Dude was ready to smoke some water. The five bucks he'd started off with in his pocket had already stretched into a day of low-key devilment, steady drinking and smoking. Now, as the November night outside sharpened into the mid-30s, he was ready to get high. Again.

For hours they'd been sitting around Puddin's house off East 131st Street near Kinsman, slapping playing cards around and drinking beer while her kids jumped around the house. There was Puddin, Maria, Nichole, Omar and Dude — who depending on the day or criminal charge might go by Clark Lamar or Clark Williams. On the street, though, they just called him Dude. The group had already passed around a blunt, finished off the Heineken that Dude and Omar had brought over, and killed the six-pack of Bud. Maria was talking about going to a party but it didn't start until midnight. In the meantime, Dude asked Nichole if she was interested in hunting down a wet square — a cigarette soaked in PCP.

They hopped inside her four-door Tempo, dropping off Maria before going on the run. Nichole called a dealer she knew named Hollywood to ask if he was dancing, code-speak for if he was holding PCP. He was, but Hollywood wasn't in the neighborhood yet. Give him 30 minutes. The Tempo rolled to a convenience store where Omar and Dude each bought a 24-ounce Colt 45 tallboy. Then they motored east, pulling off on Capitol Avenue, a quiet one-way ribbon of pavement linking East 93rd to East 86th.

Before the dealer could show, Dude spotted Nails, a guy he'd bought from before. He hopped out of the car, clunking his Timberlands over to Nails, then back to the car. Dude's pockets were empty, so he asked Nichole to borrow $20. She handed over the bill. Dude watched as Nails dipped the cigarette into the liquid, a mix of PCP cut with embalming fluid. He brought the square back to the car. The burning cigarette circled the vehicle.

The PCP did what it did, wrapping a bubble of distance around you, so much so that you weren't really you anymore but someone else, a character, a superhero even. If he thought about it, Dude had to admit — got nostalgic even — that the high wasn't the same as when he first started screwing around with PCP around 1985. He was now 30 years old. By his own rough count he'd spent half his life in and out of jail on felony charges. Honestly, the engine pushing all that criminal mischief was the search for the old high again.

Dude told Nichole he'd give her back her $20 if she dropped him back at his aunt's house up on Englewood, near where East 105th crosses St. Clair. They slipped into the driveway of the two-story house. Dude ducked inside to grab some money he had stashed. But as he was coming out of the house, a thought scurried out from under the weed, beer and PCP. He told Nichole, Hey, you smoked half of this cigarette with me, why don't I just give you back 10?

She started screaming, braiding together a mean rope of curses and accusations, shiesty and scandalous and ya'll fucked me up, talking pretty strong for a female, Dude would later tell people. Mid-tirade she flipped open her phone and began complaining to someone on the other end. Shortly after hanging up, Nichole switched up. "Fuck it, give me the 10 then."

They swapped the cash. Nichole zipped off. Omar and Dude tightened the grips on their tallboys and began walking up the street. But before they could step off Englewood, headlights splashed the road. Omar and Dude heard car doors flying open.

