After three hours of canvassing the wilds of Train Avenue as part of the regional RiverSweep day cleanup efforts around the Cuyahoga River corridor in May, I heaved two final garbage bags into the back of an overflowing trailer to join their distended brethren, bulging with soiled clothing, diapers, cardboard, used condoms and plastics of every shape, size, and function produced — judging by the labels of fast food wrappers for long abandoned menu items — during the past decade.

Two other trailers made laps from east to west and back, joined by two industrial Republic services garbage trucks, collecting regenerating mountains of bags as the volunteers — some 75 adults and 75 students participating in service days — ventured off below bridges, over railroad tracks and into the weed-forested hillsides to pick up trash with double-gloved hands, piles evaporating and being replaced within minutes. Larger items — your appliances, old box TVs, construction debris, tires, furniture, mattresses, shopping carts, scrap metal — waited on the side of the road beneath signs posted at regular intervals reading: "DUMPING IS ILLEGAL; VIOLATORS WILL BE PROSECUTED."

In all, 12 tons of garbage would be collected that day along Train, in addition to some 250 tires.

Peeling off both layers of gloves — a latex set on the bottom, outdoor workman gloves on top, standard issue from the organizers once you signed a waiver — I felt that yes, there was an absurd amount of garbage that was physical evidence supporting the 2.5-mile street's reputation as Cleveland's most notorious dumping ground, but if this was basically what had accumulated since last year's RiverSweep, save for anything already scooped up that had been blocking traffic, it was better than I had expected.

My naivete was almost immediately corrected.

How'd you guys fare out there, a burly man straight out of Sons of Anarchy central casting asked after getting out of the truck and introducing himself — Jeff Goforth, a volunteer who regularly works with Dave Reuse at the Metro West Community Development Corporation.

Not bad, I replied.

Yeah, we let it go for a couple of weeks since you guys were coming down, he said.

Huh?

Yeah, we're down here basically every Sunday filling up two trailers, so we skipped a couple of weeks.

Reuse, a former cop whose title at Metro West is Greenspace and Graffiti Coordinator, essentially a modern-day Sisyphus tasked not with a boulder but with trash, elaborated a few weeks later.

Metro West services Clark-Fulton, the Stockyards and Brooklyn Centre, areas in which dumping by individuals, contractors and companies has long existed at plague-like levels.

"Our service area is from West 25th to about Denison and West 90th, and it's a lot, between alleys and vacant lots," he said. "One year, I dropped off a truckload and a guy said, 'Congratulations, you're over a million.' A million what, I asked. 'A million pounds of garbage for the year.'"

That's just one anecdote of the endless supply he's got primed and ready from 10 years on the job, and many more before that organizing RiverSweep since it started 30 years ago, to paint a picture for anyone uninitiated to the grim, dangerous hamster-wheel world of dumping.

Another...

"I got a call one day that 47th Place was blocked," Reuse said. "It was about 2 p.m. We go down there and clear it. My buddy calls after that and says, 'You a bit lazy today there, pal?' What do you mean? '47th Place. You haven't gotten to it yet today.' I told him we just left there, it's cleared. He laughed. 'Well then it's blocked again.' It was 4:30."

But, for all that Reuse deals with — "I had to pull my gun on a guy one time at 56th and Denison. I was videotaping him dumping, he picked up a 2x4 and came after me." — it is the topic of Train Avenue that immediately saddles his voice with frustration and exasperation.

"We went down there the Sunday [after Riversweep] and cleaned up again," he said both after and before a sigh. "And I went back a couple of days later and there were six or seven piles."

He will call the city occasionally for cleanups of grander scales, but both because the response time isn't exactly swift and because of the regularity with which garbage is deposited, it's simply easier for him to deal with it himself.

Enforcement against illegal dumping is sparse, prosecutions rare. The Cleveland police department is short staffed, and calls for dumping are among the lowest in priority, meaning someone might show up to take a report six hours after a call. Unless you spot a license plate, good luck tracking down the offender, especially when folks obscure or remove plates before unloading a dump truck, quickly and while still moving, and exiting within minutes. With only three working cameras to deploy in targeted enforcement zones, Train's largely ignored in favor of more residential areas. The street — dark, largely uninhabited, equal parts industrial and vacant except for the far western tip — is not only an easy target but doesn't have hordes of angry residents banging on the doors of City Hall for a remedy. In fact, it doesn't seem like the city cares at all.

"That's putting it politely," Reuse said.

Which is probably true, and would also be true of every previous administration, which is how we got to where we are.

* * *

THE HISTORY

Train Avenue has existed for 150 years essentially as it exists now — a location for Clevelanders to dump garbage and through which to move quickly between the handful of neighborhoods it connects.

