Angela Garcia's 2001 Arson, Murder Conviction Still Raising Questions. The Intercept Came to Cleveland to Investigate

By Eric Sandy on Mon, Mar 13, 2017 at 11:13 am

[

{

"name": "Ad - NativeInline - Injected",

"component": "38482495",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

},{

"name": "Real 1 Player (r2) - Inline",

"component": "38482494",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9"

}

]

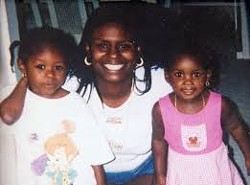

In a towering piece published last Sunday, The Intercept's Liliana Segura reports on the circuitous tale of how Angela Garcia was convicted of — and later pleaded guilty to — burning down her Cleveland home and killing her two young daughters. The story reveals deep truths about the criminal justice system in America and about the legacy of corruption and racial tension in Cleveland.

In 2001, Garcia was convicted of aggravated arson and murder during a third trial; a fire at her house on Harvard Avenue had killed her two young daughters in 1999. Later, during an evidentiary hearing in 2016, Garcia pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter as part of an unexpected plea deal. The case was riddled with prosecutorial holes, dubious judicial conduct and more questions than answers.

Prior to the Garcia story, Segura published a feature on the arson conviction of Claude Garrett in Tennessee. He was sentenced to life in prison for a fire that took place in 1992. "It was one of those stories, similar to Angela Garcia's story, where I started it a long time before I ended up publishing it," Segura tells Scene. "It was a long journey...and over the course of that reporting I just got really, really interested in the topic." She mentioned David Grann's rather emblematic 2009 story on a questionable arson conviction as a point of reportorial inspiration.

"I just kept thinking how many other people might be out there who are locked up on bad arson evidence," Segura says, citing also the role of insurance companies in developing some bad practices in arson investigation. (While insurance motives drew Segura to the case, that narrative didn't end up being a major aspect of her final story.)

Among the curious elements of Garcia's case (which Segura covers deftly), there is an array of junk arson science, long disputed and/or debunked; a network of snitches in Cuyahoga County, two of whom worked actively for Garcia's conviction, which one of whom later walked back privately; bait-and-switch techniques on the part of the prosecutor's office's narrative, helmed then by Bill Mason; an incredibly ill-informed judge in Judge Bridget McCafferty, whose law license was later suspended; and the long history of Cleveland's segregated neighborhoods bubbling to the surface in jury deliberations and subsequent media coverage.

In fact, on that last note, Segura works in a really terrific overview of Cleveland's history of racial tension. (Segura lives in Nashville; The Intercept is based in New York.) "I don't like parachuting into a place I don't know and drawing sweeping conclusions," she says. "I try to understand the place, to start, through its news coverage." Amanda Garrett's Plain Dealer stories on the original Garcia trials proved invaluable. Additional reporting from your humble alt-weekly — on Mason's rise to power, McCafferty's reputation, and the history of wrongful convictions in Cleveland — filled in the systemic gaps. She drove around Garcia's old neighborhood and caught herself up on development reports that drew a line from 1999 to the present on the city's eastside. (She also happened to be in town during the wake of the Tamir Rice shooting, which, readers will recall, had pushed Cleveland to an incredibly tense point in its history of police and community relations.)

Back to the matter at hand, though, Segura says that these arson cases are of such great interest primarily due to the scant evidence that is usually available. (The day after the Harvard Avenue fire, Garcia’s home was demolished.) Snitch testimony and prosecutors’ theories end up holding far more weight than they might in a criminal case with eyewitnesses, DNA evidence and sturdy public records.

Scene followed the Antun Lewis arson case over the past decade and reported on the role that snitch testimony played in his conviction — and in the granting of his second trial. A third trial was denied, but all along the local network of snitches was quietly pushing that criminal case forward. “The more people that understand that, the better it is for the system,” Segura says.