***

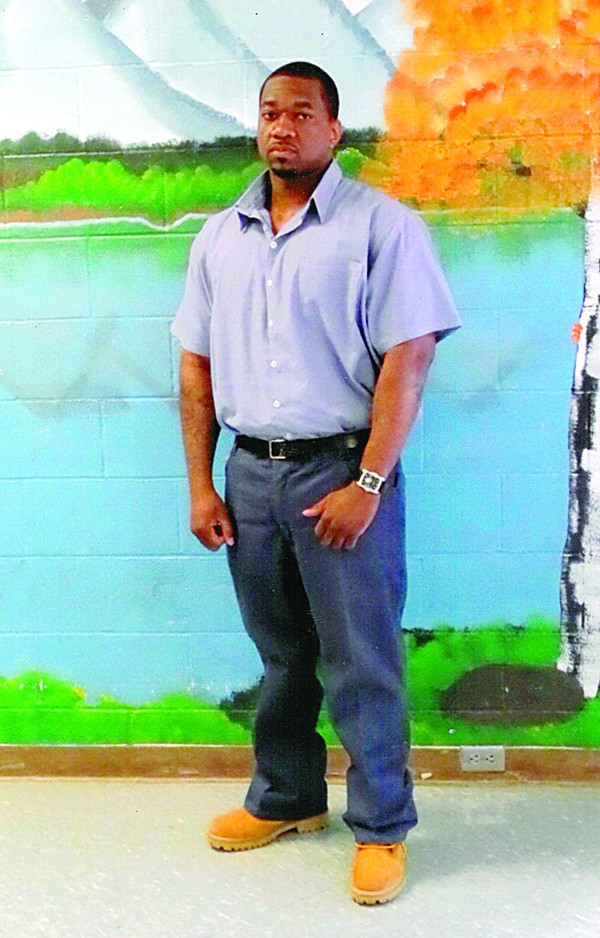

Thirteen years after that November night, Ru-El Sailor — El to his friends — sits in the visiting room at the Ohio State Penitentiary on the edge of Youngstown. He's dressed in navy-blue prison scrubs. His wide frame is bent over a table so low to the ground only preschoolers could possibly find it comfortable, but the staging is all the better to keep long-separated lovers from getting handsy. Washed-out fluorescent light showers down from above as visiting children wheel from the tables to the vending machines. El's hands rest on his knees, his face — dark eyes, tidy beard — looks relaxed, but there's a sick tint laid over his dark skin, like a jaundiced Instagram filter. He hasn't been out in the sun in more than a year.

"The only thing to do out there is throw a basketball around," he says with a shrug. "I want the next time I get fresh air to be when they are taking me back to county or when I'm leaving this place."

This place has been home since 2003, because on that November night in 2002, the beef over $10 for a PCP cigarette ended with the death of Omar Clark, blasted with 11 bullets on Englewood. Nichole Hubbard was arrested and tried for the crime, as well as her brother, Cordell Hubbard, and his best friend, Ru-El Sailor. All three were convicted.

"To be honest, I was naïve about it," Sailor says now. "I figured that if I didn't do anything, I might as well let the lawyers take care of it."

Since his arrest, Sailor has maintained his innocence, a claim that is seconded by Cordell Hubbard and bolstered by the bizarre way his May 2003 trial progressed. But in the end, Sailor scripted his own outcome, deciding to follow the bearings of a moral compass that was calibrated to higher standards than the world around him. His story reads like ghetto corner Shakespeare, where the best intentions boomerang back around, the fatal blow self-inflicted.

But the 2002 murder case also is a powerful example of how sometimes, in the American legal system, fact and the law wave goodbye to one another to veer off in different directions.

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 149 innocent individuals had their names cleared in 2015. That's the second record-setting year in a row for exonerations. The steady jump in those numbers tracks with a growing awareness outside the legal system about the failings of American justice, whether it's hashtags about the Black Lives Matter movement or the home run success of shows like Serial or Making a Murderer. More Americans seem to realize the courts screw up at a regular clip, a fact the legal world has been slow to admit. For all that, what Sailor's case ultimately highlights is how poorly the current system is wired to actually address innocence.

"Like I said," Sailor says, a blip of regret showing briefly in his dark eyes, "I was pretty naïve."

***

Everyone on the Four Block — that was what they called the neighborhood running from East 140th and St. Clair up to East 150th, a lattice of residential streets tucked south beneath I-90 on the northern lip of Cleveland's predominantly black eastside — knew El and Cordell went together like peanut butter and jelly. They were cohorts from the same streets, their lives and choices charting the same course.

El was the oldest, born to a single mother, Bernatte Brown. A nurse who juggled shifts working for an agency and as a private home health aid, she had to rely on El to take care of the others, Sharell and Duke, while she ground through double all-nighters. "He didn't give me too much trouble and he was caring," Brown says now. "When I worked nights, he helped raise the others, and I was happy about that. I could come home and everybody would be in bed, everybody was safe."