It sits atop, and in other parts parallel to, what was once Walworth Run, a tributary of the Cuyahoga River whose origins were near West 65th St. and Clark Ave. and whose endpoint was three miles to the northeast. While the Cuyahoga has long been the dividing line between the east and west sides of Cleveland, it was Walworth Run that was considered the boundary between the town's two sides in the 19th century and formed the southern border of Ohio City before the city was annexed by Cleveland in 1854.

Historical accounts say the "bucolic" slice of nature that served as an open space for residents along the "pastoral channel" was, like many other waterways at the time, a casualty of booming industry and population. In other words: pollution.

From Historical Cleveland:

"Culverts and bridges built over it by the city on occasion collapsed, or were washed away in storms, spilling stones, iron, and other materials into it. Slaughterhouses, breweries and oil refineries, which located along the Run near the Big Four railroad tracks, used it as an open sewer for their industrial waste. Residents did much the same, dumping down the hillsides and into the Run everything from table scraps to ashes to tin cans to broken glass. To alleviate flooding in the Isle of Cuba — that west side Czech community located just south of the Run — the City built storm sewers that channeled rain water into it. Eventually, the Walworth Run became so swollen and polluted that, by the early 1870s, nearby residents, whose lands had by this time been annexed to the City of Cleveland, were clamoring for City Hall to do something about it."

In exquisitely appropriate Cleveland fashion, it took two more decades of complaints, and court battles, before the city did anything, finally ceding to resident protest by 1897 and finding the money necessary to construct a sewer completely enclosing Walworth Run, a monumental engineering feat completed in 1903.

Following the "transformation of the picturesque brook into a foul-smelling, litter-clogged dank body of water," the combined sewer — 16 feet in diameter, wide enough for a train to pass through — alleviated many of the issues, and still operates today. With a divider separating sewage from stormwater, the former originally heading to Lake Erie before the advent of sewage treatment facilities and the latter being directed into the river, excessive rainfall brought a new if lesser problem when the two commingled over the barrier and millions of gallons of untreated sewage flowed into the Cuyahoga.

Today, heavy rainfall brings an average of 43 annual discharges from the Walworth Run sewer into the river, pouring some 330 million gallons of overflow into water, levels exacerbated over time because Walworth Run's original watershed of 2,125 acres has become a sewershed of 4,355 acres thanks to development and impervious manmade structures.

As part of the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District's Project Clean Lake — a $3 billion, 25-year program to abide by a federal consent decree to reduce sewage overflow — the Westerly Tunnel is under construction to alleviate pressure on the Walworth Run combined sewer. NEORSD estimates the new system will reduce overflow from 330 million gallons a year to just 15 million.

* * *

THE GARBAGE

Once the sewer system was installed, a road called Walworth Ave. was paved, parts of it eventually being abandoned, and parts of it being renamed Train Ave., with the remaining section of Walworth running from West 44th St. west, jutting north around Menlo Park and parallel to I-90 before turning southeast again and terminating out at West 65th.

As for how early Train became Cleveland's Trash Avenue, as the Cleveland Press dubbed it in 1980, the answer is both clear and not. Scant historical record detailing dumping or trash on the street exists in the PD or Press archives before the 1940s. With the number of businesses and residential homes located on the stretch in the early 1900s, it's likely that the sewer and freshly paved street ushered in an era of, if not pristine neighborhood living, something approaching it for awhile, but it doesn't appear to have lasted long.

A 1943 Plain Dealer article relayed the cleanup plans of area middle schoolers along the entire east to west run. "The appearance of Train Avenue in the neighborhood of the school has been bothering the children ever since the scrap drive last fall when the area was found to be a fertile source of metal," it read. "Children in the neighborhood are fearful of the multitude of rats which are attracted by the litter dumped in many places along the high bank."

Litter progressed to heavy dumping in the next two decades. A Cleveland Press article in 1966 detailed the plight of car-strippers with a photo capturing two burned-out autos, one overturned, with the caption: "The bridge under West 41st St. also is a popular haven for car-strippers who apparently had enough time to do a thorough job on these autos without interruption from police, or anyone else."

By then, today's familiar refrain was already being sung: "Dumping is forbidden by city law, as posted frequently along the street," the Press noted. "Area businessmen are sympathetic to the problems police face in catching the culprits. To do so would require full-time surveillance. An almost predictable timetable is followed by the car strippers. Cars are driven, pushed or towed to the sites each weekend [on Train Ave.]. They are stripped of every removable part. The shells are left. City crews are called in. By the next weekend the area is almost cleared. And it begins again."

