Cleveland Police Use of Force: Only 4% of Officers Reported Using Force More Than Three Times in a Year. This Officer Reported Seven.

By Cid Standifer on Fri, Oct 22, 2021 at 8:00 am

[

{

"name": "Ad - NativeInline - Injected",

"component": "38482495",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

},{

"name": "Real 1 Player (r2) - Inline",

"component": "38482494",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9"

}

]

On the Fourth of July in 2014, police responding to a call about gunshots chased someone into the middle of a child’s backyard birthday party. After a scuffle, the man was brought to the ground and handcuffed. Officer Ryan Sowders crouched on his back, while another officer held the man’s feet. Then, Sowders punched the man in the head.

Sowders eventually faced a misdemeanor assault charge for the punch, which the court deemed excessive and not covered by “qualified immunity.” He was convicted in 2017, and lost an appeal in 2018. He ultimately paid a fine of $869. The department also suspended him for 30 days.

But the conviction didn’t end Sowders’ time in the Cleveland Police Department, or deter him from using force. In fact, in 2019 and 2020, Sowders filed more use of force reports than any other officer in the department, according to police department data obtained by Scene through a lawsuit.

Sowders’ continued use of force, and the city’s resistance to releasing information about it, raises questions about whether policies and reporting requirements created under its consent decree with the Justice Department actually create transparency, or lead officers to change their behavior.

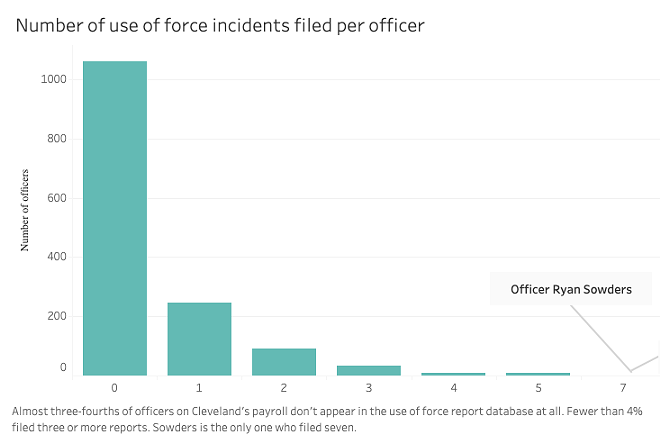

Almost three-quarters of the officers on the city’s payroll filed no use of force reports at all over that period. Another 17% filed one report. Fewer than 4% of officers filed three or more use of force reports. Sowders filed seven.

Stephanie Kent, a sociology professor at Cleveland State University who studies the justice system, said an unusually high number of use of force reports by a single officer should raise alarm with their superiors.

“These are the kinds of things that should be tracked. If somebody is a hothead, or is more likely to be violent, then they can find out why,” she said.

But Jeff Follmer, president of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, said a high number of use of force reports alone shouldn’t be held against an officer.

“We don’t pick and choose when and where we have to use force,” he said. Follmer also suggested that some actions classified as use of force, like bringing down a suspect who tries to flee when already in handcuffs, shouldn’t be considered use of force, and generate too much paperwork.

Every one of Sowders’ use of force reports was declared within department policy.

Police department policy doesn’t require an officer to be terminated for committing a crime unless the conviction prevents them from carrying a gun, such as in domestic violence cases. “Minor misdemeanor” convictions are placed under the lowest level of disciplinary infractions, but since Sowders’ fine was over $150, Ohio law wouldn’t classify it as “minor.”

Jeff Follmer, president of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, said it’s not unusual for officers to stay on the force after being convicted of a crime while on duty.

“We’ve had officers convicted of misdemeanors numerous times,” he added.

No resistance

Five of the reports said Sowders pointed his weapon at someone. Under Cleveland department policy, that’s considered a level 1 use of force, which is the least serious.

In one instance in November 2019, Sowders was one of several officers who reported pointing their weapons at a man using his children as hostages. In other instances, though, the subject didn’t seem to pose an immediate threat.

Sowders said in one use of force report he pointed a gun at someone who kept walking away when officers told him to stop. Sowders wrote in his report that he thought the man had a gun, but later found it was a cell phone. The man reportedly told officers later that he had been hoping they would shoot him. Under the level of resistance involved, Sowders categorized the incident as “active resistance.”

The body camera footage provided by the department shows Sowders getting out of a vehicle and shouting “Put your hands up” at a man in a gray hoodie who is standing still, staring open-mouthed at the police, already holding his hands up and out at shoulder height with bent elbows.

“Put ‘em up! All the way up in the air!” Sowders can be heard yelling at the man, who remains motionless. “You don’t listen very well,” he adds as they pull the man’s hands down and handcuff him.

“I wouldn’t hurt y’all,” the man says. “I didn’t hurt nobody. I didn’t do nothin’ out of spite, right? Right? I ain’t do nothin’ out of spite.” He adds that he’s been drinking. He begins to drop to his knees, but Sowders tells him to stand back up. As police walk him toward a cruiser, the man can be heard weeping.

Sowders says the man is going to give him a hernia by “dropping like a dead weight.”

“I don’t want to give you a hernia,” the man sobs.

In another incident, after pulling over a man who matched the description of a homicide suspect, Sowders pointed his gun at him while he “gave no resistance and exited the vehicle” following another officer’s directions, according to the use of force report. Another officer filed a use of force report saying he also pointed a gun at the subject.

The body cam video confirms the officers’ description of events. In the video, after reading the man his Miranda rights, Sowders asks his name.

The man’s ID verifies that he’s not the person the police are looking for.

“The guy we’re looking for, that’s involved in a homicide, has just as many face tattoos as you,” Sowders tells him.