Sharell remembers her brother as a watchdog when tapped to babysit, never even letting her venture off the porch when he was boss at home. "He was also a horrible cook," she says today with a laugh. "If she had to work a double, when we came home she'd leave us pizza money. But he would keep the money and try to feed us something else like noodles. He would try and doctor them up but they'd just taste like a batch of salt."

A single mother with three growing kids is bound for some hard knocks. El recalls times growing up when the power company cut the lights over a past-due bill. Brown, an extremely proud woman, wouldn't ask for or take a handout to cover the expense; the family would just wait in the dark until the next paycheck came. The experience stamped El inside. "I was never going to let my kids go through that," he says now.

But on the Four Block, there weren't any handy maps to get out of that kind of economic crunch, except one.

"Social inequality" is the kind of blue-chip buzzword people like to staple to a situation like life in the Four Block, usually without going any further. But if you are trying to unwind the dug-in economic inequality in Cleveland, its origin story is arguably tied to years of intractable housing segregation. The racial partition of Cleveland's neighborhoods stretches back so far now it's baked into the city's DNA; but there is a good argument that much of Cleveland's social problems are bedded in the racial divisions of its neighborhoods.

In the late 1980s, Princeton sociologist Douglas Massey dug into census data and determined that certain metropolitan areas were not just segregated, but hypersegregated. Under the definition, these were metros where the black population is historically unevenly distributed through a region. Instead, the minority population is slotted tightly into a specific geographic area. Under Massey's rubric, Cleveland was one of the top hypersegregated cities in American.

Just last year, Massy published a report looking at whether hypersegregation still had a headlock on as many cities as it did 30 years ago. According to the 2010 census, the good news: Half the cities that had been hypersegregated back in the 1980s had shed the label, including Columbus and Cincinnati. The bad news: Cleveland is still hypersegregated. Unlike its Buckeye state brethren, Cleveland remains as racially bifurcated as ever.

Massy's argument is that the numbers game has serious, far-reaching consequences for people living here. Hypersegregation creates the kind of social and economic isolation that pools poverty and cuts off these parts of a city from the mainstream civic bloodstream, creating the harsh differences between locations separated by a 15-minute drive. Imagine the psychological blow of living close to the new buildings climbing into the Cleveland skyline in the Flats or downtown. Then imagine living on the boarded-up blocks deep on the east side that look like Sarajevo after Milosevic.

"People growing up in such an environment have little direct experience with the culture, norms and behaviors of the rest of American society," Massey wrote, going on to explain the irony that in a diverse and densely populated society such as the United States, some inner-city individuals "are among the most isolated people on earth."

The way this big-picture academic theory played out on Four Block, in Cleveland and in nearly every American urban core, is by creating a world apart but parallel to the American mainstream. For El, it was a simple breakdown. You were either in the streets, hustling, selling and using drugs; or you were in society, a citizen working a straight gig. It was one or the other. Red pill, blue pill. Different rulebooks. "If you're in society, and I do something to you and you call the police, I can't get mad at you," El explains. "That's what people in society do. But if you in the streets and call the police, then you're a snitch."

For El and the others coming up in the Four Block, there wasn't much appeal in the straight life.

"I always grew up fascinated by the streets," Sailor admits. "I wanted the nice things — the cars, the money, the clothes — and that inspired me to get into the street life. The people I saw who were working jobs were struggling. The people who don't and are on the street, they kick it. And it was super easy. If you grew up in the urban area, the most accessible thing you can get your hands on was drugs. Getting wasn't any problem."