A Press photo from May 10, 1978 captured what a mudslide might look like were it carrying trash, spilling down a hill and literally pouring out into the road. "The once scenic stretch of road now bears a closer resemblance to a junk heap," the caption read, noting that the Cleveland Service Department promised it would be abated.

Following up two weeks later, the Press quoted the city's waste commissioner saying the area had been cleaned but that "he doubted the area would stay clean since it is a favorite spot for illegal dumping."

As you know, it did not stay clean, with the Press's designation of Trash Avenue following in 1980, which preceded an impassioned if doomed streak of attention from city officials. Then service director Joseph Stamps called for a limit on private trash haulers to only operate in daylight hours. There were calls for the police to once and finally give the road more attention and a letter to the editor in the Press from then Ward 5 councilman Lester McFadden lambasting then mayor George Voinovich.

"All my efforts to solve the problem have been futile," McFadden wrote. "The mayor toured Ward 5 on Oct. 2 and Train Avenue was shown to him. On at least two occasions, priority efforts in my ward were submitted to the mayor's office with Train Avenue high on the list. It is a shame and disgrace that residents using Train Avenue to go to and from downtown must be subjected to this eyesore. It is also a shame that the residents and business places on Train Avenue have to live with this mess."

And, yes, dear reader, live with it they did. The frequency of stories and headlines ebbing and flowing as the street became, and then was abandoned as, a hobby horse in various years by local newsrooms, but always coming around to an undeniable fact — nothing had changed. It was forgotten and ignored.

A 1987 Plain Dealer column relayed the sad tale of residents who called over the course of an entire week for police to deal with a car that on day one had been stolen and dumped, by day three had been stripped, and by day seven had been burned. "It's not still there, is it?" a police spokesperson told the reporter more than a week after, promising to get a crew out there when the answer proved to be yes.

Tom Benedict, one of just two members of the Cleveland police department's litter detail in 1991, basically shrugged his shoulders when telling the PD what an overmatched battle he and his colleague faced throughout the city. Suffering under the same difficulties faced by police before them, all of 257 citations were issued the entire year with just 18 arrests. A slight improvement on Train was noted, with Benedict giving credit to the efforts of the local redevelopment association and groups who "had picked the area clean by hand."

Which is essentially how it's been for decades — ineffective official enforcement when there's enforcement, general decline, and yearly cleanups by volunteers and nearby residents to fill the void, because they care, and because few others seem to. It's a sentiment no better summed up than by Louis Zelazo, a retired and disabled truck driver who lived off Clark and West 54th in 1976 who, while talking to the Plain Dealer about a cleanup effort he organized on Train near the site of a murder that year, said, "The ultimate goal I'd like to see is everyone going out and trying to save their neighborhood," he said. "I've lived in this neighborhood all my life and I don't want to move to Parma. I want to live here."

* * *

THE BODIES

On Aug. 20, 2018, a security guard called 911 and told dispatchers a resident in his complex named Michael Thompson wanted to speak to police. He could not tell them why.

When they arrived, Thompson, a 64-year-old former truck driver suffering from an undisclosed illness, told them that twenty years ago he had killed a prostitute and buried her body off Train Ave. and Richner Ave. just east of West 41st St.

Investigators from the FBI and the Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner's Office joined police as Thompson led them to the shallow grave.

If the ever-present detritus is the most common visible sign of minor crime on Train, the bodies are the more infrequent yet serious reminders of the gruesome history of the street.

It was almost exactly four years earlier to the day when the body of 31-year-old Michaela Diemer was recovered from a field near the same intersection in August of 2014. Ronald Hillman, a 47-year-old who worked with Diemer at Progressive Field through Minutemen staffing, had raped and murdered her before dumping her body. After her family had filed a missing persons report, someone spotted Hillman, who was on parole from a previous rape conviction, driving her car. He confessed to the crime and directed police to the body before they even completed the drive downtown after picking him up.

While in those cases suspects have been caught and sentenced to life in prison, the case of Christine Shook remains open with a reward offered by Crime Stoppers. Shook, a 23-year-old dancer who worked at a bar on Clark, was discovered dead, wearing only a black jacket and white socks, near the tracks on Train on Jan 4, 1990 by some children who were collecting cans.

The coroner reported she died from blows from a blunt object to her head, chest, and extremities — in other words, a vicious, grisly full-body beating — and that she had been dead for more than a week before being found.

And where there were memorials and remembrances in modern cases, there was that plus vociferous outrage and mobilized protest in 1976 after one of the city's most brutal and unsettling murders. It's a case that has evaporated into the backpages of Cleveland's memory, but it's one that at the time struck a citywide nerve, even during a decade as bloody and tumultuous as the bombing era of 1970s Cleveland.