“Yeah, I saw him on Facebook,” the man says. “That’s not me, sir.”

Punches and tasers

Reports where Sowders said he used higher levels of force include one where he punched someone who was resisting arrest; and one where he tased someone who was wrestling with other officers.

A video of the first incident shows Sowders arriving when the subject is already restrained, but appears to try to squirm away from a security guard. The man can be seen banging his own head against the hood of the squad car, and then against the concrete.

Multiple officers end up holding him on the ground. One says, “Stop it man, all you are is drunk.” A woman asks him, “Why do you want to hurt yourself?”

When Sowders empties the man’s pockets and finds what appears to be drug paraphernalia, the man becomes more and more agitated, encouraging the cops to choke him and pull out their guns. At one point he shouts, “I want to die! I will! Tonight!”

Through much of the video, the camera lens appears to be covered as Sowders wrangles with the subject. It’s not clear when Sowders struck him, or when the subject bit Sowders, as he wrote in his report.

In a March 2020 incident, Sowders arrives at the scene of a call about a break-in when multiple officers are trying to restrain a young man on the pavement.

“Are we tasing?” Sowders asks.

“No,” one of the officers says.

But when the struggle continues for a few more seconds, Sowders says, “Stop resisting,” and points his taser at the man’s exposed belly.

“You’re going to get tased! Do you understand?” another officer shouts at the young man.

Sowders orders him to turn over. When he doesn’t, Sowders tases him.

After handcuffing him, the officers carry the man to the squad car while he screams “Buba! Buba!”

Then the officers ask if he speaks Spanish.

“I am Nepali,” he says. “My father this he home.”

“Buba” is Nepali for “father.”

The young man’s age isn’t listed in the report, but Sowders estimated he was 125 pounds and under 5 feet tall. A use of force report filed by another officer for the same incident said they had guessed early on that the subject didn’t speak English because he wasn’t responding to any of their commands.

The consent decree between the Justice Department and the Cleveland Police Department requires that officers be “trained to consider the possibility that a subject may be noncompliant due to a medical or mental condition, physical or hearing impairment, language barrier, drug interaction or emotional crisis.”

“There’s four officers there,” Kent said after watching the video. “Why couldn’t there be some way for them to take him down or restrain him without having to resort to the taser?...He’s not a physical threat, and he can’t speak the language. I just don’t understand why the taser needed to be deployed.”

On the other hand, she said, police have few resources to deal with people who can’t communicate.

“[Police are] not trained social workers. They’re not trained psychologists. They’re not trained linguists,” she said. “They basically go on what procedure is used in any other incident, regardless of whether the other person is under the influence or not speaking English or has a mental illness.”

Delays and redactions

Some of the videos provided by the department don’t show the moment Sowders says he used force.

One man, at whom Sowders pointed his gun on April 17, 2019, was reportedly hiding in a basement with a lampshade on his head. The video goes black, containing only audio, at the moment Sowders starts to enter the lighted basement.

In another report, the subject was coming down the stairs toward Sowders after failing to find an exit where he could escape. Most of the picture is blurred out when Sowders approaches the door of the house, and it’s impossible to tell what the subject was doing as Sowders yelled at him to put his hands up.

Other discipline

Individual uses of force are supposed to be reviewed to make sure they fall within department policy. Follmer added that there is a review process for officers whose statistics fall outside the norm, but it includes other factors, like excessive sick days, not just use of force reports.

But Sowders has been in trouble for other incidents. In fact, he was disciplined in his first year on the force. In Sept., 2013, he crashed into a woman’s car on Lorain Ave. while responding to a call. The woman sued the department. The judge decided Sowders had immunity because he was responding to a call at the time, but the department suspended him for one day for driving too fast. The next year he was suspended again, this time for five days, for being involved in a hit-skip accident.

More recently, Sowders was suspended for one day in 2019 for an unspecified violation involving his body camera, according to the department’s periodic discipline announcement from that April.

Then, in July 2020, the Civilian Police Review Board decided that Sowders had behaved unprofessionally after an incident at Old Angle Boxing Gym where a sparring match devolved into a brawl. Sowders told the father of a 14-year-old, who had been sparring a 28-year-old, that he’d made a “mistake” by allowing his son to spar with an adult, and should be charged with assault for intervening.

He was given a formal reprimand for the incident in January 2021, though the department listed under “mitigating factors” that his “advice given was out of concern for the wellbeing of the juvenile without intent to be discourteous or rude.”

While Sowders’ filed more use of force reports than any of his colleagues in 2019 and 2020, his numbers were far lower than the most prolific filers of force reports in 2010, according to a Plain Dealer analysis from a decade ago. In 2010, the paper reported, 11 officers filed eight or more use of force reports. Two of those officers were charged in 2011 for beating a mentally ill man after a police chase, leaving him with a broken eye socket and detached retina.

In February, Williams pointed out that the department’s total number of use of force reports have been on the decline. Under the consent decree, he said, training has been instituted to ensure that officers know how to use force in a way that is constitutional.

“And, as occasionally happens when officers don’t maintain that standard they’re held accountable,” he said.

“The use of force is part of the role of policing. It’s part of what we ask officers to do. We just ask them to do it thoughtfully and judiciously,” added Brian Maxey, a deputy monitor on the Cleveland Police Monitoring Team. “Do they have the least reliance on the use of force as a tool when engaging with community members? That’s the litmus test, not just the numbers.”

SCENE Supporters make it possible to tell the Cleveland stories you won’t find elsewhere.

Become a supporter today.

Scroll to read more Cleveland News articles

Newsletters

Join Cleveland Scene Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.