For El, those two separate worlds were made all the more vivid by the two major male figures in his life: his father and his maternal grandfather. "I grew up with two role models, a positive and a negative," he explains. Sailor's father was in the streets selling drugs and working other hustles. His grandfather, James Brown, however, was a mechanic who could break down and build back up diesel engines with his bare hands. With his feet firmly in society, he preached to his grandson about staying honest and providing for his family and staying humble before the Lord. "He was the strongest man I've ever met," Sailor says ruefully.

El picked the streets, the nickel and dime bags, street-corner pharmacists, the cat-and-mouse routine with cops. By the early 2000s, he'd racked up arrests for possession, trafficking and a gun charge that landed him on probation.

But the undercurrent was different; something of society stuck on him, likely from his grandfather, the honest provider. "My father, he chose the street life over his children," Sharell explains. "Whereas my brother did the street life to help out my mother, to provide for us, to take care of his children. My father did it so he could look good and have friends and women. It was a big difference."

Cordell Hubbard was out there with El. They first met in fourth grade. From then on, they were never apart, including later on the Four Block's street corners. But more than the street game glued them together. Both El and Cordell were big music lovers, Cash Money and No Limit label staples, classics like Biggie and Tupac. They both were also stitched with entrepreneurial streaks gleaned from their fathers. In between his time on the streets, El's dad had tried his hand at various legit businesses — a fitness club, a restaurant — that failed to take. Cordell's father owned a market and some real estate. The two friends recognized the long odds on the streets weren't good. Guys got trapped there, rutted in the endless supply-and-demand hamster wheel. But others used their money as an elevator up to a higher financial perch by getting into real estate or opening a car lot or barbershop.

By fall 2002, El and Cordell were plotting their own such move into legitimacy, a step off the street back into society. They decided to open a music store — C and El's Music — in a space on East 116th and Martin Luther King Boulevard. They got their vendor's license and were prepping for opening. "We wanted to do something bigger," Sailor says, "instead of just selling drugs and being stuck."

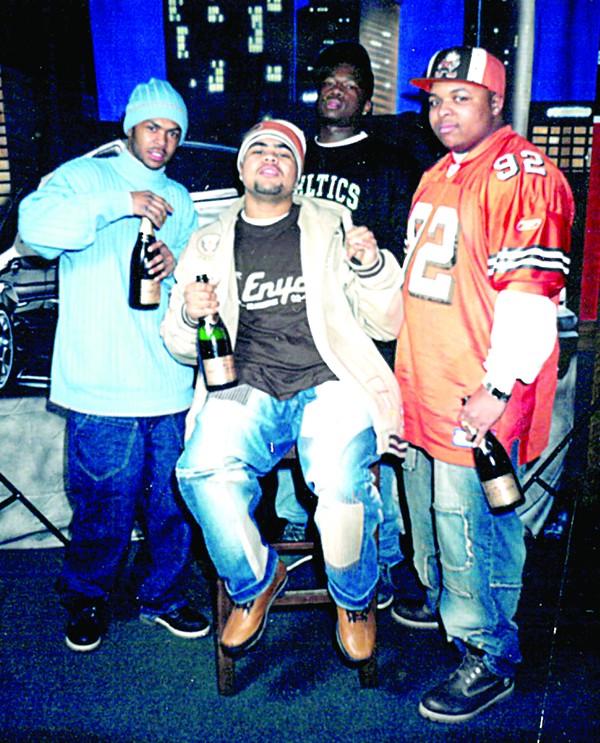

So there was a lot to celebrate — life shifts in the air — when El walked into the Benjamin's Bar on Nov. 16, 2002. Wearing a grey and red-trimmed New York Nets jersey and matching headband, he slid into a seat at a table with friends, hoisting drinks while watching Cordell try to rap on the open mic. Later the group went to another bar, then a party, picking up new company and dropping some as the night deepened, champagne and weed passing in the cars between stops.

By the end of the evening, Omar Clark was bleeding on Englewood, reading his own long odds on the faces of the growing crowd. "I'm not going to make it," the dying man said.