On a Saturday in late June 1976, the body of a young girl was found behind a vacant building that was once part of Standard Brewing's mini empire between 58th and 61st on Train Ave. Once a humming cog in one of Cleveland's last independent brewery operations of that era, the building had been abandoned, though technically owned by a local wrecking and excavation company, and was the scene of vandalism, drug deals, drug use and enough untoward behavior that neighbors had long lobbied for intervention from the city.

The body was quickly identified as that of 8-year-old Karen Kollar, who lived with her family on West 47th St.

Police said, "she was thrown from the roof of the three-story brick building and landed on a canopy over tracks of an unused railroad spur," according to the Plain Dealer report that week. "Her body was then thrown again from the canopy to the ground where she was bludgeoned on the head with stone slabs."

Four suspects, three of whom were neighbors of the Kollars, were arrested the following week — Dallas Stuckey, 19; Guy Frehmeyer, 18; and David Zytowieki, 21; and Susan Zytowieki, 16.

Kollar, police said, met her untimely and gruesome fate, after telling David that his young wife had missed an appointment with her juvenile court probation officer. The foursome, in retribution, kidnapped the girl and brutally beat her to death.

Picketers lined the street in front of the scene of the crime for weeks after, loosely organized as the Brewery Group, collecting signatures for a petition to have the building torn down and soliciting donations for her family.

Then councilwoman Mary Rose Oakar and Mayor Perk's office resisted, hoping instead to find a new tenant for the building to inject business into the deserted stretch. The Plain Dealer's editorial board sided with officials, cautioning residents and picketers to "exercise patience," but lamented that city inspectors repeatedly ignored their complaints until belatedly citing the owner for failing to secure the building.

"While this action is welcome," the PD wrote the Tuesday after the murder in June 1976, "it is nothing short of disgraceful that it did not come sooner, that it had to be prompted by one of the most vicious crimes in the city's history. Where were the inspectors prior to Karen's death? The condition of the building was common knowledge in the neighborhood. City Hall, too, should have been aware of the building's condition. Not very long ago it was proposed there that the city lease and use the vacant structure for a manpower training center."

Indeed, in June of 1975, Cleveland City Council's finance committee tabled plans to use the building after discovering it was, to put it lightly, unsuitable.

"It looks like a bomb hit it," then councilman Dennis Kucinich said while asking for the city's building department to do a full inspection of the building.

That did not happen until a year later, days after Kollar was killed.

If the common threads aren't readily apparent, they should be: vacant and abandoned homes and buildings, vicious assaults and rapes where the victim is a usually a young woman, oftentimes defenseless, oftentimes of lesser means, oftentimes working on the fringes of the economy and society.

And outrage that flares up and inevitably settles down as the cycle repeats. Because nothing has changed over the decades on the street, essentially. Every era has its blaring headline news of dead woman, and dead bodies tied to drug deals, with the occasional bizarre deaths — like the weekend of the "West Side Sniper," who killed one on Storer Ave. and shot another on Train Ave. in 1984 but was never caught — or bizarre blotter item, like the man who left two bags of heroin and cocaine worth $2 million on the side of Train that same year — dropped in between the dumping, arsons, robberies and prostitution arrests that have clogged Cleveland police dispatch logs on the street since... well, forever. It's a familiar, notorious and common nexus point.

As a retired local cop said in the book Cleveland Cops: The Real Stories They Tell Each Other, while remembering a robbery on the near west side and their pursuit of the perpetrators: "We drove down Train Ave. because we figured that was the route the robbers would take. We get on, and the robbers go flying by us."

* * *

THE DOGS

Local filmmaker Jeff Theman was adding another tattoo to his collection from Sean Kelly one day in 2014 when Kelly started talking about dead dogs.

He'd found them, more than one, quite a few in fact, on Train Ave.

"[Sean's] an artist, and he lives close to Train, so he'd walk down there, he was telling me," Theman said. "He'd try to find things to reclaim for his artwork, or just walking his dogs, and one day he just stumbled on this bag, opened it, and it was a dead dog."

"There's just so much garbage down there," Kelly said. "Your curiosity gets piqued and you want to know what's in those bags."

Theman, who directed Guilty Till Proven Innocent, a documentary on breed specific dog legislation, was immediately interested and looking for his next project, so he soon went down to wander Train with Kelly, filming for a possible movie.

"We started going out together and one day we found three bags in one day," he said. "Just one day. We found two that were fresh and one that was just bones."

Each had a passion for dogs and the pairing spun off two artistic projects on the topic.