Former county prosecutor Timothy McGinty organized the Conviction Integrity Unit, which seeks to revisit potentially problematic convictions. Garcia's application was denied prior to last year's plea deal.

Read Segura's story, The Fire on Harvard Avenue, here.

In 2001, Garcia was convicted of aggravated arson and murder during a third trial; a fire at her house on Harvard Avenue had killed her two young daughters in 1999. Later, during an evidentiary hearing in 2016, Garcia pleaded guilty to involuntary manslaughter as part of an unexpected plea deal. The case was riddled with prosecutorial holes, dubious judicial conduct and more questions than answers.

Prior to the Garcia story, Segura published a feature on the arson conviction of Claude Garrett in Tennessee. He was sentenced to life in prison for a fire that took place in 1992. "It was one of those stories, similar to Angela Garcia's story, where I started it a long time before I ended up publishing it," Segura tells Scene. "It was a long journey...and over the course of that reporting I just got really, really interested in the topic." She mentioned David Grann's rather emblematic 2009 story on a questionable arson conviction as a point of reportorial inspiration.

"I just kept thinking how many other people might be out there who are locked up on bad arson evidence," Segura says, citing also the role of insurance companies in developing some bad practices in arson investigation. (While insurance motives drew Segura to the case, that narrative didn't end up being a major aspect of her final story.)

Among the curious elements of Garcia's case (which Segura covers deftly), there is an array of junk arson science, long disputed and/or debunked; a network of snitches in Cuyahoga County, two of whom worked actively for Garcia's conviction, which one of whom later walked back privately; bait-and-switch techniques on the part of the prosecutor's office's narrative, helmed then by Bill Mason; an incredibly ill-informed judge in Judge Bridget McCafferty, whose law license was later suspended; and the long history of Cleveland's segregated neighborhoods bubbling to the surface in jury deliberations and subsequent media coverage.

In fact, on that last note, Segura works in a really terrific overview of Cleveland's history of racial tension. (Segura lives in Nashville; The Intercept is based in New York.) "I don't like parachuting into a place I don't know and drawing sweeping conclusions," she says. "I try to understand the place, to start, through its news coverage." Amanda Garrett's Plain Dealer stories on the original Garcia trials proved invaluable. Additional reporting from your humble alt-weekly — on Mason's rise to power, McCafferty's reputation, and the history of wrongful convictions in Cleveland — filled in the systemic gaps. She drove around Garcia's old neighborhood and caught herself up on development reports that drew a line from 1999 to the present on the city's eastside. (She also happened to be in town during the wake of the Tamir Rice shooting, which, readers will recall, had pushed Cleveland to an incredibly tense point in its history of police and community relations.)

Back to the matter at hand, though, Segura says that these arson cases are of such great interest primarily due to the scant evidence that is usually available. (The day after the Harvard Avenue fire, Garcia’s home was demolished.) Snitch testimony and prosecutors’ theories end up holding far more weight than they might in a criminal case with eyewitnesses, DNA evidence and sturdy public records.

Scene followed the Antun Lewis arson case over the past decade and reported on the role that snitch testimony played in his conviction — and in the granting of his second trial. A third trial was denied, but all along the local network of snitches was quietly pushing that criminal case forward. “The more people that understand that, the better it is for the system,” Segura says.

Former county prosecutor Timothy McGinty organized the Conviction Integrity Unit, which seeks to revisit potentially problematic convictions. Garcia's application was denied prior to last year's plea deal.

Read Segura's story, The Fire on Harvard Avenue, here.

SCENE Supporters make it possible to tell the Cleveland stories you won’t find elsewhere.

Become a supporter today.

About The Author

Eric Sandy

Eric Sandy is an award-winning Cleveland-based journalist. For a while, he was the managing editor of Scene. He now contributes jam band features every now and then.

Scroll to read more Cleveland News articles

Newsletters

Join Cleveland Scene Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.