“Tonight a lot of people are hearing the words ‘participatory budgeting’ for the first time, and City Council would like you to join them in their scarcity mindset and believe that jobs will be lost and nothing will improve.”

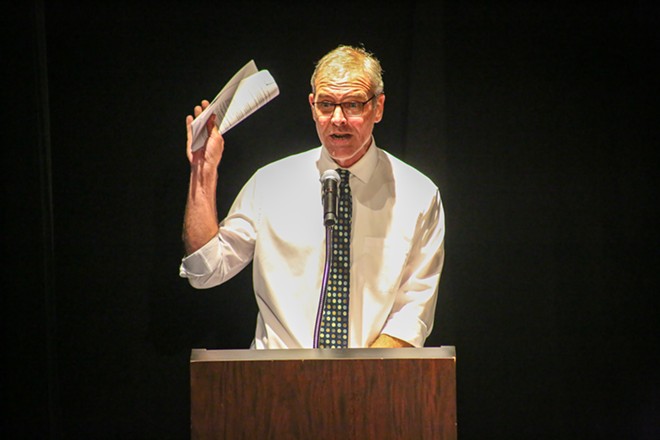

Starks joined fellow People’s Budget Cleveland (PB CLE) petition committee member Jonathan Welle to square off against director of Programming and Community Partnership at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History Robyn Kaltenbach and vocal PB CLE critic councilman Kris Harsh in a debate over Issue 38, the proposed charter amendment that would bring participatory budgeting to Cleveland for the first time.

If voters pass the amendment on November 7, it will take several years to go into full effect. By the fourth year after its adoption, though, residents would have power to propose and vote on how to spend an amount equivalent to two percent of the previous year’s General Fund. In 2023, that would mean $14 million.

While Starks and Welle accused Council of protecting and enforcing a status quo that neglects Clevelanders, Kaltenbach and Harsh derided PB CLE as impractical and unaffordable. Throughout the sometimes raucous debate, attendees didn’t hesitate to make their voices heard, too, cheering, booing and sometimes shouting from the audience.

“Their job tonight is to defend the status quo,” Welle said. “They want you to believe that this is as good as it gets…Residents are the experts in their neighborhoods. Residents are what keep this city going and every day, all over this city, residents are fighting for a bigger vision for what our city should be.”

But Harsh and Kaltenbach pushed back hard, arguing that PB CLE would siphon urgently needed money from city services, usher in unprecedented corruption and benefit only a select few.

“Their entire case rests on emotional appeal,” Harsh said. “They hope that you’re going to be so enraged you’ll vote for this disastrous hand-out to their friends, but that doesn’t mean that I’m going to mortgage your future to make a handful of activists happy.”

Although both Council and Bibb oppose the charter amendment, they will be responsible for selecting the members of the 11-person steering committee outlined in the legislation if it passes, not PB CLE. But regardless of who selects members, Council has characterized the committee as a “shadow government,” which won’t be subject to the same legal scrutiny as elected officials.

“The people do not control this money. The steering committee does,” said Harsh. “We cannot forget that…The committee of ten part-time people as young as 16 and one full-time staffer are going to be the ones writing the contracts. Remember, the committee oversees the fund so they have complete control over who they write contracts for. They can decertify ideas however they want.”

Kaltenbach warned that participatory budgeting would be “another special interest for the well-connected,” echoing Harsh’s repeated criticism of PB CLE as a “privileged people’s budget” that only a small pool of well-to-do Clevelanders will have the bandwidth to care about.

Starks took explicit issue with that argument. "This is pretty clear race-baiting. Harsh wants low-income Black people to believe there's no way Issue 38 could benefit them,” she said. “Do you think Kris Harsh understands how it feels to be a low-income Black person in Cleveland, and can speak for them?"

The teams also sparred over issues of corruption and election security. According to the proposed amendment, “since residents themselves approve this spending,” contracts for winning PB CLE projects would not require approval from the city council or the mayor.

“With $14 million on the table and no oversight, it will be open season for shady actors looking for an easy buck,” said Kaltenbach.

Because all city residents aged 13 years and older would be eligible to vote in PB CLE elections regardless of criminal record and immigration status, not all voters would be registered. As a result, Kaltenbach raised concerns of ballot stuffing, voter fraud, bribery and intimidation.