Kelly, after calling the APL numerous times upon discovering dead canines — along with, he said, dead goats and dead roosters — got frustrated with what he thought was a lack of compassion and action on their part.

"I'd call the humane investigator and then feel like I was getting the run-around," he said. "They were dumped right there at Train and Wiley, right in their backyard, and I felt like I wasn't being taken seriously. I had asked them to put up cameras at certain spots where I was consistently finding dogs and I wasn't getting any help."

He also wanted a modicum of proper decency for the deceased pups — more than 20 in all, he estimates — many of which were clearly abused. So he'd take them to get cremated, which is all the APL would be doing anyway, if the city didn't find them first and simply toss them in the landfill.

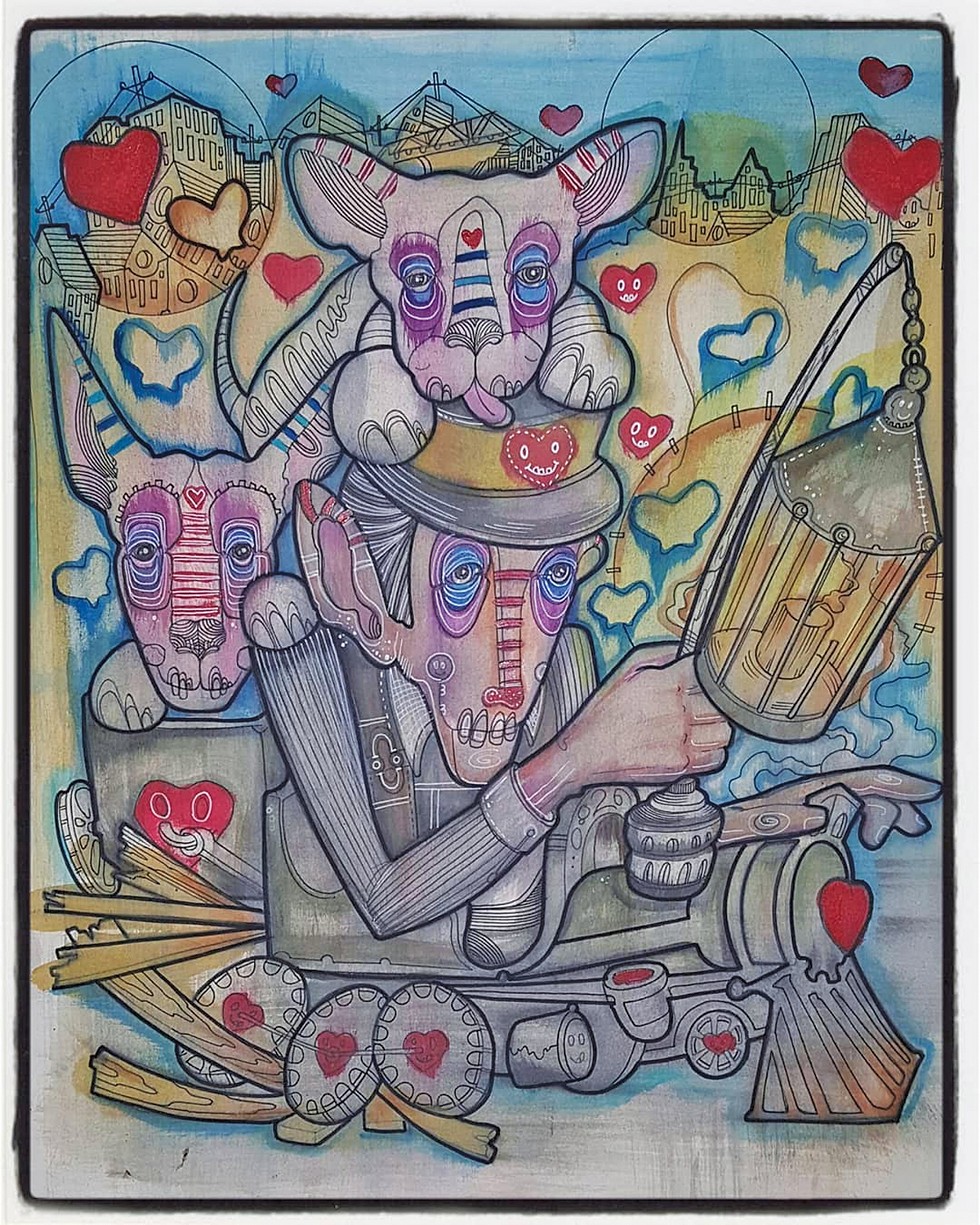

At some point, Kelly started incorporating the dogs' cremated ashes into his paintings.

