect Cleveland's downtown to the lakefront through a land bridge over the Shoreway as it passes through downtown. Bury a multimodal transit station for Amtrak, Greyhound (and other bus systems), and regional rail under the bridge and flank it with mixed towers a la Frank Gehry's never built downtown HQ tower for Progressive.

"After solving all that, I'd go back in the archives and cherry-pick from some of the proposals for this very thing from an exhibition I co-curated in 2009 with colleagues Jeremy Smith and Michael Abrahamson (of Fuck Yeah Brutalism fame and still the best idea ever hatched at the Happy Dog) called All You Can Eat: A Buffet of Architectural Ideas for Cleveland.

"Cleveland being Cleveland, we should probably be done with it and build LeBronze James. Since time is a flat circle, given that LeBron has now left a second time, we might be better off revisiting how we should have dealt with it the first time — bulldoze the whole place, making Cleveland a third-wave social network, and funding it all by selling our physical assets to the highest bidder and calling it Cleveland 3.1."

But can design alone heal us? Of course not!

Sure, we promised our sources a hypothetical situation that didn't involve constraints. But the realities of Cleveland — a continually flat or slightly declining population that results in an ever-weakening core, a region that favors greenfield sprawl, and a corps of elected officials that refuses to acknowledge any of this — necessitate an examination of external factors, and we don't mean the kind offered by talking-head technocrats when they themselves are asked to offer "big, bold ideas." So we pinged some experts in governance and environmental affairs to ask them to contextualize our built-environment fantasies.

One of those experts, if I may break from the royal Scene "we" I've been using thus far, is me. I'm a freelance writer, yes, but for a year and a half I managed UHBikes, Cuyahoga County's bikeshare network, which involved a nonstop effort to build up ridership, expand the system, and get Clevelanders to feel like they could get around their city via something other than a car.

I've worked in business development for global architecture and construction firms, and I've written at length for national publications — Slate, CityLab, Strong Towns, and the American Conservative — about the cultural and economic impacts of mega projects, planning decisions, transportation, access, equity and governance on Northeast Ohio's built environment. If my scattershot resume hasn't convinced you that I have some decent ideas about how cities work some of the time, might I also offer my half-finished master's degrees in historic preservation and public administration?

Free from the shackles of political and financal constraints, I'd echo Alex, Matt, and Theodore's insistence that public spaces are social, racial, and environmental justice concerns, and that the ones that we have should be far, far better. We should be using our pockets of green outside of downtown — which means getting away from all the focus on Public Square — for open forums, community engagement and just being outside. Per Jill's expertise, I'd find a way to responsibly engage our waterfront, hopefully in a way that respects all those great things that well-designed civic space can do.

All of this, of course, needs to occur in a city with a governance structure that works quite a bit differently than ours. Right now, we are helmed by a fourth-term mayor who seems a bit bored by his job and, on the ground, council members who view their jobs as providing constituent services rather than creating policy that could make Cleveland an easier place to live. A friend of mine, whose academic expertise is in the way that cities run themselves, describes this as "creating governance systems that exist along the paths people follow in their work, family, and social-life balance. Major employment centers, transit lines, day-care centers, grocery stores, health and human services, workforce development and local municipal offices have to match up in time and space to create true accessibility, community engagement, and economic mobility."

So I'd also tell Cleveland to think about design as passionately as Dick, whose decades of experience have led him to believe that a pursuit of beauty and truth will only come from a commitment to doing things seriously and deliberately. My ideals are a little bit less beautiful and a little bit romantic, but I don't think they're any less important.

To that end, I'd tear down highways, and I'd get the lead the hell out of our city. I'd run frequent, reliable buses north and south and east and west on our grid. I'd institute a public banking scheme that offered low-interest lending to bring homeownership within reach of more people, especially those who have been systemically locked out of the ability to build generational wealth through landholding, and offset the costs of caring for a property. I'd ban sprawl, because Cleveland and its inner-ring suburbs are now all losing population to the collar counties. This is to say nothing of topic areas that I know a little less about, but I think are equally important to decisions about building, planning and aesthetics: I'd institute a basic income. I'd extract hard-line community benefits from our nonprofit hospitals. I'd massively restructure our approach to law enforcement. And I'd throw as many resources as needed into our schools.