***

When the word "guilty" started rolling off the jury foreperson's lips, again and again and again and again, Sailor felt the hard smack of a reality check. His eyes, bugged out with insistent urge, swung on Cordell next to him at the defense table. He'd rode shotgun with his friend through this; now it was real. "You gotta let me out the car, man," Sailor said.

El got tangled up in the murder case late in the game. How and why is still an open question. But court testimony and records indicate that police attention had almost immediately fixed on the Hubbards in the aftermath of the murder: Cordell was indicted in December, Nichole in January. In an early interview with police, the latter claimed that during her fight with Dude over the $10, he'd pulled a gun on her, scaring her into calling Cordell for help.

In court, Sailor's lawyer alleged that police only learned about his association with Cordell in late March 2003, when Hubbard's lawyers filed a notice of alibi stating Ru-El Sailor was with Cordell at the time of the crime. Cleveland police detectives, however, testified in court they'd learned El's name in mid-February from a Sixth District vice detective named Eugene Jones, who had various run-ins with Sailor going back to his days at Collinwood High School.

Sailor learned police were looking for him in late April. He turned himself in. The Hubbards' trial was scheduled for May 19, and the date wasn't pushed back for the new defendant. Sailor's attorney barely had time to prepare. The judge also rejected motions to secure individual trials for the defendants.

The state's theory was that during her argument with Dude, Nichole Hubbard had called Cordell. Her brother came to the scene, where he verbally jarred with Dude and Omar. Sailor also came with Cordell and either was an onlooker or the actual shooter.

Two witnesses put Sailor at the scene. One, an Englewood resident named Larry Braxton, told the court he had been returning home with two friends on the night of the shooting when he noticed Omar Clark and Clark Lamar (Dude) arguing in the streets with two men. Omar tried to calm everyone down. "No, this is family, you all. This is family, calm down, chill out," Omar told the group before he was shot, according to Braxton. The witness later said he saw a stranger in a red jumpsuit pull a gun and shoot Omar. Braxton, as well as his two friends, initially described the shooter as a 5-foot-10, light-skinned black man in his 20s. The other two failed to pick Sailor, who is very dark-skinned, out of a photo lineup. Braxton, however, fingered Sailor as the shooter.

The other witness in the case, however, was the bombshell.

Dude — Clark Lamar or Clark Williams — made his first appearance in court on May 19, 2003, for an evidentiary hearing outside the presence of the jury. On the stand, Dude recounted the evening: beers, weed, card games at Puddin's, the hunt with Nichole and Omar for PCP. Dude told the court that when Nichole was raging at him for stiffing her on $10, she told him she was going to call her brother. After she sped off and the other car pulled up, Dude was accosted by a guy who demanded to know what they had done to his sister. Another guy, the driver of the car, produced a gun, according to Dude. This was the guy who killed Omar.

"Do you remember the other person that arrived with the person that's talking to you?"

"Do I remember him?" Dude responded at the hearing. "No."

But two days later, on May 21, 2003, Dude came to court with a different story. Despite failing to ID the shooter in the previous court hearing, now Dude said he could make the identification.

"I seen the killer," he told the court.

"Who are you referring to?" the prosecutor asked.

"The guy right there," Dude said, throwing a finger toward where Sailor sat at the defense table with Cordell and Nichole. "I recognized him in court the first day that I sat here."

"Are you presuming because he is at the defense table that he must be the shooter?" the prosecutor said.

"No," Dude answered.

Dude had already testified that he hadn't gotten a good look at the shooter. Also, his ID of Sailor ran counter to previous statements. After fleeing the scene, uniformed officers tracked Dude down at his aunt's house, where he reluctantly reported that the two men who had accosted him in the street — the man who yelled at him about his sister and the driver with the gun — were both light-skinned black men who could have been brothers. That account gelled with the initial accounts of Braxton and his two friends. Also, in the months between the shooting and trial (months Dude spent in jail on a probation violation), Dude was shown a photo array of the defendants. He picked out Cordell. He didn't pick out Sailor.