With the numbers of uninsured in Cuyahoga County still increasing, Scene probed what it takes for the uninsured to get care — and what it ultimately costs.

My rule on seeking medical attention is no more complicated than this: If it doesn't require an ambulance, I will put it off until such time as I can fit it neatly into my scattered schedule. But this time I've gone too far.

A while back I walked into the protruding branch of a blue spruce tree. Over the days that followed, my vision grew fuzzy — though not fuzzy enough for me to do anything about it. But now the blurriness has progressed to a point that an explanatory "I can't see" creeps into nearly every conversation I have. Every time I get in my car, a little voice nags that driving is not a good idea.

The time for action had come, and the moment seemed right to tackle everything at once; I haven't had an annual physical exam since the Clinton Administration and am adept at ignoring the hereditary bone disease I will almost certainly develop.

And I have insurance. But what if I were one of the nearly quarter-million Cuyahoga County residents without?

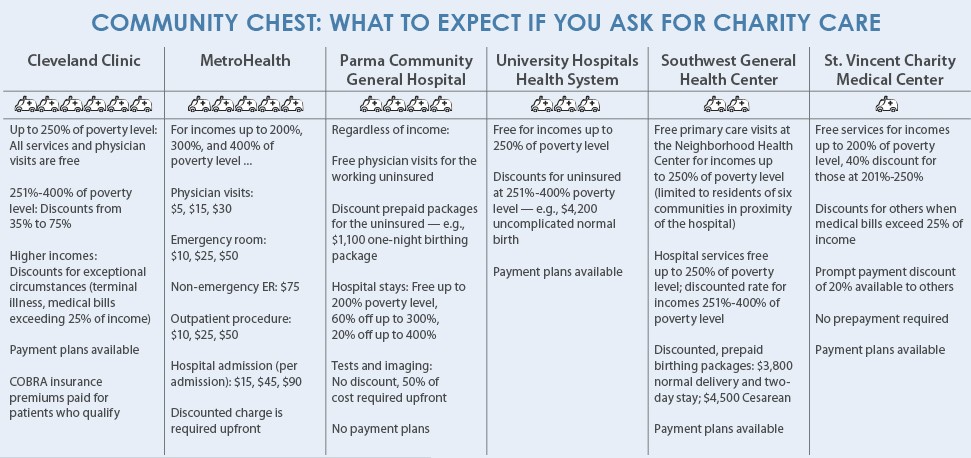

At the beginning of the year, Cleveland Clinic announced plans to rein in charity care at the same time University Hospitals Health System revealed its intention to expand it. What does it all mean, and what does it take to actually get help?

In a sometimes quixotic quest for answers, I posed as an uninsured part-time worker making about three times the poverty level. Armed with nothing more than my real-life ailments, I put the big competing systems — the Clinic and University Hospitals — through their charity care paces. Also included: Parma Community General Hospital, one of three remaining independent hospitals in the county (the others are Southwest General Medical Center in Middleburg Heights and St. Vincent Charity in Cleveland).

The results are encouraging. If you are single and earn less than $43,320 or a family of four making under $88,200 (that's 400 percent of the federal poverty level, a typical cutoff point for care), there is help. There are even substantial discounts for the uninsured who make more than that.

"Most people don't realize there is assistance, or that they qualify for help," says Sharon Giuliani, Parma Hospital's director of patient access. Despite rumors of an improving economy and expanding job market, she says, the number of uninsured asking for help continues to rise.

The downside of seeking that help: You will need a tremendous chunk of time to search for the best deal. And those big Cleveland Clinic ads promising same-day appointments? Unless you lead a small yet prosperous Asian nation, those appointments are not going to happen for you.

Invasion of the

Financial Counselors

It seemed a sensible move to seek out the same Clinic specialist who tends to my mother's bone disease. I called the appointment line but ... no insurance? No appointment. I was told I would first need an ominous-sounding "financial review." A counselor would call within two days. But four days passed, and I spent them worried about the interrogation that surely awaited. Would I need tax statements and pay stubs? Would this be worse than closing on a mortgage?

When I finally connected with the counselor and told her which doctor I wanted to see, she offered up a pre-programmed response: "That will be $519 for a first-time visit and that won't include him actually doing anything. How do you want to pay — credit card?"

Before I could recover enough to respond, I heard, "Wait! Were you referred by another physician? If you were, then it will be $663."

Now in shock, I managed an emphatic but high-pitched Why? Evidently, the doctor who doesn't actually do anything for $519 requires $144 more if he has to put a call in to the referring doctor.

I had mistakenly assumed that the entire purpose of this financial review was to determine my ability to pay, but at no time was I offered information on whether I might qualify for a discount based on my income. Good thing I asked: I did qualify for a discount — 75 percent off — but I would have to pay half the full amount upfront in order to be granted an appointment. My discount would be applied "after the fact."

This was a problem. I knew that this doctor was popular — six-month waits to see him are common. Forking over hundreds for the privilege of scheduling an appointment that won't happen till summer?!

Thus began my charity care odyssey.

During that first review, I was dismayed to learn that each Clinic department and facility is assigned a separate financial counselor. Naturally, the regular doctor I had chosen for a basic physical was at the Clinic's Independence Medical Center.