"My first thing, it wasn't art," Kelly said. "It was first, you find a dead dog, and you cry. You sit and cry. I would just cry for a long time. It wasn't about the art. It was about how can I give them one last bout of respect and compassion. That's why I'd have them cremated. Some of the skeletal remains I had made into a box, a little way of paying respect to them."

And it wasn't all about campaigning against the abuse of dogs in underground dogfighting rings, which is and has been an ongoing issue in Northeast Ohio, as a Plain Dealer story detailed in Sept. 2018. A vice detective on the beat for five years told the paper it was a growing problem and that Train Avenue had become a regular spot for disposing of dead pitbulls because the street was "a dumping ground for everything."

Kelly was certainly aware of that, but "the thing is people get real pissed off about the dogs, but they instantly go to one place — these people are abusing dogs," he said. "That's definitely happening, but at the same time people go down and bury their dogs because they don't know what else to do or they lack the resources. A lot of people don't know what to do, and in that particular area... it's not an affluent area."

At the same time, Theman had put together a trailer for his next project, which he debuted alongside Kelly's art at the Derek Hess Gallery in 2018 in an exhibition titled The Dogs of Train Avenue. The most recent, updated trailer was released in early July and Theman hopes to have the full film released later this year.

"Every big city has a Train Avenue," Theman said. "I just don't accept we can't do anything. And for people in the city, either they know about Train Avenue [for the garbage] or they don't know about it all. It's like the city's given up."

"I was told by people that eventually it'll be cleaned up," Kelly said, "but it doesn't stop unless you take some steps. I had always said I didn't want to find a dead body down there. I've been down there at 2 in the morning [in the area] where [Michaela Diemer's] body was found dumped, and I always thought that's one of the places they should put cameras. You can come up from above and go back down and go up and leave and no one knows the wiser. We can't have that. It's a dirty street, but the thing is it's a good street."

* * *

THE ART

One of the reasons Kelly and others believe it's a good street is for one of the reasons that a casual observer, and the local CDC, might believe it's in bad shape: the graffiti.

On RiverSweep day in May, I watched as a volunteer opened the back of a van, handing out gallons of paint and rollers to an awaiting mob of high schoolers on the edge of the tracks thrilled to have lucked out with the task of painting cement walls rather than scavenging for rusted metal or rotting refuse on nearby hillsides, ravines and under bridges.

The graffiti remediation portion of RiverSweep paled in scope compared to the garbage collection — 30 gallons of paint were used along all 10 service areas, including Train Ave., according to Canalway Partners — and the targets along Train were simply the most visible ones. But to consider graffiti on cement pillars beneath bridges and on the side of the embankments of a train track worthy or necessary of remediation is confusing to those who know, practice and appreciate graffiti art. (That would include councilman Matt Zone, who proudly told Scene he and his 1980s-era breakdancing group, Project V, would tag along Train.)

It's art. Perhaps not the art you like. But it's art. And Train represents one of the broadest and most popular canvasses of the past 40 years.

"It's like a museum that's open to the public, essentially 24/7, to view, and if you're in-the-know, you can go whenever you want," said Bob Peck, a Cleveland artist who ran down the abridged history of tagging on the street for Scene.

It began with the Fun Wall on 27th and Queen, just around the corner from, in terms of notable modern day landmarks, Porco Lounge and Tiki Room.

"The Fun Wall was an abandoned building that had been torn down and just the foundation walls were left," Peck said. "You had enough space — about 100 yards on one wall, 50 yards on the back — and people started painting there in the '90s. By the late '90s, what essentially happened, was it got too overcrowded and sort of touristy. So the whole Train Avenue thing kind of spun off from that, as people started looking around down the hill and around the corner for someone to go and that connected and led to other locations." (The Fun Wall would evolve into a DIY skateboarding park with supporters bringing in commercial cement until it was eventually completely torn down four or five years ago.)

Graffiti's ever-evolving, ever-updating, ever-adding, self-policed, self-curated gallery world exists under a set of unwritten but nevertheless semi-codified rules.

"The biggest thing is, like every other graffiti destination, is to have respect for it," Peck, who during his time on Train had his brushes with packs of wild dogs, junkies, and an encounter with a man who claimed to have been the one to burn the building down that became the Fun Wall, said. "A lot of people have this misconception that graffiti artists don't have respect. And a lot of people don't understand the culture, or can't read the words, and don't get it. But most graffiti artists aren't going to write on a church or a car. At the same time I've seen people go down there with a can of spray paint and think it's just a free-for-all. No. You take your spot, and you paint only where you know you can. There are various rules and regulations, like one that if you can't burn it, don't paint over it. Basically, if you're not good enough to do better than the piece that's already there, leave it alone. Or if it's a memorial, or one of an artist's last works."

And the graffiti on Train, in terms of concerned remediation, which he believes is centered on its reputation as vandalism and a lack of appreciation for the art, doesn't make a whole lot of sense to him.

"From what I know working with public arts groups and neighborhoods in the last decade, they are more concerned when someone's got a point to prove or trying to make a name for themselves, grabbing a can of black and writing their name on every storefront for a block," he said. "And there's also this thing where people think it's just vagrants or ignorant kids running around. 'Why aren't these people in art school?' Well, a lot of them are, and a lot of them have real art jobs. They just have a passion for the culture."

And when the culture disappears, as it does from time to time with gallons of paint on cleanup days or in preparation efforts prior to the arrival of large-scale events in Cleveland, history gets lost.

"[When things get painted over] it sucks," Peck said. "When they had the RNC and went down the RTA lines and graded out a long stretch of the west side, we lost decades of history, stuff we can never get back. Even commuters afterward were in disbelief, saying they couldn't believe they did that and now there are just gray walls. The Train thing is funny, because there's a school [Menlo Park Academy, off Walworth Ave.] where there was a bunch of graffiti and when they made it a school they kept a lot of it — inside, on conference room doors — and the kids love it. That's cool shit, and they learn a little about the culture."

* * *

THE FUTURE

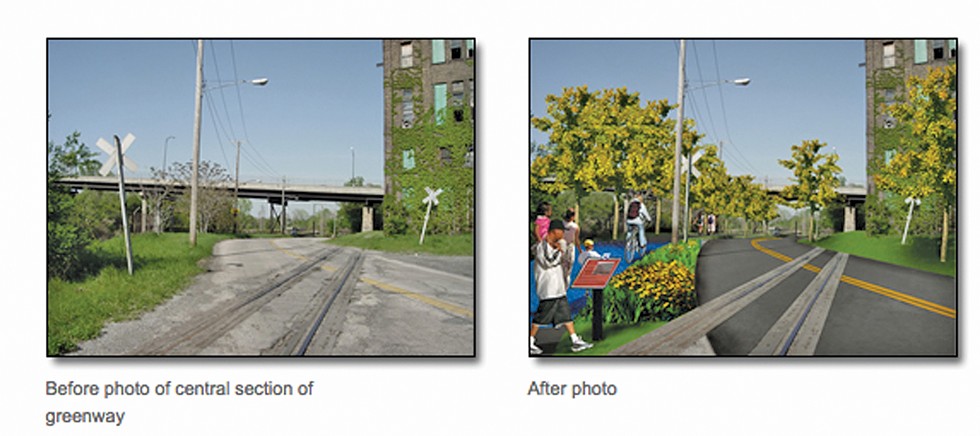

A little more than a decade ago, the city of Cleveland, along with the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency and Cuyahoga County, completed a study examining the feasibility of making Train Avenue a greenway. The proposed multi-purpose trail along the road would connect the Zone rec center with the Towpath Trail on Scranton.

This pie-in-the-sky dream made a certain amount of sense at the time in 2008, as the city adopted a Master Bike Plan in 2007 and set its sights, in theory, on transportation planning geared toward bikers and pedestrians.

The goals, laid out in the presentation, were to improve the aesthetics of the street, re-establish Train as a "community asset," promote alternative transportation methods, and to improve connections between neighborhoods and other bike paths.

In other ways, of course, it didn't make sense. This was the year after the financial collapse, and whatever early appetite for redevelopment of west side neighborhoods that had been growing had stalled. Plus, construction of the greenway, including the necessary trailhead land acquisition, was estimated at some $3.4 million, and other projects over the past ten years — the Red Line Greenway, the Lorain Avenue Bikeway — gathered official and private support, along with funding.

The Train Avenue Greenway is still listed on the city's Master Bike Plan, but what could be a "funky urban parkway with great views of bridges," as then Stockyard Redevelopment Organization Executive Director Al Brazynetz told the Plain Press while community meetings were going on in 2008, something like the Dequindre Cut in Detroit or the Grand Rounds Scenic Bikeway in Minneapolis, remains a pipe dream. One that some, like Matt Zone, whose district includes a tiny slice of Train and who was part of the 2008 feasibility study, think would be nice but far, far down the line.

(The city of Cleveland, naturally, did not respond to requests for interviews on the topic.)

The challenge, as the study laid out, in transforming "what is now a sewer and dumping ground into a parkway" involves not only the makeup of the stretch — 48% industrial, 43% green or open space, 9% residential — but the fact that those numbers haven't changed much.

