On one side were the boy's parents, who had proved they weren't up to the challenge. The boy's mother, Lois Deaver, was developmentally handicapped and living with an alleged wife-beater. Her husband, Cary Williamson, had lost custody of a child from a previous marriage -- in part, over allegations of sexual abuse, which he denies.

The other option was a capable foster couple, who had cared for the boy for the past 11 months. The couple taught the boy to sit up, crawl, and talk. They corrected his crossed eyes, kept him fed and clothed. Most important, they gave the boy the first stable home he'd ever known.

For Stucki, the choice was clear: The boy should go back to the abuser.

"With the slam of his hypocritical gavel, it was over," says foster parent Jim Carrington.

The decision may have had less to do with parenting than sexual orientation. Carrington and his fellow foster parent, Jerry Simler, are gay. And since being appointed to family court by then-Governor George Voinovich in 1993, Judge Stucki has made no secret of his distaste for gay parents. So much so that activists have begun to question whether he lets personal prejudice cloud judicial rulings.

"If you're gay or lesbian, with an issue in his court, you will not get a fair trial," says Eric Resnick, a writer for the Gay People's Chronicle who has covered Stucki.

Stucki first raised eyebrows in 1996, when it was revealed that Stark County's Department of Human Services was considering placing a child with a lesbian couple. State law prohibited discrimination against homosexual foster parents, explained DHS Director Donald Pond.

That didn't sit well with Stucki. Although the case wasn't on his docket, he nonetheless sounded off.

"I have a right to know where the children from my court are being placed," Stucki said at the time. "I'm reserving the right to discriminate on anything that goes against a child's best interests. These children have enough problems without putting them in that kind of environment."

Stucki went on to accuse the county of taking part in a homo conspiracy.

"Apparently, the Department of Human Services has had an aggressive policy for some time of recruiting homosexual couples to be foster parents," he said. "I had one of the attorneys, who was appointed by the court as the guardian of the child, come back and tell me he was introduced to mommy and mommy.

"If I have the legal authority, I will try to get those kids out of those kinds of situations," Stucki continued. "I'm the one wearing the robe, not the Department of Human Services."

Stucki's overheated rhetoric wasn't well received. John Hoffman, the judge to whom the case was assigned, recused himself, believing that Stucki's statements had compromised the court's integrity. "It left me at a level where I didn't feel comfortable," he says.

The lesbian women, who weren't identified in news stories, said they were outed because of some of the details reported about them. They blamed Stucki and sued him for invasion of privacy. Ultimately, the case was dismissed.

Years later, Stucki is more circumspect in matters of morality. He won't discuss the specifics of his cases with the media, preferring to play the role of victim.

"I naively thought that half of the people who come to my court would think I'm a genius and the other half would be unhappy," he says. "But in this court there really are no winners. We're dealing with heartache here."

Carrington and Simler never planned to have kids. Together since 1996, the two men had settled into a life of quiet domesticity, a family of two. All that changed in May 2002, when Stark County's Department of Jobs and Family Services came calling with an 11-month-old boy.

Cary Jr. came to the department's attention when his mother, Deaver, fled her husband, Williamson, and took the boy to a battered-women's shelter. She told a caseworker that Williamson "knocks me into reality" and sometimes put "his hands around my neck until I stop crying." (Williamson was never charged with domestic violence.) When Deaver decided to move back in with her abuser, the department intervened.

The abuse wasn't the only issue. The department learned that Williamson had once fed Cary Jr. scalding-hot oatmeal; rather than take the boy to a doctor, Deaver merely fed him cold milk. The accusations of sexual abuse against Williamson cinched the deal. (Deaver did not answer calls requesting comment; Williamson claimed that Family Services was out to get him, then hung up the phone.)

When the department went looking for a foster parent, Simler was the natural choice. The then-53-year-old was Deaver's cousin and the closest nearby relative who wasn't mentally handicapped.

At first, Simler wasn't thrilled about the addition to his home. But once he saw how quickly the child bonded with his partner -- then-36-year-old Carrington -- his fatherly instincts kicked in. Soon, he was doting on Cary Jr. as any proud parent would do.

Meanwhile, Williamson was taking mandatory classes to regain custody of Cary Jr. But he was hardly an eager pupil. He fell asleep during an educational film and skipped anger-management sessions. A psychological evaluation found him "unstable with a ruthless indifference for the welfare of others."

So when Simler filed for permanent custody of Cary Jr. in March of 2003, social workers thought he was a shoo-in. They were stunned when Stucki awarded custody to Williamson and Deaver.

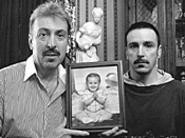

Two years later, the split-level house that Carringon and Simler share in Perry Township still feels too big. Pewter angels sit on shelves next to old pictures of Cary Jr.

The men take bitter comfort in knowing that Deaver kicked Williamson out of the house and that he hasn't seen his son in six months. "But she'd take him back in a second," Carrington says despairingly.

If she doesn't, Williamson plans to sue Deaver for custody when the divorce is finalized later this month. Once again, Stucki will be called upon to decide the child's fate.

It would seem a no-brainer. But Judge Stucki is full of surprises.