Ready for round two, I called the appointment line. Again ... no insurance? No appointment. This time, though, I was put on hold to speak with the Independence counselor. With the words Our mission is to provide a best-in-class patient experience repeating interminably on the other end of the line, I decided I was ready to give up best-in-class in exchange for a patient experience of any kind.

I hung up after 25 minutes, thankful for not having a real problem — say, a raging ear infection that could have morphed into blood poisoning and killed me before a live operator answered the phone.

Days later, I reached the second Clinic counselor — the one who helps with regular doctors. A routine physical would cost $346. Once again, discounts for the semi-impoverished were revealed only when I asked: That $346 would be discounted by 75 percent. She added a cryptic reference to "Obamacare" that would result in an even bigger discount.

Final score: A basic physical could be had for $44!

Within moments, I began debating whether to call back that first counselor to ask if she had an Obamacare special in her department too.

Shop Around

Cleveland Clinic is unique in that all of its doctors are employees of the system and cannot negotiate their own discounts. And "list prices" for those Clinic doctors are very high. Can the uninsured do better by negotiating with independent doctors who may have cheaper fees to start with?

A sampling of about 30 specialty and primary care doctors revealed that the next-best price for a basic physical was $75 (normally $150 when billed to insurance) at Westshore Primary Care in Westlake, a physicians group jointly owned by University and St. Vincent Charity. Important to note: This price applies to anyone without insurance, regardless of income. It's a great deal for those earning more than four times the poverty level and who either cannot afford insurance or are uninsurable because of preexisting conditions.

Other primary care practices — particularly those affiliated with University Hospitals' new Ahuja Medical Center — price physicals from $175 to $250 and offer no discount for the uninsured other than a standard 20 percent off if the bill is paid upfront. A number of independent doctors were slightly cheaper, but tended not to offer discounts at all — and none could beat that Clinic price of $44.

As for specialists? The type the Clinic wanted $519 for, University-affiliated practices priced at an average of $300. Again, none offered discounts for the uninsured except for the 20 percent off for paying at the time of the appointment. (One independent specialist in Middleburg Heights did make a concession for the uninsured, regardless of income: He asked for $100, but was willing to "work with" people even if they could pay only $10 a month.)

There are two other options well worth mentioning. MetroHealth offers physician visits for the uninsured at a total cost ranging from $5 to $30 for anyone in the county under the 400 percent poverty-level income limit. No surprise, considering the mission of the county-run facility is to ensure healthy residents.

What is surprising is what Parma Hospital offers for anyone working but without insurance, regardless of income: free appointments through its Parma Health Ministry. Flipping Whoppers at Burger King? Drawing $200K but can't get insurance? The line forms to the left.

The Painful Cost of Surgery

With my fuzzy vision growing worse, I set out to find a hospital that would cut a deal on the basic eye surgery I needed. I found an independent doctor I liked and had an exam ($148 with a 20 percent discount). He agreed to negotiate a surgery fee I could afford ($600) — but alas, he would be using a Clinic hospital: Lakewood. This meant a third Clinic financial counselor and another review.

I gave up on reaching Lakewood's counselor after a couple days of holding for a half-hour, being transfered to the main Clinic line, then back to Lakewood again.

It was time to switch gears to University, never mind that I would be obliged to find a different eye doctor who operates there. There was no financial review before being granted an appointment. Customer service was fantastic; indeed, failing health has never been so joyful. Although everyone was refreshingly helpful, a week passed before I learned how much it would actually cost.

And that cost was frightening: an incredible $9,000 for less than an hour in the operating room and a wafer of plastic to replace my pine-needled lens. What would I pay with my miserly income? $1,560. Not bad, and just one extra phone call yielded that price.

But Parma Hospital did better. One call yielded the "eye surgery package deal" of $1,100 — about a third of what would normally be billed to insurance. It was like a health-care happy meal. Plus, Parma's packages are good for anyone without insurance, regardless of income.

Working Out the Kinks

For those willing to shop around, there is a great deal of assistance available for the many uninsured who likely assume they don't qualify. The time drain, however, just might kill you.

It isn't supposed to be that way, says Clinic spokeswoman Eileen Sheil. And once connected with a counselor, you shouldn't have to ask for a discount. "Our financial counselors do so many things for these patients," she says. Among the Clinic's many little-known services: arranging for free groceries and paying COBRA insurance premiums for the unemployed who cannot afford them.

"I think the Clinic has come a long way in streamlining it," Sheil says. "We're so large and with so many independent hospitals [like Lakewood] recently coming into the system, it takes a while to work out."

Here's hoping they work it out soon. Compared to University, the Clinic offers much better discounts for the uninsured.

A survey of prices and discounts for independent hospitals Southwest and St. Vincent reveals that neither can compare to those offered by Parma. Spokesman Mark White chalks it up to a history of being careful with money because, as a small hospital, it doesn't have the volume that the large institutions see.

"We are dedicated to the health of the whole community, and that's how we operate," he says. "We don't just look for the best or highest-paying patients."

As for my woes? I've decided to stay with that Clinic specialist and primary care doctor. But I am now in the Clinic's computer system as a charity care patient and have to endure another round of phone calls to set the record straight. Meanwhile, my eyesight grows worse and my bones could disintegrate any day now. And I still don't have any appointments.