But that's exactly the reason some folks think there is hope, folks like former councilman Joe Cimperman, who was also part of the study.

"I wonder how soon after this story developers will start talking about the street again," he said.

Perhaps, because as development in Detroit Shoreway and Ohio City pushes south past Bridge to Lorain and beyond, and development from MetroHealth and in Clark-Fulton pushes north toward Lorain, and development in Tremont continues to max out, there are few open options left to fill in, Train being one of them.

The City Planning Commission seems to know this and has prepared zoning in advance to help test the waters and draw interested parties. Two years ago sections of Train around the Fairmount Creamery apartment complex near Willey and Train, whose construction and tenancy showed there was demand in the area, were upzoned from industrial to semi-industrial, a designation that allows residential units, and the maximum building heights were elevated to either 115 feet or 175 feet tall, depending on the plot.

* * *

THE PRESENT

Human beings are disgusting. And lazy. And cheap. Which is a recipe that, on a stretch of pockmarked asphalt two and a half miles long with no one really paying attention, has proven unbeatable for a century.

Dumping is a problem in other areas, and has been throughout Cleveland's history, thanks to Cleveland-level city services, cratering economic decades, garbage strikes, shifting populations and neighborhood evolution. Some Cleveland Press and Plain Dealer archive stories detailing garbage woes of eras past include photos that could not be mistaken as anything else but landfills but instead are patches of vacant lots, oftentimes mere blocks from huge apartment buildings or nestled in otherwise thriving communities, where residents and contractors have deposited tons, and tons, of trash.

But Train remains the undefeated champion, in pure volume and years.

Cleveland police Sgt. Andy Ezzo, also the officer in charge of the Cuyahoga County Environmental Task Force, was not available for an interview but did respond to some questions in writing through a spokesperson on the topic.

"Dumping on Train is not different than any other area according to law," he said. "We investigate a dumping case on Train Ave. as if it were any other location. We collect evidence, look for cameras to collect video and check for witnesses." But, "one of our most difficult issues on Train is the inability to mount cameras. Our cameras use batteries for power and since Train is such a highly driven street, the camera batteries would run down too quickly."

"Dumping affects a whole community," he said. "It is something no one wants to see, as it promotes future dumping and leads to infestations of rodents and insects. Dumping is a felony that carries a 2 to 4-year sentence and/or a $10,000 to $25,000 fine. However, without the assistance of the community, it makes it very difficult to get results. Witnesses can call 216-664-DUMP or 311 when they locate a dump. However, if they see it occurring, they should call 911 and report it immediately."

Reuse understands Ezzo's predicament. After all, they're fighting the same battle with the same bad odds, watching the same piles build up by dump trucks trying to undercut the competition by skipping a trip to the dump where fees can run $50 to $60 a pound and instead depositing their contents for free on Train.

"I've been fighting for more cameras for years," Reuse said. "They only have three now, and they move from place to place, and one time when they put a camera off Denison it was damaged so badly it was completely broken. I give people my number, because dispatch takes too long. I'll call the commander directly.

And when people are caught, like a guy who'd dumped dozens of times before finally being identified, Reuse feels like they get off light.

"He was sentenced to a whole bunch of community service hours," Reuse said. "He didn't serve them. We followed his case. He didn't serve his hours."

And not everyone wants to be a Good Samaritan.

"You need to permit police to do the job," Reuse said. "Get more police, so you're not running from call to call to call, because these are not high priority, and you're not going to have time to look for a dumper. They can encourage people to be witnesses, but a lot of times people don't want retaliation, so it's, 'I didn't see nothing.'"

They found four dead dogs on cleanup day in May, and they must have been freshly dumped, because Reuse said they hadn't been there just the day before.

One or two years prior, however, he found a live one.

He'd seen the dog over the course of the three months, he said, here and there along Train, circling back to the same spots once Reuse started leaving food out for it. But he hadn't seen it for a couple of days.

On cleanup day someone called him and said there was a dead dog on a mattress. He didn't think anything of it — this was common, after all — so he went out with his truck, prepared to scoop up the carcass. But the dog moved as he got closer.

"It was completely infested with maggots, its whole body" Reuse said. "She was alive, but barely."

He took her to Gateway Animal Clinic where his girlfriend worked. It needed a lot of help, but they slowly nursed her back to health with the financial assistance of the Dick Goddard Foundation, the legendary local weatherman's nonprofit that helps rehab abused animals and fund low-cost care.

Eventually the dog returned to health and was adopted, one of the few happy stories Reuse has in those stuffed memory banks, and one that gets him choked up years later.

"We named her RiverSweep," he said.