Another thing I don't know much about is the environment on which we actually build and plan and do all of the above. So I asked Christina Znidarsic, associate director of Chagrin Watershed Partners, to tell me more — not about buildings, but about what determines how and why we put them where we do.

CHRISTINA ZNIDARSIC, CHAGRIN WATERSHED PARTNERS

"I'm an environmental scientist by profession, and while I do spend time out in the field, I spend even more time working with local elected officials, zoning inspectors, planning directors, municipal engineers, and law directors because how communities choose to develop is one of the biggest factors in the health of our streams, rivers, and lakes. For me, being able to work with a community on review of their zoning and adoption of local regulations like compact and conservation development, riparian and wetland setbacks, and consideration of higher standards in their erosion and sediment control and stormwater management regulations is every bit as critical as completing a stream restoration project. Stream health and water quality are directly tied to the amount of impervious cover in a watershed, and it doesn't take much to tip the scale. The Center for Watershed Protection as far back as 2003 completed extensive research that shows streams begin to decline in health with as little as 10% impervious cover in their watershed, and after only 25% or more impervious cover they begin to fall into levels of impairment that cannot support healthy stream ecology.

"I want communities to understand that development doesn't have to occur at the expense of the environment; rather, it's far more cost-effective to protect the environment during development. Communities need to take a watershed-wide, regional approach to their planning, zoning, and development. Planning and policy that promotes sprawl means additional impervious surfaces creating more polluted runoff to already overtaxed storm infrastructure, causing expensive and destructive local flooding and stream erosion. Loss of natural greenspace, particularly forests, wetlands, and floodplains, to development means a loss of those ready-made, self-managing free storage areas for stormwater flow and requires costly infrastructure be built and maintained at the community's expense to restore that lost function. Protection of these natural flood-control areas through riparian and wetland setback zoning is a valuable, cost-effective tool local communities can use to help future-proof further development. It is common-sense zoning and should be as much of an accepted practice as side, front, and rear setbacks."

Phew.

We found it striking that amid a restless civic discourse about leadership; a growing acknowledgement that our public officials prefer the comfort of being steered by a business community rather than the risk-and-reward of actually undertaking governance; and the feverish promotion of not-terribly-smart stuff, those that we spoke to for this piece emphasized tangible, human-scale improvements to Cleveland that, frankly, should already exist.

Our waterfront is criminally under-used, our green space isn't super-fun to hang out in, and we crave neighborhoods within Cleveland's boundaries, not outside of them, that meet the needs of their residents first and visitors too. And all this exists within the wider scope of a painfully, continually segregated region that's long careened toward a grossly unsustainable future, aided and abetted by government policies, like single-family zoning that okays greenfield development, that most people deem too wonky to care about. Kerr's Derelict Paradise is a testament to Cleveland's continual ability to screw itself over in pursuit of a higher, fancier and more elite-friendly economy, but perhaps we've arrived at a breaking point.

While we were writing this, Cleveland celebrated its 222nd birthday. July 22 is Cleveland Day, as decreed by city council in 1906. That's the day that Moses Cleaveland pulled up to Settler's Landing, looked around and, in short, founded the city that we live in.

"The flats on the west side, and the densely wooded bluffs on the east, did not present a cheerful prospect for a city," wrote geologist Charles Whittlesey of Cleaveland's arrival in his 1867 Early History of Cleveland. "While the boat was being unloaded, the agent had an opportunity to mount the bluff, and scan the surrounding land. This view must have revived his enthusiasm, more than the swamps along the river had depressed it. A young growth of oaks, with low bushy tops, covered the ground. Beneath them were thrifty bushes, rooted in a lean, but dry and pleasant soil, highly favorable to the object in view. A smooth and even field sloped gently toward the lake, whose blue waters could be seen extended to the horizon. His imagination doubtless took a pardonable flight into the future, when a great commercial town should take the place of the stinted forest growth, which the northern tempests had nearly destroyed."

Whittlesey's superimposed ruminations of Cleaveland and his discovery party sound not unlike how our interviewees described the city, and its incredible potential. That's what makes these suggestions something we can stand behind. Daniel Burnham's edict to "make no little plans" doesn't even need to be considered. Instead, maybe a repeated insistence that all Clevelanders deserve the kind of access and quality of life promoted by the future imagined herein is simply doing the right thing.