“This has been done throughout many cities throughout the country and I’m sure that Cleveland can figure it out just as other cities have. We shouldn’t be focused on a scarcity mindset,” Starks said.

For underaged voters, Starks proposed facilitating elections through schools or parents. Solutions to protect elections from fraud were less concrete, though Welle noted that PB CLE could work with experienced consultants who have successfully implemented participatory budgeting in other cities to balance access and security.

The amendment emphasizes involving young people in the democratic process. Those as young as 13 years old can vote, and the minimum age to serve on the steering committee is 16 years old. Although it says the mayor and the city council should “strive to appoint residents who represent the diversity of Cleveland regarding age, gender, race, geography, LGBTQ+ status and socioeconomic status,” the legislation also stipulates that they “shall prioritize the participation of residents under the age of 30 and members of historically marginalized communities.”

Welle defended the clause, arguing the importance of involving those “traditionally left out,” but admitted legality would have to be determined by lawyers.

Starks and Welle also took shots at what PB CLE has called undemocratic attacks on participatory budgeting, including Cirino’s Bill 158, mail sent by Council President Blaine Griffin to Ward Six residents opposing Issue 38 and legislation sponsored by Griffin to use public money to support or oppose ballot issues–which was dropped before it was introduced in Council.

“We’ve had this problem with the state legislature for decades. They’ve always been interfering in our affairs in the city and that is not a new issue for any of us,” Harsh said of the bill, maintaining that Council has the right to educate voters on issues affecting the city.

Unsurprisingly, rhetoric repeatedly turned to affordability–an issue PB CLE has struggled to sell. Nearly 30 percent of Cleveland residents live in poverty, and those aligned against PB CLE say that $14 million appropriated through participatory budgeting would be a massive hit to the city.

“Why do you think that your neighbors aren’t smart enough to decide how to spend public money in their own neighborhood?” said Starks.

In the past, PB CLE organizers have cited the city’s capital spending as a potential funding source besides the General Fund. Cleveland’s “Capital Budget” sells bonds to fund projects, but opponents say it's not a feasible way to supplement the General Fund.

“The city sells bonds to pay for capital improvement. There’s not a pot of money called the Capital Budget that they can just dip into,” said Kaltenbach. “If that were bonded every year, the debt alone would be $6 million, making the whole project about $20 million a year.”

Ahead of the debate, PB CLE posted a series of infographics on social media with other potential funding sources, including “Council’s casino slush fund,” projected tax revenue from legal cannabis sales and more. Starks and Welle brought their message that “it’s time to stop subsidizing billionaires” into the debate with calls for “stadiums over people.”

Ultimately, PB CLE pivoted from financing and contended that the fight comes down to power, not money.

In January, with the support of Bibb and councilwomen Gray, Howse, Maurer and Spencer, PB CLE approached Council requesting $510,000 in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) money to establish a participatory budgeting system in Cleveland. If it had been successful, it was planned to allocate $5 million more from ARPA through participatory budgeting.

“Let’s be clear: it wasn’t about the money…City Council opposed this on principle,” said Welle. “They don’t want to share power with residents. They don’t think that residents deserve to make decisions about how taxpayer money gets spent in their neighborhoods.”

Unsurprisingly, Harsh disagreed. He said PB CLE came “with a hand grenade and acted shocked when City Council insisted on protecting the people who elected us.”

It’s unclear if or how the debate will impact Cleveland in November’s election. Although both sides’ campaigns continue, Cirino is fast-tracking his bill, which would prohibit residents from voting on the appropriation of public money and render Issue 38 unlawful and unenforceable.

If the voters do get a say on the amendment, PB CLE faces plenty of opposition. While it has allies like Cleveland Votes, NAACP Cleveland and Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, the coalition has been denounced by a slew of major unions in Cleveland.

“Unfortunately, because of the tight timeline, I think that City Council members who oppose it got to those folks first and I think there’s low information on the reality of what projects get funded, and unfortunately for too long I think a lot of public sector unions have had to go to the negotiation table with a scarcity mindset out of fear…that they won’t get funded,” said PB CLE campaign manager Molly Martin at the Columbus hearing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter